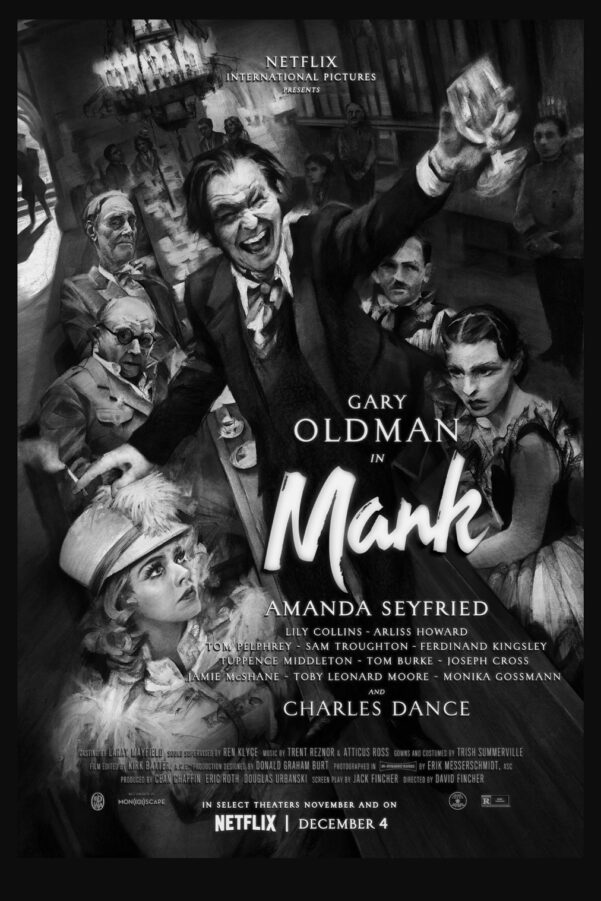

Mank

In Mank, David Fincher directs his careful authorial eye towards 1930s California, providing arguably the sharpest, warmest and, at times, brutally frank depiction of an era questionably famed as a “golden age” for the movie industry, even when most involved weren’t having a luxurious time. Take the case of Herman “Mank” Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman), a washed-up screenwriter who’s toiled through the sleaziness behind the scenes to write prodigy Orson Welles’s directorial debut Citizen Kane.

Cut off from his chief distraction in a “dry” cabin (where intoxicants still manage to get him into trouble), Mank struggles through Hollywood politics and an incapacitating leg injury to complete the mammoth screenplay, before braving the ultimate fight to get his name on the acknowledgements, sharing credit with a hubris-stricken Welles.

While this conflict is definitely the culmination of the film, the narrative is vastly more detailed than a simple “Mank versus Welles” story-arc. Through cross-cutting flashbacks, we observe the titular writer’s tumultuous adventures at Paramount, meeting, dealing, fighting and preaching to some of the movie capital’s giants – chiefly MGM head Louis B Mayer (Arliss Howard), director William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried) – who supposedly paved the way in Mank’s drunken but astute mind for Kane‘s centrepiece characters.

Alcohol, deaths and political propaganda all compromise the screenwriter’s life – made worse by the fact that he is constantly struggling uphill, the diligent cog in a soulless blockbuster machine that ultimately both defeats and submits to him.

The combination of Fincher and Oldman’s talents is what sells the depth and duality of Mank. The latter may be on the verge of slipping into his English accent every so often, but his perpetually slurred cadence juxtaposed with the odd esoteric reference is a true delight – and sometimes hilarious. The feature is cast perfectly, with Howard and Seyfried among the standouts, but Fincher outdoes himself with the level of visual and historic detail, pinning down the hard facts along with his own romanticism for the era.

Although never a complimentary fabrication, the Hollywood of the work is partially a whimsical fantasy; everything is perfectly crafted as we’d expect it, down to the quick-talking trans-Atlantic speak, the jaunty hustle of sound stages and even a practical joke left by the Marx Brothers. Retro technical details like pops in the dialogue and cue marks help uphold the dreamlike vision that’s unfolding, while pristine digital imagery simultaneously hints at Fincher’s inclination for transparency and revisionism.

Despite this desire for truth, it should be comforting for Welles purists that his genius is not insultingly downplayed in favour of the eponymous figure. How many of Mank’s ideas survive in Kane’s final cut is not spelt out, nor is that the point of the story. This succinct tale on Tinseltown’s working writers – of an intelligent man turning Hollywood rigidity on its head – is long overdue. Even if it’s acknowledged that Citizen Kane wasn’t one of the tidiest films ever, there’s a chance that Mank might claim this title.

Ben Aldis

Mank is released on Netflix on 4th December 2020.

Watch the trailer for Mank here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS