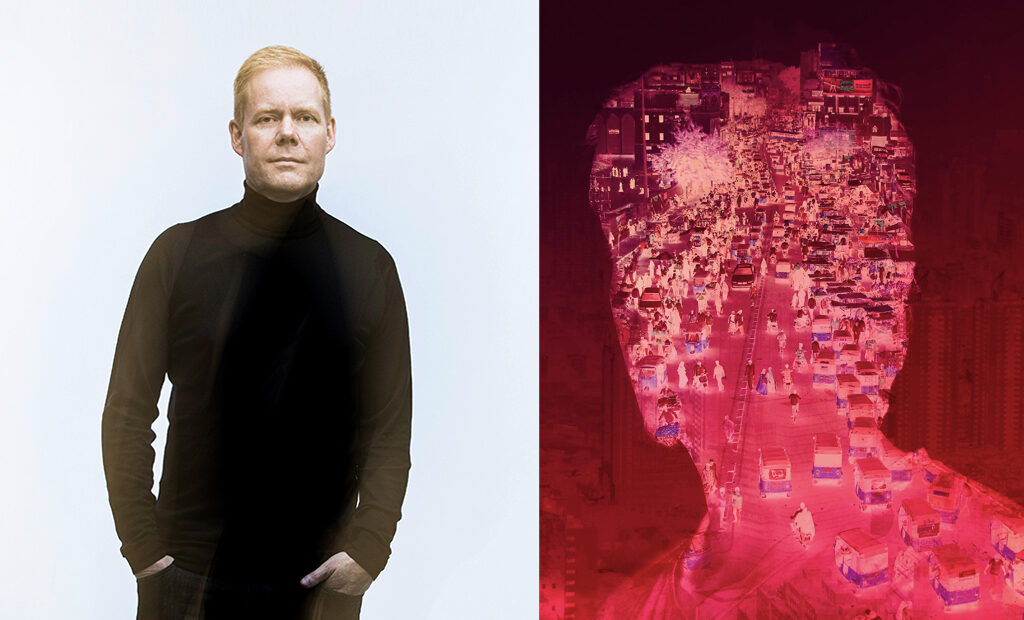

Max Richter on Voices: “I wanted to make a piece about human rights because their erosion is unfortunately always relevant”

Voices is the latest work from experimental classical composer Max Richter. Based around the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it premiered last February at the Barbican. Voices is distinguished by the alternation between selected articles narrated by Kiki Layne and musical works ranging from minimalist piano pieces to ethereal electronic soundscapes.

This ambitious project – ten years in the making – aims at highlighting the value of a global community by utilising crowd-sourced recordings: hundreds of submissions in over 70 languages. It also features an “upside-down” orchestra, where the low frequencies of cellos and double basses dominate over the conventional prevalence of violins, violas and woodwind.

We spoke with Richter about the writing process behind this work, the comparison with scoring a film and the music he enjoys listening to that no one would suspect.

It’s a sad week to do this interview because of the passing of one of the greatest music composers of our time, Ennio Morricone. What was your reaction to this and what was the impact on your music?

Yeah well, it’s very sad; he was a composer whose work in cinema really elevated the genre and transcended it in a way which very very few other composers managed to do. I think that’s because his work was much broader than just the cinema: he worked with all sorts of experimental music and technology, especially in the 60s. He was a brilliantly able musician in many departments. He did all of his orchestrations, for example, which is very unusual in cinema. An extremely gifted and wide-ranging artist, his own work had a tremendous emotional directness – and obviously he was a fantastic melodist. He was the real thing, right? Rest in peace.

He lived quite a happy and long life, bless him.

Yeah, 91!

I was at the premiere of Voices at the Barbican, the first night, and I found it quite impressive. Obviously – and sadly – a work based around the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is always relevant, but did you expect it to become so current while you were working on it? I’m referring to the BLM protests and the discussion about our society’s ties to slavery.

Sadly, the subject of rights and the abuses of human rights is always relevant. And of course, right now the BLM response to systematic – by design – human rights abuses against a huge section of humanity over hundreds of years is very much in the forefront. Voices was written before this latest erosion of rights but yes, you are right, it is unfortunately always relevant, which is in a way why I wanted to make the piece.

Do you think it’s a political statement from you?

I don’t think it’s political; the declaration is universal. It was adopted almost universally, with a couple of abstentions here and there, but it was something that was agreed on and if you take away the political dimension and read that text as a human being, most people would agree with it. It just makes sense. It obviously has its origins in the time of World War II, so it’s written in response to chaos really, an antidote to chaos in a way, and I think it’s a very inspiring one.

How did the Barbican premiere help you finalise Voices and did you make any changes after that?

I made a few changes in rehearsals but not big changes. I spent so long working on the piece; it began roughly ten years ago so I felt like I kind of knew what I wanted to do with it. A performance is, in a way, a testing of a theory. You have a theory, which is your score, and you see if it flies and what happens when you play it. I think we felt really happy that it was working in the way I had intended it.

Testing moments with the orchestra never prompt you to make a change?

The score is the score and that’s what I’m all about really: the notes on the page; if I can get those notes right. Every performance has its own dynamics and in a way, a performance is a laboratory, a real-time experiment with a community of players and listeners. But I don’t change the score – we might emphasise slightly different things depending on the context of the show and every performance is different, but the notes are the notes.

Was it recorded shortly after the Barbican?

We recorded it straight away actually. It was about a week later, around a week before lockdown in the UK, so we were very lucky to get it recorded at all.

Voices is quite a journey, similarly to Three Worlds. It took me a while to digest and navigate through it. Some of the tracks are richer, some more minimalist. Considering it doesn’t exactly follow the order of the articles, how did you come up with it?

I couldn’t include the whole of the declaration as there’s a lot of it. So I tried to choose the sections which were the most plain-spoken, the most direct statements. That was the first thing: to adapt the text a little bit. And then there are some sections that I’ve repeated; I’ve repeated the first article a couple of times just because it’s really about the fundamentals, and I wanted to make sure that we all remember that. The structure of the record is really: you’re given a text and then you’re given a musical space to think about the text. And this is the alternation: text / music / text / music. That’s the basic structure of it so the music acts as a place to think, essentially.

I noticed that some of the language was revised. For instance, “brotherhood” has become “community”. How did you decide on these changes?

The declaration was written in 1948, but this is 2020 so I wanted a more gender-neutral word. Not brotherhood or sisterhood but community. It conveys the same thing in a more neutral way. Later on, there is an article to do with marriage and the original text says “men and women have the right to marry” and I thought, yes, that’s right, and arguably that’s still ok, because it doesn’t say marry each other or only each other, but I felt that our definition of what marriage is has become enlarged and more inclusive so I thought I’ll put everyone there because actually most of the articles start with “everyone”. So just the tiny adaptations, it’s not like I’m rewriting the UN declaration but I felt that, since it isn’t the whole text, and it is adapted, then I’ll use just a few tiny things to make it feel more in tune with where we are now rather than 1948.

Was it a light decision to make?

Light and not light. I can’t control what people will think about a project. The only thing I can control is what I put into the project; everything else is beyond my control so I have to do the best I can and be comfortable with what’s on the record and then after that, I’ll take my chances.

Were you worried about spoken parts, especially those within being disruptive for someone listening to the work?

Yes, in a way. I felt that this is at the heart of the piece and this is why the piece in a way exists so it has to be there. On the other hand, I understand that people might not always want to have the text so we’ve actually made music-only versions, which are another way to experience that landscape and the material. I’m actually quite interested in people navigating their own way through a piece. There’s something quite democratic about that: it’s presenting the material in an open form. I like that.

So when it’s released there will be two versions.

Yes, two CDs.

About the titles: I found some of the choices quite interesting, especially Mercy, the final one. Can you tell me how that came about?

Mercy is the last track on the record. It’s the first piece I wrote in 2010 and the impetus for writing was the events of Guantanamo, when the CIA memos were published and there was a feeling we had lost something fundamental in our civilisation, that this was a new kind of abuse, in a way. So I wrote Mercy as a space to figure that out for myself. The title comes from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, where Portia is talking to Shylock, and she gives this beautiful speech about the qualities of mercy – “The quality of mercy is not strained, it droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven, upon the place beneath” – and how it benefits both the person who is receiving it and the person who is being merciful. And I think that’s a beautiful image, a wonderful balancing force. So that struck me as a good image to build the piece around. The music of Mercy has been the kind of guiding principle for the whole of the project.

So you said Mercy was the first one, which one was the last one?

I don’t know actually. Like every project, the music that is on the record is like when you have an iceberg in the sea, you have a tiny bit showing and all the big rest is underneath. A record is like that. You have the bit on the record and then an enormous amount of music which isn’t on there because it didn’t fit in some way to the work. And my writing process is very much like that: I’m always making things and trying to fit them together and if they don’t fit together then it doesn’t happen. I actually don’t know, I just kept making and then I tried to put it together in a shape that worked.

How do you suggest we listen to Voices?

I think people have to find their own way. If they can find a way that the music fits into their lives, whether that’s listening through with the texts or without the texts. I think the texts are an important part of it; they are the sort of spine of the piece, the reason it exists. But then there are versions without the text, so I think you make your own way.

Am I right to understand there will be also a visual version of the work?

Actually, the project was always intended to be music and visuals, and Yulia [Mahr] and I have been talking about it for a long time, making this project as a kind of visual album. Even at the Barbican, we’d originally intended that there would be a music and film performance, that they would be one object. But I didn’t get the music together in time; it’s wasn’t happening and the date was getting closer. So we said we’ll do it one step at a time, we’re going to play the music, start there and then grow the film work into this composite as we go along through the performances. And now, of course, everything has been cancelled in the last few months and we don’t know when we’ll play it again. Yulia has started to release some of her film work for the project; we had the first video for All Human Beings and there’s another video for Mercy, so it’s kind of a glimpse into the bigger piece that’s still to come.

How does your approach to writing music change when you are scoring a film and the visual part is already done?

Scoring a film is completely different. Completely different. If you’re making a record or writing a concert piece that’s it: there are no parameters or limitations; you just do what you want to be doing. Whereas a film is a team effort, a collective effort, and you’re serving a story; the music is one element in a compositive storytelling mechanism with cinematography, acting, editing, the director. The dynamics are very different. A film score is not a symphony; it’s part of something, it’s not the whole thing, so it’s very conversational, it’s a collaborative process which I really like, but it’s very different to, say, writing a record.

Do you ever accept to write a score as a challenge, because it would take you to places where you wouldn’t normally go?

I guess so, in some ways. Every score is a challenge as you are trying to discover the music which feels native or inevitable in that imaginary world that the film occupies. It’s a process of discovery really: what are the things that feel like to belong in that universe? And that could be anything really – literally. So you never know.

Let’s take Ad Astra – which I really loved. What did the outer space setting allow you to do?

James [Gray] is a great, great filmmaker and Ad Astra was a wonderful project, and that allowed me to do things you would never get to do normally. The story of the movie is about Brad [Pitt]’s character going from Earth to Neptune, so thinking about the way the music would work I decided quite early on that I was going to use that journey. Because the Voyager probes already made that journey, so I contacted the University of Iowa Plasma Physics lab, who are in touch with the satellites, and I got all the data. The probes transmitted electromagnetic data back every nine seconds all the way, so there are all these data slices of their journey. The data allowed us to make a computer-modelled instrument out of this data. So that means that when Brad is flying past Jupiter, the music you are hearing is made from data from Jupiter. And that’s an amazing thing that could only happen in a movie project, because it only makes sense in a movie project. So the score, as well as being an illustrative and traditional film score, is also a document of the journey, which is a wonderful thing. It was a gift for music that movie.

How do you listen to music?

It’s a real mix. The first thing I do in the morning when I come downstairs is put on the radio on, which is Radio 3, a classical, experimental music station. So that’s basically on from the moment I wake up until I go to bed. In the kitchen, music is always playing and I like it as I don’t know what it is a lot of the time; I walk in, make a cup of tea and think “what is that?”, and then you listen for a moment and go and do something else. And I play records; it’s fun and records are great as they are 20-25 minutes and you can listen and then someone will stand up and put a new one on.

Is that your go-to piece of equipment?

I like vinyl. I like the sound of it, the feel of it; it’s nice.

On a fun note, is there a song that you really like that no one would expect you to listen to?

That’s an interesting one. I listen to a lot of stuff. I’ve been going through the early Chic records recently – Nile Rodgers records – and they are amazing. They are so beautifully made, and the playing on them is so incredible, so I guess, early disco, which is great. Chic are a treasure to the world.

Thank you very much for your time and congratulations again.

Thanks!

Filippo L’Astorina, the Editor

Voices is released on 31st July 2020 on Decca Records and available online as well as in store. For further information visit Max Richter’s website here.

Watch three videos from Voices here:

All Human Beings

Mercy

Origins

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS