Jon Batiste: “Black culture has been enjoyed but black people have been marginalised in many different ways”

Jon Batiste’s first foray into music came out of sheer curiosity, when he transcribed the music from video games like Sonic the Hedgehog and Street Fighter. A few decades later, he’s become the second black musician to ever win the Oscar for a movie score (he also won a BAFTA and Golden Globe), for the beautiful and original animation Soul, the first Pixar film to have a black lead.

Having been born into a music family, New Orleans-born Batiste’s prolific career has seen him go from forming a band with his cousins as a teen and attending Julliard, to playing with legends – from Prince to Stevie Wonder – and producing solo work alongside being music director for Stephen Colbert’s Late Show (as well as playing in his band, Stay Human, on the programme).

Just released is his fifth solo album, We Are, in which the singer digs deep into his own past as well as his ancestral history. The record nostalgically recalls moments of his coming-of-age and the musical influences that underpin black and American culture, without sitting rigidly within one genre. While the bulk of its creation pre-dated the pandemic and killing of George Floyd, it reflects such events in its content, and features the likes of Mavis Staples and Zadie Smith.

We had the honour of chatting to Batiste, over Zoom from his New York apartment, about how his new album taps into the lineage of black music that is central to the American identity, his interest in the intersection between the divine and the artistic, and how, when it comes to tackling racism, it’s better to ask “what now?” than “why?”.

Jon, thank you for speaking to us. Can you tell us a bit about this fifth album, We Are? Do you see this as a culmination of your work, or is it a break with what you’ve done before?

Oh yeah, it’s a genre-less masterpiece of all the Jon Batiste things that I’ve done and more – and feels like my first album. It’s very exciting because there’s so much that’s in the album about what’s been happening in this time. You know, there’ve been a lot of protests for black lives; black culture has been enjoyed but black people have been marginalised in many different ways. This album taps into the lineage of black music and music that is central to the American identity – funk, soul, jazz, blues, gospel, marching band music, hip-hop music, New Orleans music – and it creates a cohesive narrative and a cohesive sonic world, using all of these different things, which I haven’t heard done before – and in a contemporary way for 2021. So I’m very proud of being able to create this work. It’s very, very, very powerful to me.

How does it feel to be putting an album out right now, thinking about the fact that we’ve been in lockdown for well over a year without access to live music and all the rest?

It’s a big, big spiritual calling in my life. I feel I was made to make art in this time, and that’s why it’s very special – not only to have crafted these sounds together, but the time really is the right time for the type of thing that I’m bringing to the world. So it’s a very, very special thing.

Obviously we also need to talk about your involvement in the beautiful and completely original animation Soul. What was it like being involved with that, and getting recognition at the highest level for the film and for your score?

Well I felt like I was born to do that one too. I’ve been in the right place at the right time. Because you know I’m always interested in the intersection between the divine and the artistic, divinity and artistry. Where do they intersect? And how it really is a great thing to ponder in your work. You know, divinity begets artistry. And artistry is really represented best when you look at the divine nature of existence. Look at nature, look at trees, look at the sky, look at birth, life and death, cycle of life – all these things the film is really talking about, in fact they’re central to the film. Jazz, music and where the soul comes from – it’s like I was born to do it. And it’s this black jazz musician in New York City, and I moved to New York when I was 17. And I’m 33 when I’m making this score and when I’m putting this album out and all these things are happening in my life. But I can still relate to Joe, who has this dream that he hasn’t fulfilled. And it just is great to work with Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross – you know these are two great rock’n’roll musicians and film score musicians. And we were three voices that became one. It all was a great experience.

What did it mean to you to not only have been involved with a one of the first mainstream animations to have a black character front and centre, but also to be the second black composer ever to have won the Oscar for best soundtrack?

Yes it was amazing because I talked to Herbie Hancock, who was the first ever of all time. I went to his house and it was a funny realisation – being the second of all time and getting together with him. I’ve been knowing Herbie for some time, but we really got to hang after the Oscars, which was a special hang because I went over there and we played the piano. We’re hanging out and then a couple of hours later he’s like, “Man, I got to show you my Oscar.” And then he showed me the Oscar. And he won the year that I was born! 1986. So again, I think there’s some divinity in that.

And then we went to chant, because Herbie is a Buddhist and he’s very much into chanting, and we started to talk about the way that the chant that he was teaching me is his way of connecting to the universe, and then, if you connect it to that frequency when you live your life, you’ll see everything through the bigger perspective of how the universe and everything is connected, and you won’t see suffering the same way. You won’t see anything the same way – it’ll all be from a more enlightened place. And it was just a very interesting and beautiful gathering, you know, when we got a chance to hang out. But to connect that, to look at the year he won for Around Midnight, which was this jazz film, in 1986, and then now 2021, talking about it after I’ve won for the first black Pixar lead film, and I’m the second black composer to win – it was all really special and unique to have the conversation. That’s not a conversation that you can have with anyone – I mean he’s the only person in the world I literally can have it with! And the fact that he’s still with us – you know he’s 81 and as he’s seen so much since then – and I was born when he won. It’s amazing.

Do you also think are kind of two sides to it – because on the one hand it’s amazing that it’s been achieved, but on other hand you might think, “Hang on why is it so rare? Why is now only the second time a black composer is winning that award? Why have we not seen more animated films with black characters front and centre? Do you feel that it’s a great sign of progress but it also highlights the fact that perhaps progress has been too slow thus far?

Well I feel that it’s hard to imagine… it’s hard to conceptualise all the reasons why that is the statistic. It’s like when you think about why there’s so many – in our country in particular – why there’s so many blacks on death row or people of colour in jail. There are so many negative statistics that if you view it from that filter, I feel like there’s a mountain of reasons why, and it almost feels insurmountable. Whereas if you view it from the way that I see it – which is why I led a protest of 10,000 people in Manhattan after George Floyd was murdered, or why I did a voter registration rally on the steps of the Brooklyn public library before this past presidential election – it’s more… I see it, like, “what can be done now?” versus “why?” Because the “what” is a more productive question versus “why hasn’t there been progress?”. You know, I think that if you look at Dr King or, you know, Mavis Staple – all these activists, musicians, people I look up to – they were asking the question “what can we do?”. It wasn’t about necessarily “why?” as much as it was about “what now?”. You know your history so you don’t repeat it.

How does that make you feel looking back on what you’ve achieved at such a young age? Can you speak a bit about how you came to carve out this career? Did you think when you were transcribing music from video games that you’d be getting an Oscar 30 years later?

No, I just decided to make music because it was fun. It was something that my family did. My cousins, Jamal and Travis, my older cousins, we formed a band together and it was fun. And then I started to really get inspired to do it. Then I realised I had a special talent to make music that people were interested in. And I didn’t know it was special until they told me. And by then I was a teenager. So by that point that’s when you start thinking about what you want to do for a profession. You know: do you want to go to college or do want to go into the service and the military, the army, or you want to go on the road and tour or you want to go be a doctor and everybody’s talking about all of that stuff. And I’m like, “Well, maybe I’ll go to New York and keep pursuing music.” And then I moved to New York at 17. And from 17 until now, I’ve basically just been pursuing creative projects, mentorship opportunities to learn – I’m always soaking up information – and just building a career based upon things I’m passionate about doing. And that always leads to other opportunities, and leads to meeting people, and leads to meeting more people and more opportunities and more creative projects and more inspiration, and just kind of compounds until – what do you know? That’s why the rest is history!

You’ve already performed with and made music with so many big names in the industry. Who would you say are your ultimate idols and are there any people that you haven’t yet worked with that you’ve still got on your bucket list?

I’ve worked with a lot of the older musicians who, you know, some of them are passing away. And I’m fortunate to have had the opportunity to play with them, many of which are no longer with us. But now I’m more interested… not that I’m not interested in playing with the legends, it’s just when I have, they’ve passed their prime and don’t play anymore. I missed playing with Sonny Rollins, I wish I could have got a chance to play with him; he’s not playing anymore. And Jimmy Heath, he passed away, I played with him. Played with Curtis Fuller, Louis Hayes, who’s still here with us. Curtis just passed. Abbey Lincoln, you know, Max Roach, Roy Hargrove – all these legendary jazz musicians. I played with Prince, passed away. Man. So I guess I want to play with my contemporaries now. Like Lady Gaga – Stefani Germanotta – I want to play with her, that would be fun. I think I really would love to collaborate with her on something. Yeah that’d be really cool, I can see it.

That definitely needs to happen! And what have you got planned for this year? And are you feeling optimistic?

So yes, we will perform! We have some performances coming up – about five that are coming up later this year. And then I have a symphony called the American Symphony. It’s the largest scale work that I’ve ever performed and composed, and it’s a 40-minute, four-movement symphony. Hundreds of musicians. The Carnegie Hall premiere is in May, a year from now – May of 2022. And I’ll be performing a lot between now and then with We Are. And at Carnegie Hall I’ll also do some of We Are, as a prelude to the symphony – so there’s going to be a lot of great, great moments in the times to come!

What have you missed most about performing live?

The people. Yeah the energy of people in the space together listening to the music and the feeling of that exchange. You cannot replace it. It’s different to anything else. And I think that, when it’s at its highest level, it’s one of the best feelings for the audience and the performer.

I loved what you said in your Oscar’s speech about there just being 12 notes – it’s so true that with something so simple you can have something so rich. And do you hope that post-pandemic we don’t lose anything from our cultural heritage?

Well I think the 12 notes of music are like all of the different shades of people. And you know in microtonal music you can go in between the notes and get back to the note that you were at at the beginning. It’s like all of the different shades of humanity. Different cultures, the different voices and the experiences and the different blends of cultures that create new cultures. And that’s what music is like. And I think that it can be such a universal global force. And I’m excited. I’m excited to see where it goes.

Amazing! Well thank you so much for sharing all that with us and let’s hope this year sees a return to some normality. Or at least we can all be listening to music together!

Yes! We will have music.

Sarah Bradbury

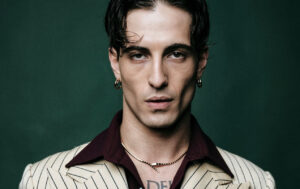

Photo: Louis Browne

We Are was released on 19th March 2021. For further information or to order the album visit here.

Watch the video for the single I Need You here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS