“The body can be a totem for all the anxieties we share but no one wants to talk about”: An interview with Julia Ducournau on the radicality of Titane

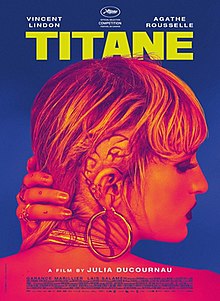

Titane (French for titanium) is Julia Ducournau’s daringly provocative body-horror follow-up to 2016 feature debut Raw. It stars first-time actor Agathe Rousselle as Alexia, who is involved in a car accident caused by her father as a child and left with a metal plate in her head. As an adult, she’s a dancer at car shows and when a creepy fan takes things too far she takes brutal revenge, but then must go on the run, setting in train an unexpected set of events.

The gruesome, off-the-wall film that explores trauma, identity, gender roles and love has divided critics but has also won Ducournau the Palme D’Or at Cannes, with her becoming only the second-ever female director to have received the plaudit.

Everything about this film is extreme – the aesthetic, the violence, the sensationalism. It is through the body that most of the story is told: we see it at its most vulgar, grotesque and pushed beyond the very limit of its conceivable possibilities as it’s torn, stabbed, injected, stretched, compressed and seen combined with metal in more ways than you can probably think of. It’s also the site of Ducournau’s fascinating discussion, inversion and total debunking of notions of gender, with the stereotypical constructs of masculinity and femininity built up and dismantled time and time again.

There’s no question it’s one of the most messed-up films to be released this year. Or maybe ever. As one older female critic exclaimed as leaving a screening: “What f**ked-up stuff does that woman have in her head?” But it’s also cinema at its most bold, fearless and envelope-pushing.

We had a chat with Ducournau about the inspiration behind the groundbreaking film, casting Rousselle as her murderous, androgynous, car-shagging lead Alexia alongside industry veteran Vincent Lindon, and how the film is ultimately about unconditional love.

Hi Julia, so lovely to have the chance to speak with you. I understand that after you completed Raw to critical acclaim in 2016 you went through a period of self-doubt and weren’t sure about the film you were going to make next. So what was that experience like for you? And how do you think that led you to this film? What was the trigger that finally made you realise this was the film you wanted to make for your second?

Well, that was not easy at all, to acknowledge that. For Raw, I was on tour for two years after Cannes. The release of the film was a year after Cannes, which meant that for a whole year, I went through the festival circuit all around the world. And then I had the promoting tour with the release. And then I had the award ceremony tour. By the end of the Cesars, which are the French Oscars, I had been with the film for more than six years and it’s quite a lot. And my first reaction was to rush into a first draft for my next film, for which I had the idea when I was in post-production for Raw but didn’t have time to develop anything more. And so I rushed into this first draft which was virtually unreadable – 190 pages and all over the place. Really, messy as hell. And after that, maybe because it was too big of a draft and also because Raw was still very present in my life, I started blocking, you know? Having this writer’s block. I could not write at all. And this lasted for a year, which is fairly a lot when you think about it. And it’s not like you stop and you go to the restaurant with your friends, you take a few holidays here and there. No, no, there was nothing like that – it was really just waking up, taking a shower, getting dressed, taking my breakfast, all that, sitting in front of my computer, and just waiting, every day for a year. So that was a very painful experience, I hope I don’t go through that anymore. But at the same time, I think, in the end, in retrospect, it was very profitable. Because I do think that the radicality in Titane, and the energy that it has, does stem from all the doubts and all the fears that I had, during this moment. Also, the anger, because I was very angry at Raw, you see, because Raw was taking way too much space in my life. And I could not let go, which made me fairly angry. All that and questioning my love for my second film, wondering if I would be able to love my second film as much as I loved my first one. It was really an in-depth process. And at the end, I was in such a state of being fed up with all that, that I just thought, “F**k off, I’m just gonna write whatever I want.” And whether it makes a film, whether people like it or not, has like nothing to do with it. And that’s when I started completely messing with the structure: I had a three-act structure for the first draft that I completely kicked out. And I started to go with my instinct and go layer by layer. And this is how you get this very ascending structure that starts in a very Baroque way and ends up in a very simple set up in order to get to the core of the emotion throughout the film gradually. I think Titane would have been very different if I hadn’t gone through that for sure.

In Titane you successfully amalgamate all the important facets of human life like mortality, birth, instincts, violence, love, pain and more. How did you develop the story and characters to explore all these crucial elements of human life in less than two hours?

It’s a good question. You know, the thing is that there is no agenda when you’re writing. You’re not like, crossing boxes, thinking, “Yeah, I got this theme, I got this theme as well.” Nothing is like an agenda; it goes pretty naturally with the characters. The only thing that is important are the characters, and for you to be with them constantly. And so in the end, it probably stems a lot from things that I think about a lot myself. But it’s not done in a way that was planned or anything. Like the fact that she takes on a fake identity of a teenager is something that for me makes sense in the journey of my character, trying to run away from the cops and having this idea that she thinks is the only exit, at least in that moment. And then that obviously triggers this whole question about the notion of gender and what it means and but more than anything, you end up on this very simple setup of two people finally being able to express unconditional love for someone else. Like in the bedroom at the end, you discover that gender is actually something to get rid of in terms of representation, in terms of it being a social construct that prevents my characters from loving each other truly, and all this really is always all about the characters and thinking about their journey. Also, for example, in the choice of their jobs: she’s an exotic dancer in a car show, and he’s a fireman. Well, this was clearly intentional, because, in order to debunk the stereotypes, you’ve got to show the stereotypes first. And then, it’s what you do with them in order to try to make them move more and more blurry. And to actually try to debunk them, divert them, and in the end, kill them. So yeah, I don’t know if that answers your question!

It does! Ultimately our bodies are nothing but cells and flesh and matter. So although some people are shocked by both Raw and Titane you could say they just present the human body and the extremes that it can go through: instincts, needs and urges. Do think that people are often uncomfortable with what’s under their skin?

Yeah, I think so. You know, there is this thing that’s really funny. I’ve been working on bodies for quite a long time, although I’m very young in my career – since my first short it has been about that. And even the shorts I did in film school were about that. And it was already about opening up the body, and I’ve noticed that there is something – it has to do with what’s unsaid, what’s taboo. Like, your skin is protecting you from getting too deep or showing too much of yourself or also facing your mortality, which is pretty taboo in our Western civilisation actually. And it’s incredible how the body can really like be a totem for all these fears, all these anxieties that we share, but no one wants to talk about. And for me, that’s why I’m so passionate about expressing things through the body. It’s not like I’m crazy about bodies like I’m not fetishising, it’s not a fetish. But it’s really like, what can be said through the body is really talking about us really, it’s talking about this dialogue, this conversation we never have – whether it’s gender, whether it’s mortality, whether it’s vulnerability, whether it’s inner pain and all that – it’s things we never talk about and personally, I hate leaving things unsaid. And God knows there are many unsaid things in the world that will allow me to make more films afterwards. But it’s insane, everything you can really convey with the body, with the experience of the body, the experience of pain. Like, for example, when we shoot, I never put makeup on my actors, I don’t do beauty makeup. I don’t do that. It’s not that my films are very realistic because they’re not. And I’m not a good example for that right now because I have eyeliner on! But it is something that is quite moving, showing the skin as it is, showing it with the pores and the dark veins and the hair and the sweat and all that. I want to show my characters the same way we see each other at the end of the day, when we take off the makeup and we haven’t shaved our legs. And we find ourselves too fat or too thin. This is something that we never talk about yet it happens to everybody – no one is satisfied with their own bodies, no one. And we pretend like we wear the right clothes, sometimes women wear Spanx and we try to look like something we’re so not. So I think it’s interesting to find this in characters because it makes us relate to them, even though we can’t necessarily stand by them morally speaking or anything. But through this very endearing vulnerability of the body, we can relate to them. And that’s where I find beauty. That’s what I like.

How did you decide on your cast and how did you work with them? Because on the one hand, you’ve got a screen veteran in Vincent Lindon and then you’ve got a completely fresh face in Rousselle. But for both of them, they’re really put through the wringer in terms of the physicality of their performances, the nudity and some of the more extreme scenes such as when Alexia’s in the car and the scenes towards the end of the film. So you know, what was that whole process like for you? And how did you know these were the right people for your film?

The idea to work with a newcomer and a legend was clear from the get-go. For me, it was interesting, because I expected both would have very different energy. So for Vincent to be very channelled and very grounded on the set and the newcomer to be a bit all over the place, but have this energy of someone who really wants to push things through and to go for it. And at the same time, I knew one thing is that none of them had ever been in one of my movies. And by this, I mean that Vincent had never done a genre movie, and he had never done anything related, really, to our bodies and stuff like that, and she hadn’t done anything at all. And the thing is that putting them together on set with both their energies, it was kind of like it’s was both their first time as well. So I knew they would share common ground also through that. Also because none of them really had the keys of my universe. And I give some keys, but I don’t give all the keys, on set or even in pre-production. I’m very, very transparent as far as anything that has to do with the body, everything that has to do with nudity – I always tell them what I’m going to do, what I’m going to shoot, always keep my word, obviously, for that. And always preparing them mentally before, to tell them, “this is this is going to be a hard scene, we’re going to be doing this and that” so that they feel safe. But at the same time, they don’t know my universe, they don’t have all the keys of what the movie is gonna look like because I don’t show them any images at all – to anyone, actually. So it’s kind of a leap of faith, they have to step into the dark. And that’s normal. In return, I give them that safety that if they’re uncomfortable with something, then we don’t do it. And obviously smaller crews for nudity So that’s how I work. And that’s how I knew that I would not consider them differently on set. That’s the thing. Also, I actually wrote for Vincent. So for me, the casting for his part was certain. We’ve been friends for a long time, and I know the way he works. He’s a very corporeal actor as well. So that was a perfect fit for my film. And also he’s very, very skilled with emotions, like Vincent is fearless with emotion and his character is the only emotional bearer we have in the film. And so it was important for me that it’s him because he’s like, fearless, he goes 100%. Because he’s so skilled, it’s always channelled in a good way, you know? And with her it was more knowing I was going to work with non-professionals, knowing that I needed an androgynous look, knowing that men and women would cast for the same part, knowing that I needed someone who had potential and that I really wanted to film. The casting lasted six months, I guess did five or six rounds. I really wanted to film her because she has amazing angles on her face and she changes, actually morphs according to where your angles are and what the light is. Completely morphs, it’s fascinating. And after that with her, it was a year of work on her acting and obviously on the physicality as well. Just as Vincent also had to do heavy lifting for a year and a half.

It’s incredibly thought-provoking that you play a lot with the notion of gender. For example, Alexia’s androgynous appearance is just an introduction, but it’s not the pivotal point of the story. There’s also the stereotypical importance of the cars in the film and how it’s like an indication of masculinity which Alexia kind of destroys and it’s intoxicating to watch. What can you tell us about the use of the image of the car?

For me, from the get-go, it was really clear that that’s cars were seen as an extension of masculinity. That’s the only reason I wanted to show cars. I mean, I don’t even have a driver’s licence, so I don’t care about cars in life. I’m very much interested in the inside of the cars, what I show at the beginning, under the hood, and under the car itself. I liked the idea of trying to film something like the dead metal, the dead pipes and to film them like their bowels, like the inside of someone. So that’s what I tried to do in the first images of the film; that really interests me, to try to make something alive. And also it’s a big echo to the ending of the film where the metal on the baby is alive because it’s moving with him and stuff. It’s no longer this dead part that she has in her head that makes her completely outside of humanity and dead inside, pretty much. Then for example, in the car show “oner” – I decided to make it a oner because through it I actively wanted to reverse our take on the action, on the girls and on the dancing. So at the beginning, I tried to mimic a male gaze that was looking at the car and looking at the girls in the same way, like objectifying the girls and somehow anthropomorphizing the cars, if you wish, so exactly in the same way. Then when we get to her, this is where I’m trying to make our take on it change. Because, for me, she’s not dancing next to the car as an accessory anymore. She’s dancing with the car. So it’s already establishing a relationship with that particular car. And the fact that she looks through the camera lens makes us passive when she was supposed to be passive, but she reclaims the narration as being active because she’s looking at you, and you’re not looking at her anymore. So the whole thing I did with that car was important because of what cars represent, and how men treat the car as an extension of their pride and all that and to have her desire and her strength kind of overcome that. And this is obviously enhanced in the moment, the scene where she has sex with the car, where the point was really to make-believe in seduction between the two of them like really make something quite sensual, you know? Not in a fetishistic way, but really like believe in that relationship, that you could see as a work relationship, by the way. Also, the idea was that, again, her desire here, coming to a climax, was really overtaking the idea that the car would be stronger and more like prominent than her in the act.

Thanks so much for sharing all that with us! It’s been an absolute pleasure to speak with you.

Thank you!

Sarah Bradbury

Titane is released in select cinemas on 26th December 2021. Read our review here.

Watch our red carpet interviews with Julia Ducournau, Agathe Rouselle and Vincent Lindon here.

Watch the trailer for Titane here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS