Ten artistic depictions of the Christmas story through the ages

After the challenges of this most difficult of years, many of us are looking forward to Christmas even more than usual, albeit a considerably less sociable one. During this turbulent time, art’s most memorable depictions of Christmas can uplift our spirits and renew our hopes for the restoration of normality. The Christian story has been inspiring artists for centuries. Here is a festive sprinkling of ten of the most celebrated and impactful works.

Raphael, The Sistine Madonna (1512)

Commissioned in 1512 by Pope Julius II, The Sistine Madonna is a masterpiece of the High Renaissance. Originally installed on the high altar of the Benedictine abbey church of San Sisto in Piacenza, it now resides at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Gallery) in Dresden, Germany. Raphael has created a harmoniously balanced design, deploying clever illusionism to convince the viewer that the painting is a stage. At the top, the Madonna is holding the infant Christ. Lower down to the left, Saint Sixtus looks up to her while gesturing outward to the worshippers viewing the image from beyond the canvas. Opposite stands Saint Barbara, whose relics were held in the church of San Sisto. The three main figures are positioned in an imaginary space framed by green curtains looking down upon the church faithful from the clouds. At the bottom of the composition, two impish cherubs rest their elbows on the curtain and rod that frame the painting, gazing up at the figures above them.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Census of Bethlehem (1566)

Image: Bridgeman Art Library / Royal Musuems of Fine Arts of Belgium

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Census of Bethlehem offers a spotlight on the extreme hardships suffered by the population of the Netherlands and large parts of Europe during the previous year’s savagely cold winter. Rather than attempting to imitate the topographical features of Bethlehem, Bruegel posits the central characters of a pregnant Mary and Joseph in his Flemish homeland. We are presented with an elevated view of a scene teeming with life as Joseph leads a donkey riding Mary to a crowded inn. This artist’s “all prima” technique of producing light effects though the layering of still wet applications of paint and impasto brush strokes is much in evidence here. The painting is on display at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, a city where Bruegel lived from 1563.

Caravaggio, Nativity with St Francis and St Lawrence (1609)

In this exceptional work by Caravaggio, the master of chiaroscuro, the artist positions the infant Christ centrally, lying on a bed of straw in the stable. A multitude of saints and shepherds have assembled to pay homage to the newborn saviour. At the top of the painting, an angel is depicted carrying a banner that reads “Gloria”. The angel’s other hand points to the heavens as if to confirm the child to be the son of God. Originally commissioned in 1609, the painting hung above the altar at the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, in Palermo, Sicily until it was stolen on October 18, 1969. Its fate remains a mystery.

El Greco, The Adoration of the Shepherds (1612-14)

El Greco’s The Adoration of the Shepherds was completed in the final year of the artist’s life. His intention was for a version of it to be hung in his family tomb. El Greco pours all of his religious intensity into the canvas, his characteristically elongated figures twisting and contorted. The artist’s use of vivid reds, blues, yellows and greens in the clothing creates a dramatic contrast with the dark edges of the painting. Angels gather above, their bodies foreshortened. There’s a tremendous sense of movement with every figure coming together around the Christ-child who bathes them in his divine light.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Adoration of the Magi (1633-34)

Anyone who has watched the annual BBC coverage of the choir of King’s College, Cambridge’s nine lessons and carols concert will be aware of Peter Paul Rubens’s magnificent painting, The Adoration of the Magi, above the chapel’s altar. The Flemish baroque master unleashes all of his characteristic flamboyance into this Counter-Reformation masterpiece, imbuing the biblical scene with movement and brilliant colour. The three magi are depicted full-length, the eldest kneeling to kiss the foot of the infant Christ. As he does so, the Child, urged forward by the Virgin Mary, appears to offer a blessing with his right hand.

John Leech, The Second of Three Spirits or Scrooge’s Third Visitor (1843)

It has been claimed that Charles Dickens can be said to have invented the modern idea of Christmas. Anyone reaching such a conclusion could not fail to acknowledge the contribution of the artist responsible for the illustrations of the first edition of A Christmas Carol, John Leech. His vivid depictions of the author’s miserly Ebenezer Scrooge and long-suffering Bob Cratchit and his family further planted the seed in the minds of the British public that it was wrong to work on Christmas Day – in time leading to the Bank Holidays Act. In Leech’s The Second of Three Spirits we see Scrooge visited in his dream vision by the genial, torch-holding Ghost of Christmas Present. He reminds Scrooge of the joys of the season, the floor and room filled with an abundance of food and greenery, a roaring fire bringing warmth to a formerly cold house.

Paul Gauguin, Bébé (Nativity) (1896)

The usual interpretation to Gauguin’s Bébé (Nativity) painting of 1896 is that the artist’s teenage Polynesian mistress, Pahura, gave birth in December of that year to a baby girl, who tragically died weeks later. However, there is an alternative theory that Gauguin simply decided to paint an unorthodox version of the Madonna to challenge religious doctrine. Many of his works contain Christian symbolism, as well as references to Tahitian religion. The artist had sought out a new life in what was then French Polynesia to escape the conventions and demands of the western “civilised” world and in this spirit, the painting would seem to have two nativities. The figures in the bottom right are looking at the woman on the other side of the stable, the latter having been given a halo. Gauguin intentionally focuses on the newly born Tahitian baby rather than the child that is about to be born.

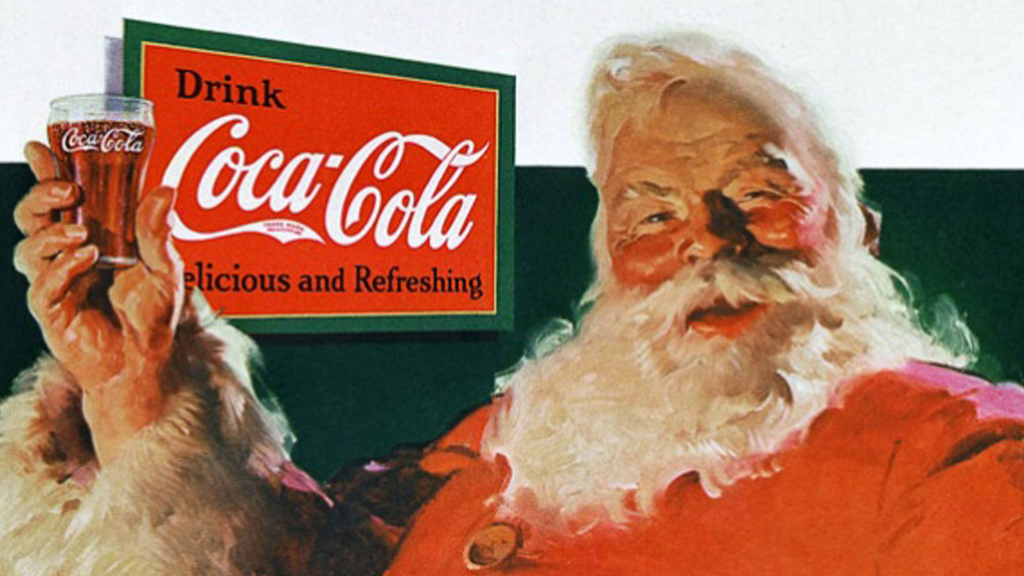

Haddon Sundblom, The first Coca-Cola Christmas poster (1931)

In 1931, Coca-Cola commissioned the illustrator Haddon Haddon to illustrate their first Christmas poster. It is believed he was paid the princely sum of $1,000 per painting. Sundblom channelled the sentiments he found in Clement Clark Moore’s 1822 poem A Visit From St. Nicholas (better known as Twas the Night Before Christmas) and gave pictorial form to Moore’s description of Father Christmas as a friendly, rather plump and merry gentleman. “My Hat’s Off to the pause that refreshes” was the slogan on Sundblom’s iconic first depiction of the Coca-Cola Santa. It appeared in The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s in December 1931 to remind people that Coke could be consumed all year round. Unfortunately, the original painting no longer exists, the price of canvas leading to the illustrator painting a new jolly Saint Nick over the top.

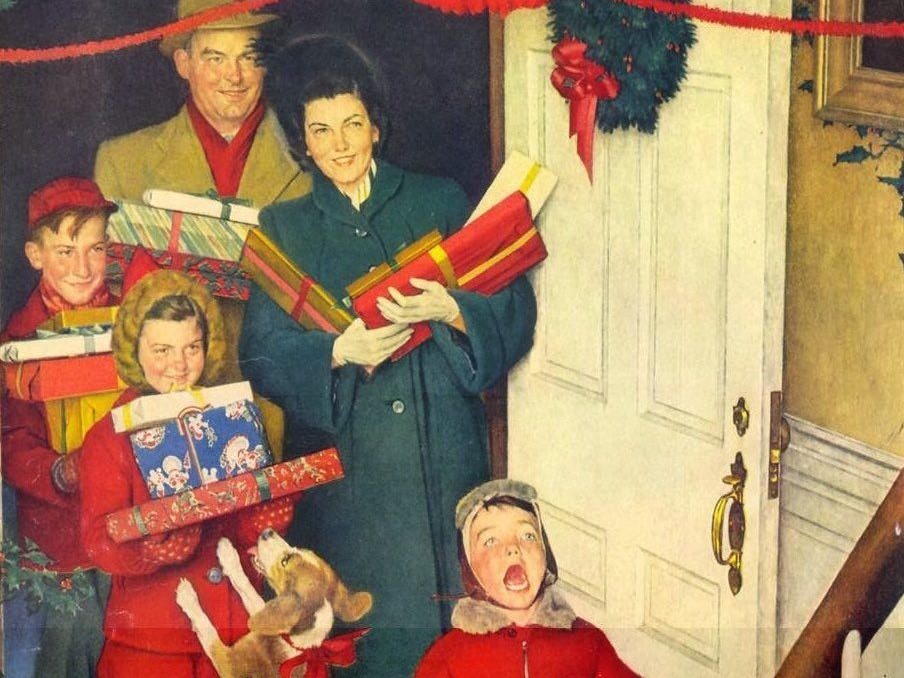

Norman Rockwell, Merry Christmas Grandma…We Came in our New Plymouth (Life Magazine) (1950)

Over the course of his near 50 years with The Saturday Evening Post, Norman Rockwell created 321 cover images, many featuring Christmas as their subject. They have been criticised for conjuring up a sugar-coated, sentimentalised America, far removed from reality, and yet they possess an undeniable charm. Rockwell also brought his particular idealised vision to Life magazine in the form of an advert for Plymouth cars. Here we see a picture-perfect American family, rosy-cheeked and laden with presents, entering the house of the childrens’ grandmother. The youngest child stands at the foot of the stairs and proudly yells up that they have arrived in their brand new Plymouth.

Henri Matisse, Nuit de Noël (Christmas Eve) 1952

Image: 2020 Succession H Matisse/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In January 1952, modernist master Henri Matisse was commissioned by Life magazine to create a window for end-of-year celebrations at the Rockefeller Center. The Frenchman produced a maquette of cut-and-pasted paper for the spectacular work, the composition featuring a large star in a Christmas sky over a landscape consisting of organic forms. On 8th December 1952, the nearly 11ft-high completed window was displayed in the reception of the Time-Life Building at the Rockefeller centre. The following year, Time gave both the window and the maquette to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 2014, both were brought together for the incredibly popular Henri Matisse Cut-Outs exhibition at Tate Modern. Nuit de Noël is an astonishingly vibrant work by an artist in his eighties still with Joie de vivre aplenty.

James White

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS