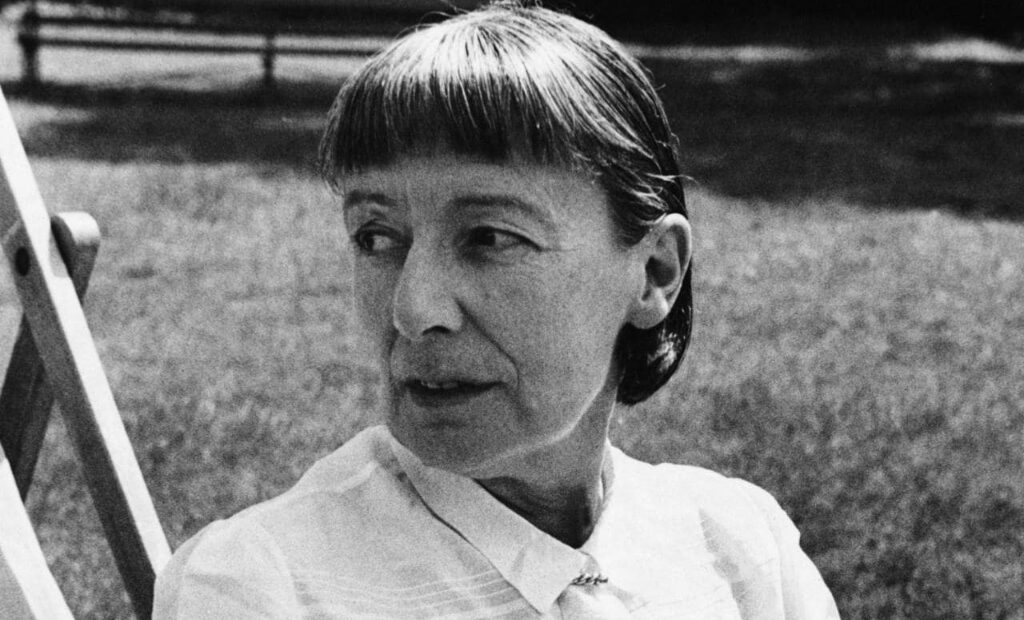

Dead Poets Live for International Women’s Day: Olivier award-winner Juliet Stevenson CBE brings Stevie Smith to life

Shakespeare’s Globe have released a film marking the 50th anniversary of the death of Stevie Smith, one of Britain’s most distinctive poets. Candlelit in the saturated intimacy of the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, Juliet Stevenson steps into Smith’s world, plunging into poetry and prose, with discourse drawn from citations and letters dancing in between. A gentle narrator contextualises, and the meeting of monologues propels a rich unfurling of the poet’s curious lifework. It’s a literary immersion.

Of Smiths’ roots, we learn of Papa: “It showed in my eyes unfortunately, And a fortnight later papa ran away to sea.” She framed her father’s abandonment as consciously willed, casting blame onto her three year-old self. “Lion Aunt” of Hull, Madge, became the anchor when her mother died, and their red-brick dwelling in Palmers Green, along with late Victorian twilight and acorn-scented parks, formed the suburban grounding echoed in much of her poetry.

Always with cigarette in hand, Smith was cynical and conversational, disinterested in the financial prosperity of fame. Perhaps the pinnacle of her success was being mistaken as Woolf for Novel on Yellow Paper, a stream of her consciousness too original to classify that brought instant recognition. She found self-expression writing through the memoirs of others, slicing meandering rhythms with pointed vocabulary, a timeless disequilibrium. Illustrations, often disturbing, populated the margins of her pages: soft scenes of mother cradling a child drawn in sharp black lines, a reflection of an anti-sentimental childhood. Childlike simplicity in her work disarms readers prior to sudden deep truths – the business of Smith’s life: loneliness, God and death. Furthermore, patriarchy persisted. The post-war movement favoured the empirical, rendering Smith and her drawings regressive – what else would be expected from “whimsical women writers”?

“I believe, I do not” – though bound to Christianity by a fear of non-belief, religion perturbed Smith amid long-held grievances. Faith was eventually trivialised in nonsense verse Our Bog is Dood; whether God is good, or God is dead, it is deliberate garble to prevent engagement with her uncertain standpoint.

Stevenson reads “Cries out aloud, from the icy shroud… His name is death,” whilst plucking petals from a flower head. Smith’s only romance was her classicism, gothic and austere; her melancholic admiration of tragedy and tenderness for death were accepted, like her lifelong loneliness. Aged eight, she found comfort in suicidal thoughts, as they implied an autonomy, but it was Madge’s passing that closed the gap between Smith and her own death. With the gradual loss of her words came the loss of her life’s fabric. Came Death, 2 became her final poem before the operation that proved her aphasia insurmountable.

Richard Church believed Smith’s tragedy was her purpose “to explore the cavities of pain”, but Smith loved life in its stoic preparation for death, and, when faced with it, never wavered from embracing that. Stevie Smith, who always wore an existence a few sizes too small, welcomed death on the 7th March 1971, as “the only god who must come when he is called”.

Georgia Howlett

The film of Dead Poets Live is available to watch online via Shakespeare’s Globe’s website until 5th April 2021. For further information visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS