“I think cinema can be more than bedtime stories”: Andrew Dominik on 20 years of Chopper, working with Nick Cave and forthcoming Marilyn Monroe biopic Blonde

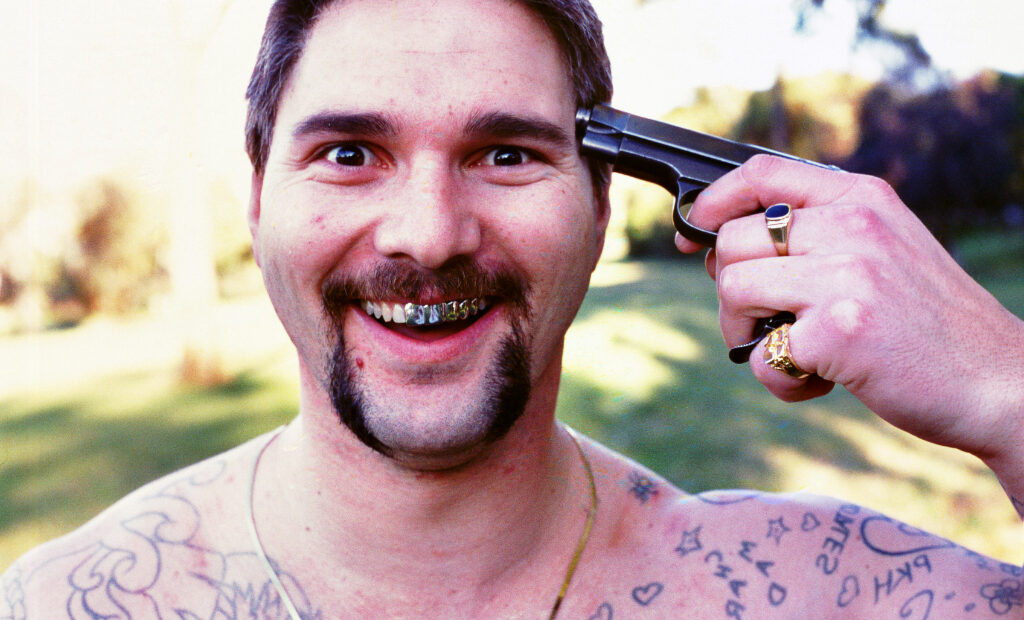

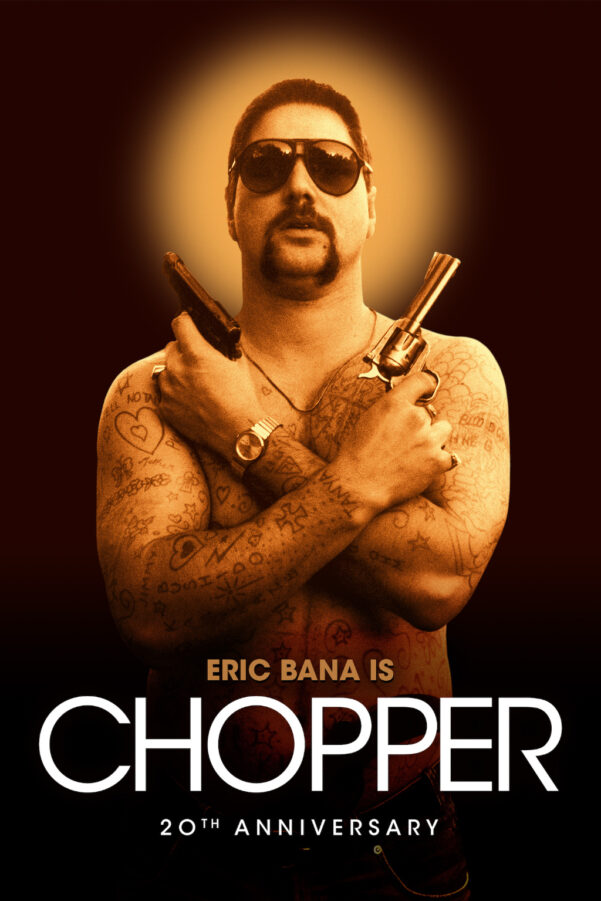

It’s been over 20 years now since Eric Bana’s career-making incarnation of the notorious Mark “Chopper” Read in writer/director Andrew Dominik’s feature debut hit screens. Based on Read’s own books, as well as Dominik’s extensive research and interviews with his subject, the film follows the exploits of the infamous Australian criminal from his time in and out of prison to stabbings to dabbling in drugs, presenting in graphic detail the brutal violence he perpetrated on others in a deadpan Tarantino-esque tone, while also conveying the man’s inescapable wit and charm, captured in iconic one-liners such as: “Keithy seems to done himself a mischief”.

It’s a visually stylish, fascinatingly disturbing, while also wickedly funny and nuanced portrayal of a larger-than-life character, held together with a powerhouse performance from Bana. What felt groundbreaking – and still does – is its manner of testing an audience in the push-pull of the empathy it garners with its unreliable narrator, stopping just short of glamourising or rationalising his extreme behaviour but offering an uncomfortable window into his perspective. Now the cult classic has been digitally remastered from the original 35mm print and will be back in cinemas once more to mark the anniversary.

In the wake of the film’s success, Dominik went on to make movies with Hollywood A-Lister Brad Pitt such as The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) and Killing Them Softly (2012). More recently he’s worked with Nick Cave on two documentaries exploring the musician’s grief and process of mourning after the death of his son, Arthur, in 2015, One More Time with Feeling and This Much I Know to Be True. On the horizon is also the hotly anticipated Marilyn Monroe biopic starring Ana de Armas, Blonde, based on Joyce Carol Oates’s 2000 book of the same name, already stirring controversy for some of its content, including a rape scene, which is mentioned in the book.

The Upcoming had the privilege of chatting with the filmmaker about revisiting his first film, his career since and his forthcoming projects ahead of the remastered Chopper landing in cinemas.

Hi Andrew! You must be absolutely thrilled that Chopper is coming back to cinemas and being re-released, remastered. How does it feel two decades on?

It feels like the film’s stood the test of time. See how it goes in theatres, right? I mean, they did something similar in Australia. But Covid, you know, just put the kibosh on all that. Like, it was supposed to come out, it was all primed and pumped, and then they locked the whole country down again. They’ve been a bit crazier over there, you know, than the English.

And have you had a chance to rewatch it yourself on the big screen?

Well, I regraded it, you know? I was the one who graded it.

Casting your mind back to when it was your feature debut, what was the initial inspiration or motivation to tell this guy’s story? Why was this the tale you wanted to put on the big screen for your first film?

Well, there was a certain practicality to it. Like, the books had come out, and everyone was reading them. Everyone was excited by them. And it seemed like the kind of film that would get made, you know? Like, you’re thinking about that when you’re like – whatever age I was, I can’t remember how old I was – like, mid-20s. And he was funny – that was sort of the initial thing. I mean, obviously, as I spent seven years thinking about the guy, doing research into his life and talking to people he knew and all that sort of stuff, you know, my involvement with it got a lot deeper. I had a photo of Mark where he’s naked, and he’s holding a glass of wine and smoking a cigarette, and he just had the most pained expression on his face. You can just look at him, and you can just see this is a person that’s in extreme pain, you know? As, of course, you must be to behave the way he did.

How did you see him as a person? Was there a process of getting to know him before you decided how you were going to portray him on-screen? He wanted to put out a perception to the world of being this kind of Robin Hood character, but there was more going on than that in reality. How did you see him and how did you amalgamate all the information you had, both from him and from other sources, to put this character on the screen?

Well, I just basically had to make sense of a lot of contradictory behaviour that was actually recorded by people who have investigated his life professionally, – you know, internal services unit cops – and there were hand-up briefs of all the behaviour that I could look at and read. All I did was try to make sense of Mark’s behaviour – and it did make sense. It makes a kind of sense, you know? Mark only hurts those he’s hurt before; I think Mark suffers from a fear of retribution; I think that once he actually gets attacked, he sort of relaxes. And I don’t think Mark feels too well with his own guilt feelings. I think that if he’s hurt you in the past, he’s probably gonna hurt you again – as a way to kind of head you off of the pass, you know?

And Eric Bana – this role kind of made him, in terms of his career and what came after. But it must have been a bit of a leap of faith for you at the time. Were you surprised at just how uncanny his performance was?

Totally. I mean, Mark had suggested him. I thought it was a fucking joke. The producer got the casting agent to get Eric to come in and read, and he did a great audition, but it was a little bit big. And I just went out of Melbourne and spent a day with him trying to work on it, and by the end of the day, it was clear he was going to be Mark – you know what I mean? And I think, at that point, I felt lucky to have found him. I don’t think anybody else could have played that part.

What do you remember from the shoot? It goes to some really dark places, there is a lot of violence – what were some of the highlights but also maybe some of the most challenging moments during filming?

I mean, the best moments were the ones that happened easily, you know? The first week we shot the best and the worst stuff. By that weekend I had… half the movie was this Carry On film and the other half was this fucking amazing film, you know? And I had to work out how to get rid of the Carry On stuff and keep the amazing stuff. But it was at that point that I stopped trying to be a good director, like, a responsible director, and I would just work until – shoot until I liked what I saw. And I didn’t care what anyone else thought about how I was going about it, you know?

In terms of the depiction of violence, what kind of role do you think that has in terms of the way it can shock an audience or cause the audience to have sympathy or not have sympathy for him as a character? And in general, what do you think the role of displaying violence in cinema is?

I think it’s amazing how quickly the audience can recover their sympathy for him, you know? I mean, probably the most upsetting thing he does is when he beats up his girlfriend and her mother. And it’s amazing how quickly the audience… I mean, you could feel that at the time, people being disturbed by that. You know what I mean? Violence towards someone who’s basically helpless – but they forgive him almost immediately. The charm goes a long way. But, yeah, I mean, the idea is to create a kind of push-pull. And I remember the first time seeing the finished film with an audience and he stabs Keithy in the face and then he’s almost in tears, “I’ll bring him a cigarette,” like, five minutes later. It turns on a dime like that. And you can really feel the bottom drop out of the room; you can feel that people just didn’t know where they were. And I thought, “Ah, okay, it works”.

Do you think that’s what cinema can do: test people in that way, and make them come out of the experience with a perception of yourself and the world that feels a little different?

I think most people go to the movies to have their ideas confirmed, not challenged. I’m just trying to think if a movie ever changed my mind about something. I mean, it can illuminate things that are within you, right? Has a movie ever changed your mind about something?

I don’t know. I did watch recently One Year, One Night about the Bataclan attacks in France. And it’s really, really visceral and really makes you feel like you’re there. And I remember while I was watching it thinking, “This is over the top”. But when I walked out of the cinema afterwards, in fact, I thought, “Oh, I really do feel like I’ve just experienced something,” and I thought that is quite an incredible thing that cinema can do.

Yeah. But I’m not sure that it changes your mind about anything – changes your life. I think that people go to the movies to have their ideas confirmed.

And on that note, what did you hope people would take away from watching your film? Did that align with the reaction in the aftermath or in last two decades?

Well, I think Chopper‘s an interesting movie because it doesn’t condone his behaviour, I don’t think, and I don’t think it glamourises or glorifies him – like, he’s definitely a very fluid individual. But it is made with sympathy for him. I mean, my interest in it was what are the consequences of violence for the perpetrator of violence? You know, it’s easy to kind of like see what they are for the victim, but what’s it like for the guy who’s violent? He’s the problem. He’s the one that we have to understand and come to grips with: why does he do it? And how does it make him feel? And where’s he gonna wind up because of it? And that’s really what I went into the movie wanting to know.

He was unbelievably charming, which you really do capture. Did you have any favourites of the one-liners?

No, no, I didn’t. But I mean, I remember when Eric and I were down and we spent a weekend with him in Tasmania. It was so fucking stressful. I think I slept for three days afterwards. – three days straight. I mean, both Eric and I fell asleep on the plane, our adrenaline just dropped and we crashed, you know? I had like six, seven hours of videotape. And I could just put that into a machine and somebody would sit there and say, “What was it like?”. And I would put it on and they would sit there and watch the whole fucking thing. I mean, he was that compelling – just a talking head, you know? He’s got this way of making you feel like he’s doing you a favour by not killing you [laughs].

That’s definitely going to put you on edge! How did you feel when he died? Was that a strange moment for you?

It was really sad. Mark and I, we had a little bit of a relationship after the movie. Like, he’d call me up, give me pep talks about, “Go to Hollywood! Make a movie!” – you know, that kind of stuff. I had a lot of affection for Mark. He got together with his girlfriend from the 80s, back together with her, and she hated the movie, mainly because it portrays his relationship with another girl who wasn’t her, who he was seeing at the same time. And to keep the peace, I think Mark sort of turned on the film at that point. But apparently, whenever… I know some people who made a documentary with him, and whenever she would leave the room he would put the movie on and show it to them. You know, “This is when I did that, that’s when I did this”, that kind of thing.

Talking about him giving you pep talks, Chopper set off Eric Bana’s career but also really put you on the map in a way that you hadn’t been previously, allowing you to do follow up films with bigger budgets and work with the likes of Brad Pitt. What do you feel it did for your work as a director?

Well, it got me in the door, mate. Chopper got a lot of attention in Hollywood, particularly from male actors, and those kinds of actors have a sort of list of pre-approved directors and it’d be like nine famous directors and me. You know what I mean? Then people were always trying to get me to do big movies with movie stars, and they’d start with me because they figured, “We don’t know this guy. He’s gonna be the easiest one to get” – you know? But, I never wanted to do those films. So it was amazing, mate. Brad Pitt’s really given me my career – without that guy, I’d be fucked. I mean he’s just, basically taken me under his wing, and done the best he can for me. But I’m like a terminal patient: there’s only so much you can do with me.

You’ve done so many interesting things since, and very recently worked with Nick Cave on a second documentary that played this year at Berlin Film Festival. Plus you’ve been working on this incredible new film, the Marilyn Monroe biopic with Ana de Armas, Blonde. Can you talk a little bit about those projects?

I mean, Blonde is just amazing. It’s the movie that I’ve always wanted to do, and I finally got to do it. And I didn’t fuck it up – it’s amazing.

Is Ana everything you would expect her to be?

Mate, it leaves people shaking, like they’re orphan rhesus monkeys in the snow. It’s like Raging Bull and Citizen Kane had a baby daughter.

And it doesn’t shy away, I believe, from controversial elements?

No! No, it doesn’t shy away from anything.

Has that made it harder to get it through to the screen?

Oh yeah, of course, totally. It was finished a year ago, we’ve just been arguing about what it should be and all that sort of stuff. But you know, it is what it is – nothing you can do about it.

As we’re in the post #me-too era, it’s more important than ever that you kind of don’t shy away from the ugly bits of these stories?

You’re preaching to the choir! Yeah, it’s a beauty.

Are there other filmmakers that you see doing great stuff at the moment? You’ve said you’re slightly disillusioned with the way cinema is right now.

Oh look, I don’t know. I’m just going through a period of not watching movies, you know? All I watch are Doja Cat videos. I love Doja Cat.

Do you look back though to the past as a golden age for cinema? Who were your big influences and idols?

Yeah, I mean, I think at the moment, my favourite is probably Fellini – like, fantasy Fellini, you know? 8 1/2 and onwards. I mean, that guy made a movie with his wife and his mistress. He must have been one charming motherfucker to get away with that. He’s got to be the best director ever if he could do that, right?

Indeed! Can you tell us what you might be working on beyond Blonde – or are you going to wait until this one gets the green light before you start thinking about that?

I’ve got a few ideas. But honestly, I’ve been sitting in a cutting room for like two years and now I’m just trying to get out in the sun, try and get back in shape, you know? I’ve got three movies coming out this year in theatres. I’ve got the re-release of Chopper, I’ve got the Nick Cave film in May and then Blonde, whenever the fuck Blonde comes out.

It must have been incredible working with Nick Cave – such an amazing musician and such an amazing guy – particularly on such a delicate subject?

Oh, it’s great, mate. I mean, yeah, I love Nick, Nick loves me. We have these sort of playdates – I mean, the last one wasn’t much of a playdate, it was a fucking trauma – at least for him it was. This one’s amazing because it’s sort of… it’s very simple. But it’s like, what has he learned? It’s five years later, he’s integrated the whole loss into the rest of his life and he has recovered from it. It’s not to say that he wouldn’t undo it if he could or that he doesn’t feel pain about it. But Nick has basically worked incredibly hard to to deal with the loss of Arthur in the most responsible way that he can, and it’s paid amazing dividends for all of them. And this movie, he explains what he’s learned. He wants to pass it on because we’re all going to lose everything at some point. How old are you?

36.

36, you’re still young dude. You don’t even know. I’m 54 and I’m telling you: death is coming.

Thanks for the heads up! Do you have hope for the future of cinema if you’re feeling like a bit uninspired by it right now? Do you think platforms like Netflix can help revive it?

I think there’s a lot of great TV. I mean, who knows, dude. I just think cinema has so many more possibilities than just the sort of “hero’s journey”-type story, you know? American movies, they’re just making the same movie over and over again. And it’s like reading Goodnight Moon – like when you’re a little kid and you had your favourite storybook, and I’m having it read and I’m having it read exactly how I’m used to hearing it because that’s the only way I’m going to be able to get rid of my anxiety and go to sleep. And I think cinema can be more than bedtime stories, you know?

We hear that you don’t trust heroes in general.

Yeah, totally. I mean, they’re boring. Having said that, there are real heroes in the world, I just haven’t made a film about one yet. I’m thinking about doing that – well, actually, I have: I’ve made films about Nick, and he’s a hero. And so is Warren. Fucking heroes, mate, both of them.

Sarah Bradbury

Chopper is re-released in cinemas and on digital on 25th March 2022.

Watch the trailer for Chopper here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS