Francis Bacon: Man and Beast at the Royal Academy of Arts

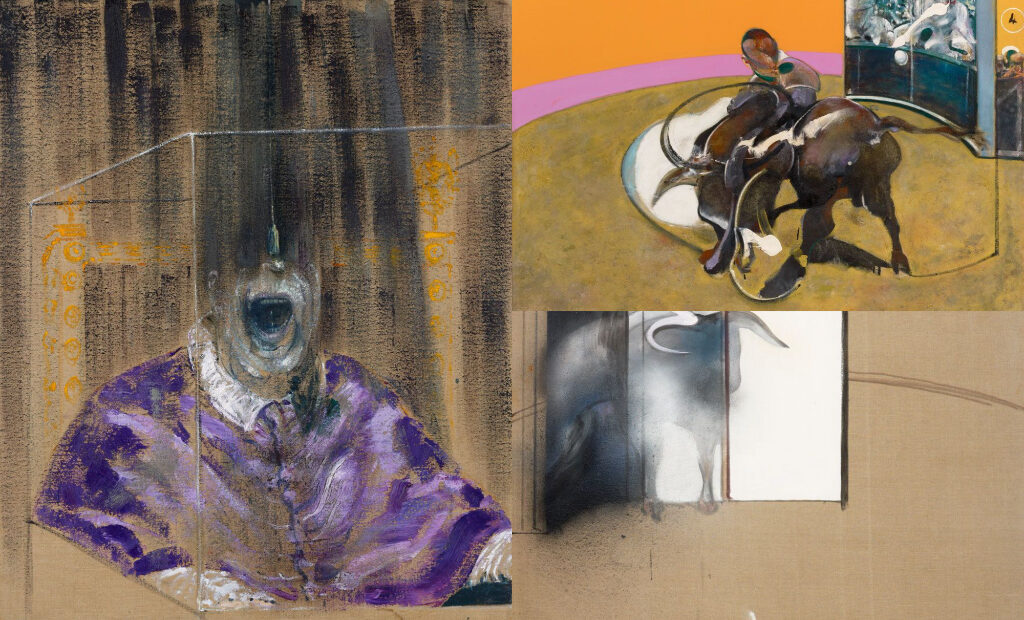

30 years after his death, the visceral, raw imagery of Francis Bacon has lost none of its power to unsettle and shock. The Royal Academy’s new exhibition, Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, co-curated by Dr Michael Peppiatt (a close friend of the artist) throws into sharp relief Bacon’s fascination with animals and how it informed the development of his human figuration. Featuring 45 paintings that span nearly six decades of his career, this Covid-delayed show carries serious existential wallop.

Bacon saw humans as animals like any other. That’s a reality he explores repeatedly in this far-reaching exhibition, constantly conflating the boundaries between homo sapiens and the animal kingdom. The artist’s father was stud farm owner who banished the then 16-year-old due to his homosexuality, and horses are notably absent in the exhibition. Testament is made, however, to the impact of the two wildlife trips he made to his family in South Africa in the 1950s. Over the years he would study animal photography for inspiration. The screaming, tilted-back heads appearing here at the RA (embodied by the biomorphic creature in the right canvas of the Second Version of Triptych 1944, painted in 1988) derive from a photograph of a chimpanzee he used as source material. The show at times usefully juxtaposes the magazine cuttings and photographs of animals with the pictures they inspired.

Head I (1948), the first work on display, accords a room of its own. It depicts a fanged mouth – taken from a photograph of a chimpanzee – conjoined with a human ear. This hybrid being is an early incarnation of the human animal that would recur throughout Bacon’s oeuvre. The chalky white figure emerges from a dark space possessing the shoulders and the disembodied ear of a man; there’s no human face, however, but rather the mouth of a chimpanzee, its thickly painted jaws jutting out of the canvas. The work is one of the series of six heads Bacon produced in the late 1940s for his first solo exhibition. Their characters are all enclosed within a cuboid structure that suggests a cage that isolates them and silences their screams. Indeed, the final work of that series, Head VI (1949) sees the artist sourcing directly from Velasquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (c. 1650) for the first of what would become 50 versions. The pontiff is reduced to an incarcerated animal, all divine authority negated.

Throughout this retrospective, animals of various kinds roam the canvases. Crucifixion (1933), despite its title, resembles a body on a cross more akin to an abattoir carcass. As the son of a horse breeder, Bacon would have been very aware of the viscerality of meat. In Man with Dog (1953), a forlorn white dog walks alongside its shadowy owner down a grey pavement as they pass a drain, a leash restricting its movement – a visual metaphor for the mundanity of life, perhaps. The mighty beast in Elephant Fording a River makes its way across the dark water, dwarfed by the landscape. Bacon’s preoccupation with human and animal movement led to paintings that saw people behaving like animals. A case in point is Paralytic Child Walking on All Fours (1961) in which the child, suffering from polio, awkwardly moves on her hands and feet as if imitating a monkey.

There are a number of rarely seen paintings from private collections on display, including Two Figures (1953). Here, Bacon has borrowed from Edweard Muybridge’s Human and Animal Locomotion photograph of wrestlers. By painting a white sheeted bed beneath them, the artist transforms them into a pair of lovers; placing them in a glass box, he suggests they are engaged in a voyeuristic display. Bacon was openly homosexual years before its legalisation in 1967 and both Two Figures and Two Figures in the Grass (1954) highlight the close proximity of violence and sex, particularly in the mind of a painter with sadomasochistic tendencies.

The 1960s bring an increasingly distorted human form. The figures became fleshier, suggesting butchered bodies, set against brightly coloured backgrounds. In Portrait of Henrietta Moraes on a Blue Couch (1965), the skin appears to have been flayed. Bacon’s stormy relationship with East End gangster George Dyer is seen here to have prompted some of his most powerful works. Three Figures in a Room (1964) sexualises Dyer as a reclining nude, whilst also portraying him astride a lavatory in a bluntly human moment. In the aftermath of his lover’s tragic suicide in 1971, Bacon painted a series of Black Triptychs, including Triptych August 1972, appearing at the Royal Academy. The outer two panels have Dyer seated in front of a black aperture, his body seemingly breaking up and melting away. In the centre panel, two figures engage in vigorous sex, on the verge of disappearing into the black void, immediately recalling the earlier wrestlers.

As this captivating blockbuster enters its final stages, one finds Bacon drawing on the bullfight and its metaphorical layers of eroticism, violence and life and death. He once remarked bullfighting was “like boxing – a marvellous aperitif for sex”. Sourcing images from bullfighting books and postcards of the corrida, he painted three canvases of the controversial tradition in 1969. In Study for Bullfight No 1 and Study for Bullfight No 2, the crowds enthusiastically urge on the matador and bull as they battle in a swirl of movement within a brightly coloured arena. Positioned above the crowd is a red flag resembling a Nazi eagle and swastika, the inclusion of the flag perhaps alluding to the crowd’s barbarity (the artist was known to have had an interest in Nazi imagery). Two decades later, in 1987, Bacon made a bullfighting triptych where the wounds of fragmenFeqted human figures are presented on screen-like forms next to an exhausted bull with visibly bloodied horns.

Bacon’s very last painting and the final work in the exhibition once again turns to the bull as its subject. Unusually monochrome it stands in contrast with the colourific intensity of his earlier corrida paintings. The animal is rendered one horn in the dark and the other in the light, stopping abruptly at an empty bullring, causing flicked-on dust to spurt up from the sand. Surely, it is a ready metaphor for the artist sensing his own impending demise.

This hotly anticipated exhibition, suffused with violence, is frequently bleak but endlessly arresting. One is assaulted on all sides by the twisted contortions of Bacon’s figures, be they human, animal or hybrid. Man and Beast brings into focus that animals were a pervasive sensibility in his art. Michael Peppiatt believes, “We are animals with a veneer of civilisation”, adding that Francis Bacon “was interested in that primal instinct.”

James White

Photos: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Francis Bacon: Man and Beast is at the Royal Academy of Arts from 29th January until 17th April 2022. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS