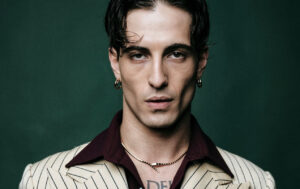

Spotlight: Raphael Dapaah on restoring Ghanaian control of cocoa supply with dairy-free artisan chocolate

With the aim of promoting a food industry that is sustainable and diverse, The Upcoming has launched a new Spotlight series, a monthly feature to give space to people, often unsung, who are changing things for hospitality.

While chocolate might be a “guilty pleasure” for many, often the deeper problems lurking behind the calories and sugar content are not given a second thought. One need only browse the supermarket shelves to see the lasting influence of colonialism: though the industry is largely fuelled by African agriculture, the labels belong to big western corporations. Dapaah Chocolates seek to address this imbalance by becoming a globally recognised brand that celebrates its Ghanaian heritage. The company uses cocoa sourced from their very own family farm to facilitate sustainably sourced bean-to-bar production. Their vegan-friendly chocolate is also eco-conscious and plans to create a solar-powered chocolate factory show a remarkable commitment to green practices. We spoke to co-founder Raphael Dapaah about the importance of origins, his reasons for creating plant-based bars and the value of collaborating with other black-owned businesses.

Let’s start from the beginning, how did you launch this new venture?

I don’t come from a culinary background or even a food or beverage background, my background was actually working for the UK government as a civil servant, as a political advisor for the last six years. The reason I actually ventured into the food and beverage industry was by chance. In 2016 I went back home, back home being Ghana, where my family originates from. I was there for the Christmas holidays just relaxing and I took a detour to visit my grandmother who lives in the western region which is sort of like the countryside – the more rural areas – and she has a ten-acre cocoa plantation. I just went with my uncle, I thought, you know what, let’s go and check in on the cocoa farm. I haven’t been there since I was quite young. It just so happened that a week prior to visiting my grandmother’s cocoa farm I’d actually read a Financial Times publication and it was talking about the cocoa industry, in a nutshell it described how the global cocoa supply chain is predominantly dominated by Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. They are the two biggest producers of cocoa globally, controlling 70% of the supply, but they only receive up to 2% of the global wealth of the chocolate industry which turns over £120 billion per annum. I remember reading that and I just remember feeling so angered by it. I was shocked. I had no idea that was the statistic. When I did have the choice to go and visit my grandmother’s farm, I thought: what can I do here to actually continue the legacy that’s already been built before? Our family had been growing cocoa since the 1920s and I’ve always had this idea that, when it comes to family business, the generations that happened to inherit should do something to add value to take the legacy or the business a bit further. In our instance, the family hadn’t done that. We had continued to grow cocoa and sell it to the highest bidder. These highest bidders will then go to turn the cocoa into chocolate in the west. I took the decision that rather than being part of the generation that’s just going to continue this cycle, it’s time that we bucked that trend. So I came back to London and essentially I did the groundwork as far as research and how to make chocolates from the bean to the bar. I spent hours upon hours on YouTube, consulting with people who were already in the chocolate industry, specifically the artisanal chocolate industry. Really just trial and error, the first thing I did was find out which equipment I needed to actually process our cocoa into the chocolate and then I just hit the ground running. After a few months, after the first successful batch was produced, I decided to bring in my siblings and make a business out of it. I guess the rest is history as far as where we are now. It’s been, from conception – conceiving the idea – to execution and launching, a two-year process.

Do you think the exploitation of cocoa production is still due to the colonial ties of western countries?

Absolutely, it’s a legacy of colonialism, it’s now what you describe as neocolonialism. It’s this relationship whereby less economically developed countries still rely heavily on exporting their raw materials to the west or even increasingly to the east, with the rise of China, rather than industrialising and adding value to those raw materials on their own grounds, to build in the factories, build in the processing labs, that are needed to create a finished product. There’s been this age-old distorted relationship of “you produce the raw materials and we’re going to add the value and then we’re going to sell the finished product back to you”. The cycle of poverty is in the hands of the producer. Again, as I mentioned, my background was in politics, so part of the reason I even got into the business wasn’t just because of the wanting to further the family’s heritage and business, but more so because of the political ramifications of doing so. I understood that we needed to fight that trend if we were ever going to ever be self-determined and not relying on just selling raw materials and being extractive economies.

Is there a new community of Ghanaian entrepreneurs in London?

I think, regarding the community, London has always been entrepreneurial by default. The fact that when you leave your country in search of greener pastures, you tend to be aspirational. Most Ghanaians came over to the UK, London specifically, in order to either further their education – pursue university further education degrees – or in pursuit of better paying jobs, so they came as economic migrants. By default, there’s a really aspirational quality to the reasons why they came over. When a lot of Ghanaian immigrants came to the country, they weren’t able to find jobs that fitted their qualifications and education. Because of that, a lot of them started their own businesses. There is this really large community of entrepreneurial Ghanaians who set up shop. Whether they started local supermarkets in the areas where they settled in or they started import/export businesses, exporting things from the UK back to Ghana and building shops back there. I think there’s also this undercurrent of entrepreneurialism and it’s something I’ve definitely benefited from.

Do you collaborate with each other?

Absolutely. I mean, one thing you may note is, one of our limited-edition artisanal chocolate bars, we tend to collaborate with other small business owners across the food and beverage industry. For example, we have a chin chin chocolate bar, chin chin being one of the most popular Ghanaian/Nigerian snacks. It’s kind of like a biscuit. There’s a local bakery in Tottenham called Uncle John’s Bakery and they are Ghanaian-owned, they’ve been around for the last 30 odd years. We use they’re chin chin in our chocolate. So for us, this is a beautiful collaboration, there’s also sort of the perfect harmony of our African heritage in that we’re using a snack that we all enjoy back now. But it’s also a bit of innovation because in typical chocolates you would never find an African product like chin chin being infused in chocolate. We’re really trying to push the envelope as far as paying homage to where we come from, our culture, our heritage, but also trying to do new things and be as creative as possible. And I guess, educate new consumers, our customers, about our heritage and get them involved as well. We’ve got so many customers who have never engaged with food products like chin chin or plantain chips before. And they love it. It’s an introduction to our culture, they’re learning, they’re enjoying it. I guess, in a way, it’s bridging the gap between different cultures.

It’s a great thing we see more and more black-owned businesses every year, what do you think is still missing to allow more and more people of colour to start their own business?

Yeah, that’s a good question. One of the biggest challenges to starting one’s business has always been access to capital, access to finance. People of colour, people in the black and ethnic minority community in the UK have disproportionately not been given the same access to credit from the bank. It’s been a lot harder to do so. That’s one barrier. I think there’s also been an issue around the marketing of goods and services provided by entrepreneurs from the black community or, in that, once people do set up shop, they’re not readily patronised. It tends to be more of a local consumption, as opposed to, where you want to grow and scale a business and be successful, the wider further you can cast your net, the likelihood is, the more successful you’re going to be. I guess it’s about driving awareness and getting the structural support, both from consumers, but also from the powers that be. Whether that be local authorities or whether that be the central government, providing support by way of grants, loans, interest-free loans, as well as just really promoting these businesses wherever we can. For example, if your business is setting up shop in Peckham, one of the easiest incentives you can give to allow people to start a business is, for example, subsidising or completely reducing business rates. I was born and raised in Peckham. And overtime, I’ve seen how Peckham has increasingly become expensive, as far as business rates and just being able to set up shop there. Some of the local businesses have been there for the last 30, 40 years, who have immigrated from countries like Ghana and Nigeria, they’re now struggling to make ends meet because the overheads are continually growing. And it’s not as though their business is growing as well in terms of the patronage. So that’s one of the barriers and issues that black-owned businesses tend to face nowadays, but I think this has also been mitigated in part by the rise of social media. I would encourage and I’ll definitely say that, for people who want to, people of black heritage, who want to start a business, they should definitely try to go the e commerce route or capitalise on that route as much as possible because it sort of overcomes some of the structural challenges around having a physical presence, having a physical premises, where rent is extremely expensive or business rates are expensive. If you can do things online and then later on, once you’re able to scale up, get a foothold, then go the route of getting a physical premise.

That’s great advice. Now onto the chocolate: how do you make a finished bar? From the cocoa beans to the product on the shelf.

It’s a cumbersome and tedious process. Essentially, cocoa beana are harvested and we pick from the pods, we split the pods and there’s sort of a pulpy fruit. Then it’s left to dry under plantain leaves. After two weeks it solidifies and turns brown. After which we bag it up and ship it to the UK. When it gets to our commercial kitchen we essentially go through the process of crunching the beans or pressing it so that it’s de-husked. The cocoa nib inside the shell is what we really need. That basically constitutes cocoa mass and cocoa liquor: we take the nib and we refine it in our melangers – melangers are stone grinders, which are the artisanal route. It’s one of the oldest traditional ways of making chocolate. We grind it – the better term is conch it – in our melangers for up to 72 hours. And essentially the cocoa liquor reduces in particle size, so it becomes as smooth and consistent as possible. Once it has gone through the process of being refined for 72 hours, the next step is tempering, which is essentially getting the cocoa liquor to a perfect molecular structure that allows it to solidify at room temperature. And then once we’ve done that we essentially package it in our recyclable craft packaging and we promote it to our discerning customers and get the word out.

How many types of chocolate do you have right now?

We have a classic range: our dark chocolate, which is a 65% dark chocolate, single-origin Ghanaian beans, single origin meaning that it comes from one farm. This is our family-owned farm, we don’t blend our cocoa with any other cocoa, it’s all consistent so we know where it comes from, the provenance is clear. We also have our “mylk” chocolate – that’s mylk spelt with a y to connote the fact it’s vegan, dairy-free. And just for some insight we use coconut milk as a substitute for dairy milk, hence why our chocolates are suitable for both vegans and lactose intolerant. That is 50% mylk chocolate.

Was it important for you to make it dairy-free?

That stroke of genius actually came from my younger brother. Originally, my plan was just to go down the traditional route of making classic dairy chocolate, but he follows a plant-based diet, so at the time he was like, it would be a great idea if you could make dairy-free vegan chocolate. I was completely unfamiliar with such a market, so then we did further research and found that it was actually a niche but growing, it had real potential. And I like the fact that, because we try to source all of our key ingredients from the African continent or the diaspora, whether that’s our cocoa, our sugar, our vanilla, by using coconut milk we could source the produce from back home. We use coconuts in abundance in Ghana so for me it was win-win. It’s dairy-free, it’s vegan, but at the same time it’s a raw material that we grow abundantly back home, as opposed to dairy, which isn’t an abundant thing. We don’t really specialise in livestock in Ghana.

Yeah and in any case dairy milk is not something you’d import from Ghana, you’d buy it locally.

Yes! So that’ our mylk. Then we have white chocolate, which is 35% white chocolate made using coconut milk. This is our classic range, but more recently we’ve introduced some limited-edition bars which basically explore collaborations with other businesses. At the moment our very bestseller is a champagne and strawberry limited edition, mylk and white chocolate. We source our strawberries from South Africa and the champagne we use is Armand de Brignac, which is more popularly known as Ace of Spades, which is co-owned by Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy and Jay-Z. So that’s one of our most popular chocolates and one which sold out in minutes when we first launched it. And another we’ve got currently is our cognac and smoked almonds. The smoked almonds are sourced by a brand called Chika’s. Chika Russell is a British-Nigerian entrepreneur who specialises in African snacks – so chin chin, plantain chips, roasted peanuts and nuts, and she received an offer on Dragons’ Den about two years ago but decided to go her own way and has since achieved great success. She’s stocked in the likes of Sainsbury’s and Asda across the UK. So again, we wanted to collaborate with another black-owned business and one that’s doing extremely well but we also wanted to collaborate with a woman entrepreneur. That was something that’s important to us and we were happy to incorporate her snacks with our chocolates.

Are you doing anything special for Easter?

Nothing special for Easter, we are exploring making Easter eggs next year. This year it’s just going to be our limited-edition chocolates on offer, but we’re looking at who we collaborate with in future to extend our product offer to Easter eggs.

Where can people buy the chocolate?

At the moment in the UK we’re only stocked on our online boutique, dapaahchocolates.co.uk. But currently we are also stocked in Los Angeles. I’d say about 20% of our orders have come from Los Angeles. I think it’s the fact that California has always had a big plant-based dairy-free culture and our limited-edition chocolate offerings are very unique. Americans have always been used to Hershey’s chocolate and the like, and from the feedback I’ve received, when they taste our chocolate it’s nothing they’ve never tasted before. It’s like what they tasted before wasn’t even chocolate, so they’ve really taken to us. We’re now stocked in an independent confectionary boutique – they specialise in artisanal chocolates as well as gourmet sweets. It’s called Tuesdays LA and they are based on Long Beach in California and they also have an outlet in West Hollywood. So that’s our first entry to the US market and we’re exploring other collaborations with US-based independent retailers.

Filippo L’Astorina, the editor

and Rosamund Kelby

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS