Scaramouche Jones: An interview with playwright Justin Butcher

A cathartic one-act marvel that frames a century’s worth of history with the turn of the millennium, Scaramouche Jones by Justin Butcher is a twist to the classic tragic clown trope. In parallel to its own premise, the play, which was written in the final months of 1999, cites inspiration from Butcher’s own incredible backstory and journey. With a life full of ups and downs and many adventures in between, including travels all across the world, the playwright adds little parts of himself to truly achieve resonance with the audience.

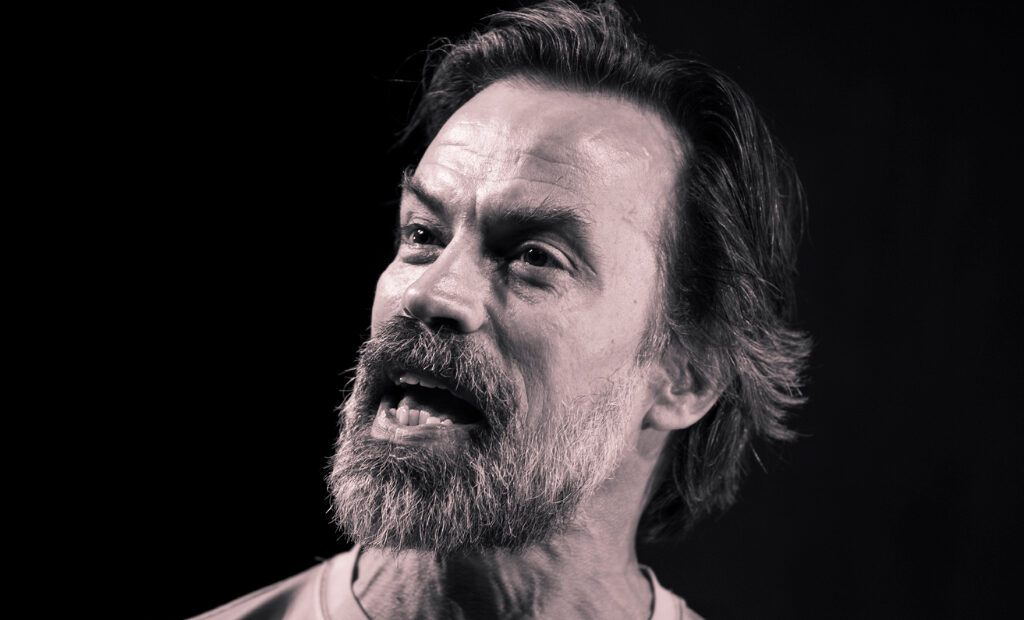

Once again, this year the clown celebrates his 100th birthday, this time under Ian Talbot’s direction and starring Shane Richie. The Upcoming caught up with Butcher as he discussed in great detail the experiences that led to the creation of the play, other inspirations for the character, and all the new stuff he’s been working on in the midst of lockdown stagnation.

What was the initial inspiration for the tale of Scaramouche Jones?

I wrote Scaramouche Jones in the final months of 1999, while I was away in Holland directing a TV series – primarily as an amusement for myself in the evenings. I was bored; I’d had a series of unsatisfying jobs, writing and directing stuff to commission for other people. This was going to be my thing – all mine, commissioned by me, written by me, performed by me. Millennium fever was in the air: what would happen when the millennium bug bit and the clocks went zero-zero?

So I set myself the task of writing a kind of comic, satirical tale of the millennium. The story of a bumbling haphazard everyman figure, born from the conjunction of the lofty “purity” of the white European overlord with the “bastardy” of the gypsy underdog; a picaresque anti-hero who stumbled through some of the greatest historical events of the past hundred years; a clown’s-eye view – a cock-eyed squint at the 20th century. Since the only goal was to write something 100% attuned to my own tastes (and if anyone else liked it, so much the better), I cheerfully chucked all my favourite ingredients into the pot.

Through pillaging the exploits of my own patchwork family – whose web of intersections meanders (like Scaramouche) across Trinidad, West Africa, Italy, Poland and even the Nuremberg Trials (the Honorable Justice Percy Rawlins was my great-uncle), with snakes, concentration camps and grave-faced actors thrown in – Scaramouche Jones also became an experiment in personal myth-making. And so, the tale is dedicated with great affection and gratitude to my family, in memory of their adventures throughout the craziest, bloodiest and yet most bountiful century in human history.

Is there a part of yourself, or at least your experiences at that point in time, incorporated into the story and the character of Scaramouche Jones?

Well, in some ways – through the tales of my family, my mother’s upbringing, the Polish and Italian uncles and aunts, the Nigerian foster-sisters and brothers etc. The world came to me before I ever started travelling the world. But look, all writers steal, I guess. Writers are magpies, collecting shiny objects, gems and jewels of pungent experience, oddities and exotic events, impressions, images, characters wherever they roam.

My father’s family had more than their fair share of tragedy throughout the 20th century. Losing cherished family members in the first and second world wars – killed in action, killed in the Blitz – and through the Poles and Italians who married into my dad’s family, came a whole series of strange, colourful and often tragic stories of their experiences surviving (and escaping) the Nazi occupation in WWII. And I’m afraid the tragedies went on after the war, in several successive generations – a real slew of extremely bad luck. But there was something about the eternally “chipper” quality of my aunts and uncles, their undimmed zest for life – gardening, literature, cooking, travel, literature, sports – which I guess finds its way into Scaramouche. At the same time, in contrast with our contemporary cultural obsession with total disclosure at all times – spilling your guts in public – there was a kind of emotional blankness, a strange gnomic quality in the face of some pretty harrowing tragic experiences, which I found intriguing and somehow inspiring.

I suppose the greatest influence of my youth must also be the worst event in my life: the tragic loss of my father and brother when I was 19. The three of us were fishing together off the north coast of Cornwall, in July 1988. Huge waves, rough weather, a tragic accident. They were both drowned. I was the survivor. I couldn’t save them. My brother was 21, had just graduated with a biology degree from London University, was planning to work and study in Africa as an ecologist – a wild, woolly, reggae-loving Bohemian man of nature. My father was 61, had just retired from the National Farmers’ Union and started up his own gardening business.

I don’t know what to say about this. It was a terrible, awful tragedy. The memory is always with me, runs right through me, woven right through me like a strand of burning copper, or a twisted rope of dark wool. Your life grows around it. New things come, wonderful things – marriage, children, work, new friends, new travels, new adventures – but there at your centre, pulsing through everything, is their dearly cherished memory, and the shock and horror of their loss.

Did you have any other specific models in mind when creating this specific character?

I remember my father taking me to see Beckett’s Waiting for Godot at the Roundhouse Theatre in Hampstead when I was around 12, with two fabulous old actors in the roles of Vladimir and Estragon: the vaudeville legend Max Wall, and the no less marvellous veteran of stage and screen, Trevor Peacock. Sitting in the front row, mesmerised, seeing these two old consummate clowns with their jowly, grotesque, rubbery faces and bendy, rubbery limbs, gnarled hands and comic gestures and expressions, fooling around for two hours… had me and the entire audience spellbound. It was quite irresistible to see how seriously they took the business of play, of being funny, of being silly. I think that was probably the first avatar of Scaramouche Jones cavorting and pratfalling across my field of vision.

Something about the concept of the play – the 100 years of life framed by the turn of a century into the millennium – is very cathartic. Why do you think audiences gravitate towards this sentimental, nostalgic sort of storytelling?

I’ve been immeasurably fortunate to have the opportunity to travel and work all over the world. Working with real people on the ground, especially in making theatre, is a whole lot more real than just being a tourist. You have to learn how to do things and say things in another language, another culture, discover and rejoice in the strangeness of those cultures, experience how people in those countries react to you, and in the end, of course, discover how on some basic level we’re all the same.

Ionesco described our experience of theatre as dépaysement – literally, losing one’s country – in which the familiar – our life, our loves, our hopes and fears, our horrors, our laughter – is made strange, clothed in unfamiliar faces, characters and stories, and experienced as if for the first time. The storyteller takes you by the hand and leads you to a strange, magical, faraway land and tells you an enchanting story about fabulous people and places you’ve never seen. And in the end, you realise it was a story about you.

And Scaramouche Jones is such a unique take on the tragic clown trope as well. What is it about this character that makes him and his experiences so endearing?

There’s something ancient and mysterious in this alchemy of satire, the healing, cleansing power of laughter, the weapon of the holy fool, buffooning, clowning in response to tragedy. The journey of Scaramouche is haphazard, accidental, seemingly picaresque, random – perhaps more like life – but it’s the defining characteristic of his white face, his greatest advantage and greatest curse, which propels all his adventures forward, and brings him at last to England, the land of his unknown English father, to whom he owes his white face. If he were still alive today, of course, he’d have got caught up in some of the most cataclysmic events of the 21st century, and he would be weirdly immune to the coronavirus, I think.

And with such a charming character, it works very well as a one-man play too. What are the advantages and limitations of writing a one-man-play?

I wanted to create a solo show for myself – something that I could perform whenever, wherever, regardless of whether anyone else was offering me other opportunities to write or perform. I’ve worshipped Dario Fo for 30 plus years, ever since I first saw a student production of Accidental Death of an Anarchist when I was an undergraduate at Oxford. Of course, Fo was the master of solo performance: writer, director, performer, producer, total theatre-maker. I suppose the English-language equivalent would be someone like Berkoff. My relationship with the theatre changes all the time depending on the project. I suppose I’m what people (slightly pretentiously) call a “theatre-maker” – I do it all. But I’m equally happy doing just one of the roles – just acting, just writing, just directing. It depends on the project.

For this adaptation, what unique sort of direction do you think Ian Talbot will take with the story?

Oh golly, I really wouldn’t presume to guess. I’ve seen a number of extremely funny open-air Shakespeare comedies that Ian directed over his many years at Regent’s Park, so I should imagine this production will be very physical, and that he and Shane will pay great attention to comic detail – the “business” of comedy.

And is there anything you think Shane Ritchie will specifically bring to Scaramouche Jones that might be different from other previous iterations of the character?

Shane is the perfect mix of comedian, old-school vaudevillian and actor, coming out of that same world that Scaramouche inhabited – comedy, music hall, panto, light entertainment – and has more than proved his mettle with some acclaimed performances in heavyweight stage roles in recent years (McMurphy in Cuckoo’s Nest and Archie Rice in The Entertainer). He’s also a great singer and dancer, and extremely fit, and by golly, you need plenty of stamina to play Scaramouche. I should imagine he’ll move beautifully on stage in this role, bringing the many scenarios to life in a highly physical mimetic, or perhaps balletic style.

The pandemic and lockdown have certainly given people ample time to take on new projects, even hobbies. Did you manage to get any new writing done over the course of last year?

Always. Currently, a verse adaptation for choir, soloists and band of Anthony Ray Hinton’s amazing book, The Sun Does Shine, telling the true story of his 30-year incarceration on Alabama’s Death Row for a crime he didn’t commit. Also a novel, or memoir, of a dear friend who was a child soldier in the Nigeria-Biafra War of 1967 to 70. A new show based on Boccaccio’s Decameron. Several radio plays. Trying to find venues to perform in… open-air theatre in Italy seems to be the only option at the moment.

What’s your favourite line from Scaramouche Jones and what message do you hope it conveys to the audience?

Blimey, what a question. They’re all my favourite, and I’m not going to tell you what message they convey – if the lines are good, you’ll get something out of them. If I have to tell you what they mean, they need to be rewritten! If you press me, it’s probably the moment when the Trinidadian beggar under Waterloo Bridge says to Scaramouche, realising it’s taken him 49 years to get to London from Trinidad (via one or two adventures): “Man! Me t’ink you mus’ have come de lo-o-o-ong way round…!”

Mae Trumata

Scaramouch Jones or The Seven White Masks is on at Wilton’s Music Hall from 15th June until 26th June 2021. For further information or to book visit the theatre’s website here.

Scaramouche Jones was available to stream via StreamTheatre from 26th March until 11th of April 2021. For further information or to book visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS