Spotlight: Urban Farmers and the food apartheid rebellion through the eyes of Valery Rizzo and Monica R Goya

With the aim of promoting a food industry that is sustainable and diverse, The Upcoming has launched a Spotlight series, a monthly feature to give space to people, often unsung, who are changing things for hospitality.

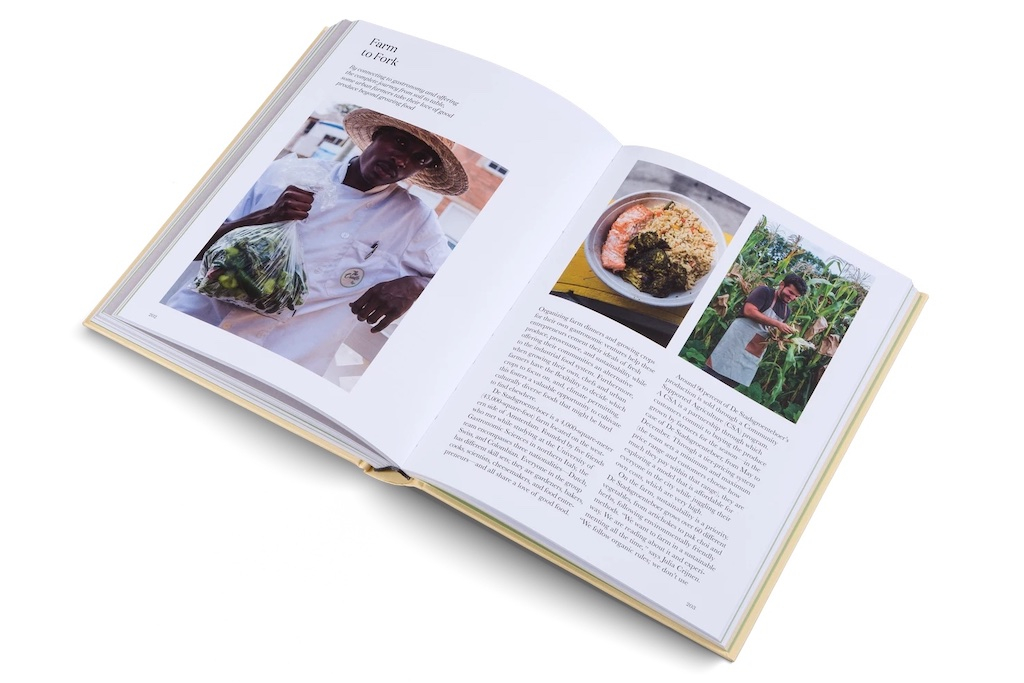

This month we turn our attention to two pioneering female photographers, Valery Rizzo and Monica R Goya, and their new book Urban Farmers. Though living worlds apart, the former a New York native and the latter a London-based European citizen, the pair formed a friendship on Instagram, and after capturing and meeting in two of the world’s most iconic cities, their joint passion for agriculture and the environment led them to collaborate on this eye-opening global project. The book explores the many multi-faceted advantages of urban farming, from the eco-friendly angles of sustainability and biodiversity to the less obvious benefits felt by local communities. We spoke to the pair about food apartheid, non-profit urban farming as a means of making fresh, healthy produce affordable to all and the importance of knowing how and where your food is grown.

This is a fantastic book, congratulations. First off, urban farming is still a new concept to most people – how would you describe it?

Valery Rizzo: Urban Farming may be a new concept to some, but it’s certainly nothing new. What is new is the explosion of interest and all its new forms along with the realisation of the numerous benefits it provides, physically and socially. Urban agriculture, urban farming or urban gardening is the activity of agricultural or livestock cultivation, processing and distribution in cities (sometimes per-urban); it comes in different physical forms and allows for a variety of benefits to the surrounding community.

Monica R Goya: Simply put, I’d say it refers to growing and producing food in an urban environment.

You are both experienced photographers in two of the world’s most iconic and interesting cities. What sparked your particular interest in urban farming as a subject?

VR: As a photographer I became interested in Urban Agriculture when I discovered Eagle Street Rooftop Farm, the first rooftop farm in Brooklyn, in 2011. Being a native New Yorker I was intrigued by the idea of a farm on a rooftop in the city. I later went on to photograph Brooklyn Grange Rooftop Farm during a visiting artist residency at The Brooklyn Navy Yard and at the same time I began to photograph Brooklynites in their backyards growing food and raising chickens for another project focused on Brooklyn. I thought this was a wonderful way to connect New Yorkers to their food source while also providing a much-needed green space to an urban environment. I also started my own backyard raised bed garden where I experiment with growing my own vegetables and pollinator perennials and I belong to a neighbourhood food-coop. More recently I had learned about a great initiative from the city of Paris through Les Parisculteurs to green the city with agriculture and I travelled to Paris to photograph some of the numerous agricultural projects developing there. I started to envision the possibility of documenting urban agriculture around the world, and I am constantly in awe of the growers, the methods they use, their lifestyle and the importance of it.

MG: In my case, on the one hand I became interested in urban farming from a sustainability perspective: I couldn’t help but ask myself, how can cities become more resilient and more sustainable in the future? On the other hand, after some time in London I missed the countryside dearly and some urban farming projects made me feel closer to it.

Photos: Valery Rizzo (left, Edgemere Farm) and ØsterGRO (right, ØsterGRO farm)

Urban farming is not just about agriculture; it can also be about alleviating systemic inequality. Tell us about the non-profit side of urban farming and why it’s important.

MG: There are dozens of examples of urban farming improving food access for the communities in which the farms are based, like for example East New York Farms!, which is included in the book. The advantages of growing healthy, affordable fresh produce in the city are numberless and have many layers, including making people consider where the food they eat comes from, or the working conditions of the people who grow the food for us. Also, it’s especially relevant in communities that lack access to fresh food, maybe because they are located in a food desert (areas where people have limited access to a variety of healthful foods), or maybe because ultra-processed options are the only affordable ones. Additionally, it’s been proven that children who are familiar with growing vegetables are more likely to eat them. Healthy food should be affordable for everyone and although urban farming isn’t a solution, it has the potential to help.

The concept of urban farming is often presented in contrast with the over- industrialised evolution of our society, but there’s actually a lot of technology involved, right?

MG: Absolutely! Some urban farms are incredibly sophisticated and use the latest technologies to be more efficient, to the point that they might look more like labs than farms! For example, when it comes to water usage, some farms have sensors that allow them to provide the exact amount of water needed. Others grow herbs under LED lights… the array of current options is incredibly diverse.

Can you explain “food apartheid” as human-created system of segregation and urban farming’s place in addressing it?

VR: Apartheid is a system of institutional racial segregation and discrimination; the term “food apartheid”, coined by activist and renowned urban farmer Karen Washington, correctly highlights how racist discriminatory policies have by design shaped areas (often labelled bureaucratically as “food deserts”) by using methods of systematic racism and oppression to deny people of colour access to nutritious and affordable food, farmland and business opportunities in the food industry, in the form of zoning codes, lending practices and other discriminatory policies rooted in white supremacy. There are many organisations already working on addressing this, with ideas from policy reform to building alternative food system models. Urban Farmers are working on more grassroot food justice movements to transform the food system which makes healthy and affordable food accessible to all, encourages more education and healing and support for BIPOC-owned farms and reparations.

MG: The term food apartheid was coined by the food justice activist Karen Washington, which she considers more appropriated than food desert because according to her, the latter doesn’t take into account the systemic racism permeating America’s food system. I believe in this case urban farming might be a stopgap measure, but the solution is much more complex than that and it requires, among other things, a dialogue involving politicians that seem to be the ones with the power to really end the disgraceful reality of food deserts/food apartheid in the US.

Photo: Valery Rizzo (Wilk Apiary)

What inspired you to write the book Urban Farmers together? Was there a particular personal moment that led to your collaboration or was it a culmination of encounters?

VR: When I was asked by Gestalten to further explore my idea for the book, I was also asked who would write the book. Mónica was one of two people who came to mind and in the end was a brilliant choice. Both of us being photographers, Mónica and I had formed a friendship over the years through Instagram, later meeting in New York City and London. Mónica is also a journalist from Spain, living in London and has written often about agriculture, especially wine production. I really liked the idea of her being on the other side of the pond, as they say, and very connected to Europe while being fluent in French as well as Spanish and English. We have also always wanted to collaborate on a project together and this opportunity was perfect.

It must have been a long, intense process. What have you learnt from each other?

VR: It was an intense process. From start to finish it was about a year in the making, which seems long, but given the topic was also very short at the same time. I was so thankful to be able to work with someone as intelligent and kind as Mónica and I learned alot about patience and communication and working with a team remotely and all during a global pandemic.

MG: I feel incredibly grateful for the opportunity to write this book. Valery is a photographer whose work I have long admired and I feel very fortunate to have worked with her and the Gestalten team on this project. Her attention to detail and her capacity to respect and consider everyone that participated in the process are two things that I really appreciate.

There is, of course, a big environmental factor at play. Given its emphasis on self-sustainability and locally sourced produce, does urban farming have a role to play in combating the climate crisis?

MG: Yes. Although many of the people I interviewed for the book mentioned that urban farming cannot feed entire cities nor should it try, the role of urban farms goes well beyond growing produce. They can also help with water management, improve air quality, reduce the urban heat island effect… also cut down the carbon footprint of the produce that is grown only a couple of miles from where it will be eaten. To an extent, all these can help mitigate climate change.

How might Urban farming help promote biodiversity?

MG: Usually, urban farms grow dozens of different crops, from beans to herbs or berries, including heirloom varieties as well as culturally significant crops for their communities, which is very beneficial for biodiversity (as opposed to mono-cropping). Also, experts talk about how cities could become a refuge for biodiversity, for example for pollinators, which sadly are suffering the consequences of excessive use of pesticides.

Photos: Valery Rizzo (left, Meredith Hill) and Thomas Vickers (right, Ron Finley)

Urban farming has been described as a kind of “buffer” for cities in times of crisis such as Covid-19. How can urban farmers be a positive force for change in their communities?

VR: Having a local farm where you can buy fresh vegetables, either through a CSA, a farmers market or just stopping by to pick up some fresh eggs, keeping it local in the community can alleviate the problem of empty shelves at the supermarket and the issue of safety and long lines that were present during the pandemic. Urban farms and in the wider context urban green spaces, like community gardens, can also provide a much-needed oasis in times of crisis and can have a positive impact on mental health and provide a place for the community to connect.

MG: In my opinion one of the most relevant things is that they can get their community involved and change the lives of so many people, especially city kids who maybe don’t have access to the countryside and aren’t familiar with the process of growing food. Another aspect of it is its capacity to raise awareness of the significance of where the food comes from, as well as providing green spaces where people of different backgrounds can meet each other.

Have you seen this first-hand? Tell us about one of your most inspiring stories from the book.

VR: In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, Brooklyn Grange altered their food donations to 20 percent of their total production. With the closure of many restaurants, who they would normally sell to, and the unprecedented need for emergency food relief, they shifted their crop plans over quite a bit to crops that make more sense to families in the community that may be struggling to put food on the table. Through fundraising and charitable partnerships they were able to cultivate and donate these slower-growing, calorie-dense crops, which are often less profitable but more meaningful to the surrounding community.

East New York Farms! is one of the many inspiring stories and essays in the book. Located in a culturally diverse and underserved community, they operate two farms – one a youth farm and the other a farm in a public housing development – and two community gardens, while providing support to numerous other community gardens in the surrounding neighbourhood. East New York alone has over 60 community gardens. They also have a weekly farmers’ market outside of the youth farm where community gardeners can also sell what they’ve grown in their gardens and at The Pink Houses Community Farm they have a weekly food distribution to local residents. Additionally, they also compost and have bins outside of the farm for local drop-off of kitchen scraps as well as free soil testing and distribution a couple times a year. I witnessed first-hand how all of this work brings the community together in a positive way.

Photos: Michelle and Chris Gerard (left, Michigan Urban Farming Initiative) and Valery Rizzo (right, Brooklyn Grange Rooftop Farm)

Do you think food should be a political tool?

VR: I think food is a human right. Everyone should have access to healthy and affordable food and the more control people have over their food system the more power they have to change it. Both through policy reform and grassroots efforts, power can be restored to the people. In a city that could mean healthier food, tackling inequities, preserving and creating biodiversity and bringing positive change to the environment and the surrounding community, all through growing food!

MG: In “The Pleasures of Eating”, Wendell Berry said that eating is an agricultural act. Adding on to that, writer Michael Pollan argues that eating is a political act and that we should consider the link between what we eat and how that food is grown. Sadly, one of the most devastating forms of inequality is hunger. It’s shameful that so many millions of people don’t have enough to eat. There is a fantastic book by Argentinean journalist Martín Caparrós called Hunger that I really recommend. All this to say that it’s a privilege to be in a position to consider how food is grown or where the food comes from. By supporting one farming system or the other, those who can choose are making a decision that has huge consequences, even if they might not be aware of it.

What kind of diversity have you encountered in the farming community? In terms of genders, cultures, backgrounds and ideas.

VR: The people featured in the book are growers, activists, advocates of food sovereignty, chefs, educators, beekeepers, horticulture and environmental science students, viticulturists, gardeners, biodiversity experts, seed keepers, community growers from necessity or for ancestral connection, agronomists, youth volunteers, agrobiotechnologists, artists and designers, software engineers, urban planners, food activists, thermal and agricultural engineers, environmentalists, postal workers, food entrepreneurs, bakers, cheesemakers, scientists and homesteaders. All are fascinating and diverse in terms of genders, cultures and ideas.

MG: In my experience, urban farming seems to be more of a youthful venture, while farmers I know who live in the countryside tend to be older. Each farmer probably has a different reason why they decided to follow that path. Some people do it as activism, for the benefit of their community, others just as a profitable business, others are working with the environment in mind…

Photo: Courtesy of Chicago Botanic Garden (Windy City Harvest)

What advice would you give to someone who wants to start urban farming but doesn’t know where to begin?

VR: I would say to start by growing something yourself in whatever space you have, be it a balcony, fire escape or backyard or join a community garden or allotment. If you really want to work in the field of urban farming, I would start by volunteering at a local farm and maybe trying different types of agriculture until you find what you like. You could also go further and study agriculture – the options nowadays are endless.

MG: To spend time at different urban farms and to contact urban farmers who have done what he/she hopes to do and ask them for advice. Urban farmers are great people!

Rosamund Kelby

and Filippo L’Astorina, the Editor

Photo: Valery Rizzo (cover image, Topager’s Opéra 4 Saisons)

Urban Farmers: The Now (and How) of Growing Food in the City is published by Gestalten and available to buy from their website as well as major retailers. For further information about the authors visit Valery Rizzo’s website and Monica R Goya’s website.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS