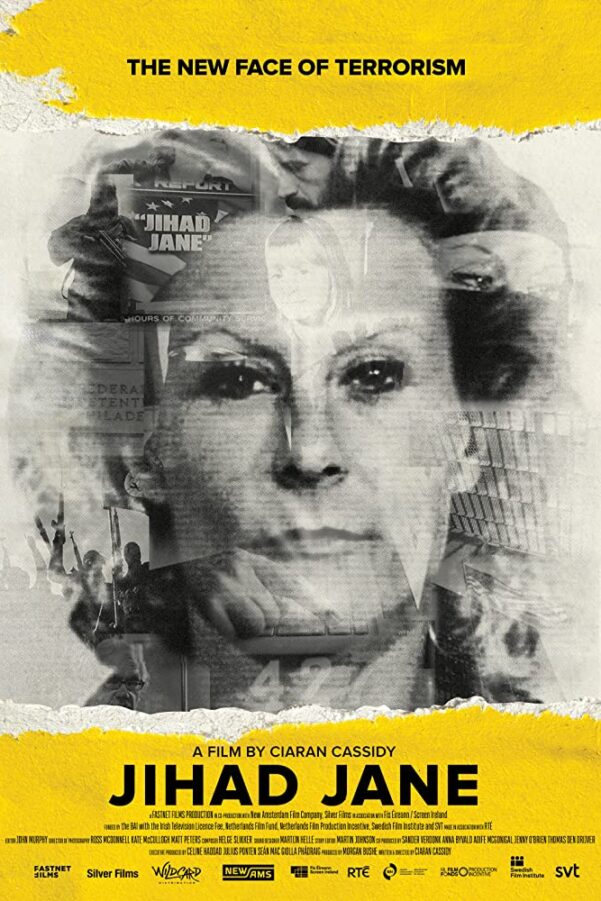

Jihad Jane

In March 2010, the Washington Post ran the headline: “‘Jihad Jane’, a new kind of threat”. It joined the growing US media frenzy over a white, blonde-haired, blue-eyed woman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania called Colleen LaRose. In 2008, LaRose had converted to Islam, taken up the moniker “Jihad Jane” online, and then left America to prepare to answer a fatwa against controversial Swedish artist Lars Vilks. When LaRose eventually handed herself in to US federal authorities after the “mission” hit a dead end in Waterford, Ireland, she never realised she’d become the “new threat” in America’s domestic war on terror.

Ten years on, director Ciaran Cassidy attempts to go behind the “new faces of terrorism”, also covering the connected case of Jamie Paulin-Ramirez (given the name “Jihad Jamie” by the media). Utilising both formal and informal interviews with the two women, their families and defence attorneys, Cassidy tries to provide intimacy with the causes, actions and consequences of these cases.

The director’s pared-down style and John Murphy’s sensitive editing is often juxtaposed with the news media’s loud hysterics and racist profiling in coverage at the time. Ross McDonnell’s cinematography (evocative wide, brooding landscapes or small details of economic hardship) might be typical of the aesthetic popularised by Netflix’s Making A Murderer, but it lets the detail sink in and its subjects’ conflicted feelings percolate.

Outside the composed interview backdrops, Cassidy pushes his hand-held camera into close proximity. The director captures quiet, candid moments rife with unresolved tensions and contradictions. Witnessing the impact of the women’s decision on their families or partners, especially Paulin-Ramirez’s mother, stepfather and teenage son, is a particularly difficult, raw watch. It is clear that trying to build a future after these events is by no means assured, despite the two renouncing terrorism and serving jail time. The pain they cause reverberates sharply in the present. There are also shades of nuance given to others in this case: Mohammed Khalid Hassan (dubbed “America’s youngest jihadist”), Jane’s co-conspirator, is presented as a victim of social isolation, while Vilks comes across as an aloof, clumsy provocateur.

Cassidy’s most salient insight comes from the psychological trauma in the women’s respective backgrounds. The documentary strongly implies that the women’s personal histories of emotional and sexual abuse, leading to a desperate desire for recognition, dependency and belonging, seeded their susceptibility to exploitation online. In doing so, the director moves away from any narrative of religion and ideology as the primary cause of radicalisation. As LaRose baldly states to leave the viewer in no doubt of her actions: “Islam didn’t do this to me – I did this to me.”

But Cassidy isn’t letting LaRose or Paulin-Ramirez bear all the responsibility. Instead, Jihad Jane probes further than the sensationalistic headlines or even the incongruent, ambivalent remarks of its subjects (“Now, I’m somebody. I’m Jihad Jane, I’m somebody,” LaRose proclaims, while also saying she’d vote for Trump) to thoughtful effect.

James Humphrey

Jihad Jane is released digitally on demand on 11th May 2020.

Watch the trailer for Jihad Jane here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS