“It’s about the crimes committed by the human body against itself”: David Cronenberg on Crimes of the Future, working with Viggo Mortensen and Léa Seydoux

In David Cronenberg’s upcoming film, Crimes of the Future, which will be presented this month at Cannes Film Festival, human species adapts to a synthetic environment and the body undergoes new transformations and mutations. With his partner Caprice (Léa Seydoux), celebrity performance artist Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen) publicly showcases the metamorphosis of his organs in avantgarde performances. Timlin (Kristen Stewart), an investigator from the National Organ Registry, obsessively tracks their movements, which is when a mysterious group is revealed. Their mission is to use Saul’s notoriety to shed light on the next phase of human evolution. The visionary Canadian film director talks about a project that started over 20 years ago, his fascination for the human body, working almost telepathically with Viggo Mortensen and Carol Spier, and how Athens made for the perfect setting for this story.

What is Crimes of The Future about?

In 1966 I saw a Danish movie called Sult which means hunger in Danish, and it was based on a famous Danish novel by Knut Hamsun, which was directed by Henning Carlsen. In that movie Per Oscarsson plays a poet, a sort of a broken, unrecognised poet who wanders the streets and has adventures and tries to create himself as a legitimate poet, literary force. At one point he’s on a bridge and he’s scribbling something in a pad that he carries with him, and you have a close up of it and it says “crimes of the future”, and that really struck me. I thought, I want to read that poem. Of course, he never writes it, but later I thought, well now that I’m starting to become a filmmaker I think I would like to see the movie Crimes of the Future, and so in 1970 I made an underground film, very low budget to say the least, called Crimes of the Future. The title really provoked me, and I think that 1970 low-budget, sort of underground film didn’t ever really satisfy all of the things that I thought could come out of that poem that never got written and so here we are many years later – like half a century maybe – and I’ve made another movie called Crimes of the Future, and the only thing the two films have in common is that they are technically about “crimes of the future.” The idea then being that as technology changes, as society changes, things that didn’t exist have come into existence and are suppressed for various reasons as being dangerous to society or a threat to whatever social structure exists: hence crimes of the future. I start to think about the human body because I have always thought that was what we are. The human condition is the human body, so Crimes of the Future could involve crimes that come out of what is happening to the human body… as it does evolve, it is changing, it’s changing in very subtle ways and then some not so subtle ways. Partly it’s because of what we’re doing to the planet, partly it’s what we’re doing to ourselves with our own technology and so that intrigued me. I thought I’d like to now make a movie that has to do with how society would react to changes in the human body that it thought were dangerous, were considered dangerous and should be suppressed. I thought that was an interesting topic for me to explore and that therefore is what the movie is about.

What’s the short answer?

I’d say Crimes of the Future is about the crimes committed by the human body against itself, and I know that that’s kind of mysterious and kind of confusing but that’s my answer to that question.

What compels you to look at things that scare a lot of people especially now?

I think there are a lot of cases that one can refer to of people embracing their disease, a disease they have, a disability that they have, a mutation that they have, it’s part of a human desire to make something good out of whatever the human condition offers, and so I think Saul Tenser is just a sort of an exaggerated, extreme version of that. He has found himself producing new organs in his body or things that would be considered tumours. In this case they seem to have an organisation that a tumour does not have. A tumour is really a kind of random collection of cells that grow uncontrollably, they do disrupt all kinds of things in the human body but to no apparent purpose, and they’re basically just destructive. In this case he’s creating new organs that seem to have a function, we just don’t know what that function is, and so it’s a strange kind of designer cancer as one of the characters calls it. His goal is to incorporate it into his life, not to deny it, not to just destroy it but to make it something. In his case, he’s making performance art out of these tumours and, with his partner, designs a series of performances which involve the exposure of these organs and a removal of the organs as though they are art creations that his body has undertaken on its own. It’s partly a desire to come to grips with the reality of his own body, so it’s a need in our human condition that our bodies are constantly changing and require adjustments by us – philosophically, emotionally – to deal with those changes. So, this is a sort of more structured exaggerated version of what Saul Tenser is undergoing.

Do you think that could happen with our organs?

Oh I think we’re doing it, I think we’re definitely changing, I don’t think there’s any doubt about it, it might not be as obvious as I have depicted it. A famous Nobel prize winner, Gerald Edelmen, said that the human brain is not at all like a computer. It is much more like a rainforest where there’s a constant striving for dominance amongst the neurons and the different elements in the brain and they’re constantly responding to the environment, that is to say the intake from your eyes, from your nose, from your senses and also how much you exercise it. So even just talking about the brain as the super organ of human existence, it is constantly changing and mutating and so it’s not much of a stretch of the imagination to imagine that for other parts of the body. The digestive system responds, we now understand the microbiome in the human gut and the intestines, that it’s actually a lot of living organisms there that communicate with the human brain. There’s a constant connection these things would be considered science fiction years ago, and now are just understood as part of what the complexity of the human body is. So, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration really, I think it’s just a sort of extrapolation into the future that I’m undertaking with this movie.

Why is now the time to do this film?

Well, I wrote this script for Crimes of the Future in around 1998, 99, so it’s over 20 years old and there were a couple of attempts to get it made and for various reasons it didn’t get financed. That happens, that’s not unusual, but it was only when the producer Robert Lantos phoned me and said: ”You know, have you looked at your old scripts?” And I said: “Because of its science-fiction technology core, I’m sure it’s completely irrelevant now.” And he said: “No, you should re-read it, it’s more relevant than ever.” I thought that’s a good line, and I read it and I thought he was right. I’ve never been much for prophecy, I don’t think of art as being prophetic, but you can anticipate some things almost by accident, especially when you’re writing something that is basically science-fiction as this movie is. You stumble upon something that has a trajectory to the future, and this story did have that and it was still pretty valid. I think people are more aware now, for example, of the toxicity of the environment that we are creating on Earth and how we are in some ways destroying the Earth, we’re certainly altering it, there’s no question about that. To see how the idea that technology is really the extension of the human body, and the human will… there was a time when people thought that technology could be inhuman, and for me technology was always a human thing. I think in fact it’s a reflection, it’s a mirror that reflects back to us what we are, the good parts and the bad parts, the destructive parts and the excitingly creative humane parts so there is that element in this movie that talks about the reflection of what we are in technology.

How does this fit into your body of work?

I don’t really think about my larger work, honestly, I mean each project for me is a separate thing and I know that there will be connections amongst the films whether I’ve written them myself or they’re an adaptation or whether they’re based on a play or a novel. I know that because I’m interested enough to turn it into a movie which is a huge endeavour. It takes a lot of time and will and energy, that there will be connections amongst these that have to do with my sensibility, but that’s as far as I go.

Do you have a preference to filming your own work or adapting someone else’s?

Once I have a script that I have committed to, and the production and so on, they’re all the same. I mean, there’s no difference between my script and somebody else’s, in fact I’m just as hard on my own script as I would be on somebody else’s. In the editing room, after shooting the movie, I’m pretty brutal. They have to stop me from creating a 72-minute movie, you know I’m in the odd position often of having producers begging me to put stuff back in. I like to cut, it’s fun to see how lean you can be with it and still have the movie work.

What was it like working with your old friend Viggo Mortensen?

Well, Viggo and I, we have a long-term relationship and we’re also friends. We know each other very well and we’ve spent a lot of time together aside from movie making. So, at the same time we’re both perfectionists up to a point and when it comes to work we’re working as an actor-director relationship, but we do have a second hand. We do have a sort of a telepathic kind of understanding of each other because we’ve worked together so many times. I mean, he is a director himself, he’s a screenwriter, a musician, a poet, a publisher and so he approaches movie-making that way. In other words, he’s not shy about commenting on the script even if it’s a scene that he, as his character is not in, and that’s unusual, not too many actors do that.

Why was he the right person to play Saul?

Well, now, the fact that Viggo and I are friends and I think he’s a fabulous actor with his huge range still doesn’t mean that you can cast him in any role and that would be correct for him. It’s the same when he reads a script, even if it’s from me, a friend. It doesn’t mean that it’s a no-brainer and he will do the movie. It has to be something that works for him. As I say, ultimately casting is a black art, it’s a very mysterious thing. Once you’ve made the movie, if you’ve done it right, it’s almost impossible to see any other actor in that role.

Can you talk about Léa Seydoux?

I originally offered the role of Timlin to Léa Seydoux. I had seen her in quite a few movies and was

interested in her as an actress, and the structure of the movie was such that that role, several of the roles, could be played by actresses or actors who had accents because they were either Greek or an African actor – like Welket had an accent from his country and the movie would support that. That was exciting to me because the language, the dialogue is very important in the movie despite the fact that it has special effects and so on… the dialogue is really quite critical. There’s a lot of talking in the movie, so Léa with a French accent, I was thinking that she would be a really beautiful textural addition to the movie. At a certain point we were talking to certain other actresses about playing the role of Caprice, who is Tenser’s performance partner and in some ways lover – it’s ambiguous in the film. After Léa read the script, she was very excited to be in it and to work with me she said: “You know I’d really like to play Caprice.” After I thought about it for a while, I thought, you know, that’s actually a great idea, so I changed my mind and Léa plays Caprice and Kristen Stewart plays Timlin. The dynamic between those two is really very interesting because obviously they’re very different, they come from very different places, they’re about the same age but Kristin’s very LA American and Léa is very Parisian French. You want an interesting dynamic, you want an interesting chemistry amongst your actors, and that’s part of the art of casting, is not just one person who is playing the lead. To my non-surprise, Léa brought a great acting intelligence and culture to the role, along with an incredible emotional sense that I knew she would bring. It really transforms the character of Caprice. She’s still saying the same dialogue that was in the original script, but coming from Léa it has a depth and an emotional impact that other actresses would not have brought, they may have brought something else but not that, so it was very exciting working with her. She’s just a delight to work with.

Why did you make this such an ambiguous place with diverse people there?

I mean part of it comes from my living in Toronto, which has been multi-cultural since I can remember. Being born in 1943, you have to understand, and in a section of Toronto that became Italian but before that had been Jewish. So, to me, the globalism that is much discussed either as a good thing or a bad thing it’s happening, it’s inevitable. Part of that is the internet of course, the connections amongst people, it’s a huge change that you can be on social media and connect with people all over the world instantaneously. The cultures are interpenetrating each other and so my anticipation of any world of the future, but really as now is exactly this: that it should be not without its own unique individual character. Globalism is becoming one bland simple thing, it’s not at all, it’s really quite complex and it’s constantly shifting and changing much like the human brain, so that was the feel that I wanted the movie to have. Though I wrote it thinking about shooting in Toronto, I still was suggesting this kind of alternate reality that became much more particular when we decided that we would shoot the film in Athens, Greece. I really embraced the textures of Athens and the graffiti and the streets and the ocean rather than try to fight it and make it be more like Toronto. I wanted it to be exactly like what it was. I visited Athens in late 1965 so as you know, half a century later, I’m back in Athens, it has of course changed a lot, but at the same time, it is an ancient city and so much of it is the same. It’s very exciting to do that, and I found it really stimulating to be working there. It really helped create the feel of the interiority of this movie and the city in the movie.

Did shooting during Covid add to the experience considering the topic of the movie?

Well shooting a movie during the era of Covid in itself is an incredibly interesting experience. I did some acting in a couple of things, Star Trek: Discovery and also Slasher, a Canadian series, and I was interested to act in those because I was anticipating making Crimes of the Future. Those two TV shows were being shot under Covid protocol, so wearing masks, having constant tests, keeping social distancing and still making a movie, which is a very social experience, was revealing to me because I could see that it was possible to do and that you would sort of get used to the rhythm of that and it wouldn’t hurt your filmmaking. There was that and then of course there was the environmental disaster that continues, climate change which was causing forest fires in British Columbia and Canada, but was also causing forest fires in many places in Europe including Athens. The forests that were in the north and the south of the city of Athens were on fire one morning, I woke up and I looked out my hotel window and I couldn’t see anything, it was like total smoke… It was very scary. We managed to continue shooting and, in a way, it just confirmed the reality – let’s say the philosophy – of the movie we were making. That things are changing, they’re mutating, inside the human body as well as outside the human body. Just, the validity of the movie philosophically… of course it’s entertainment, but part of the entertainment is that it has a resonance with people.

How do you view the future now versus when you started your career?

The future? I have less of it. At 78 I have less of a future than I had before, but I have often said that philosophically I’m an existentialist. I really think of myself that way, and part of the understanding that existentialism gives you as a philosophy is that we are constantly referring things to the future, we’re constantly looking to the future, and that is part of what keeps us going and keeps us sane. At the same time, it can prevent us from living in the present fully, we’re constantly anticipating what will happen, and so I try to do both in the films. I feel that movies are not really predictive, I mean they’re not prophetic, in some science fiction it is – science fiction writers, like Arthur C Clarke. For him it was a triumph that he predicted satellites and satellite communication. To him, that would fulfil some of what his writing was about. For me, that’s not my game, it’s more to understand what the human condition is now, and it can sometimes be illuminated by trying to see where we’ll go. Looking at the human condition and, and all its glory, and its many phases and trying to understand what it is to be alive is a crucial thing if you’re an existentialist. It’s like I’m at the seashore and I’m picking up seashells and I’m saying: “Whoa look at this one, this is really incredible, how did this creature create this thing?” I don’t have the answers to anything, but I have the curiosity to look at things that other people don’t have time to look at, and I have the time to do that so that’s what I’m giving them.

Can you talk about working with Carol Spier and the various creations?

One of the fun things about creating technology that doesn’t actually exist is designing the technology and anticipating how it might work and how it might not work. That’s really fun for me, it’s always there that filmmaking is a very childlike event, you’re like kids in a sandbox, you know and you’re dressing up in funny clothes and you’re putting on a moustache and you’re talking with a funny accent and you’re pretending to be people that you’re not. It’s very childlike, and you can get very serious and professional and all of those things about it, and you might lose sight of that childlike joy of creation, but it’s a mistake if you do. You really can tell which filmmakers are still in touch with that, and I am in touch with that. I think undoubtedly there are connections between those effects that we have created physically and effects from movies in my past because it’s always the body that is the centre of these things for me, and that is because, as I say, it’s easy to lose sight of what we are physically. So, to emphasise that my feeling that technology is the human body, it comes from the human body, the technology that I tend to create in my films when I’m doing this as I’ve done on Videodrome or Existenz, tends to be very body-based, looks very organic, looks very physical, looks like it grew from cells. That is the designs that we have done for Crimes of the Future, and working once again with Carol Spier. So, given the designs that I was anticipating, which were described to some extent in the script, it was exciting to get to work with Carol Spier again. We literally have been working with each other for half a century and, and once again as with Viggo, you have a collaborator with Carol, a collaboration that’s gone on much longer, so there is a shorthand and a telepathy. To make real these things that in the script were just sort of suggestions of shapes and forms, Carol, as usual, finds collaborators in her art department who can realise these things for us both. One of the liberating aspects for me is my attitude towards my script as though it’s just a suggestion, it’s not like the Bible where it must be accurate, it’s not like Shakespeare. It is a process, and so there were suggestions in the script, for example there are performance artists who base their performances on their bodies in the script as was the case 20 years ago when I wrote the movie. That also held true for the very special bed where the lead character, played by Viggo, Saul Tenser, sleeps in, because he has to have the bed constantly moving in his sleep because he’s experiencing pain, but the bed is so plugged into him that it can anticipate these painful episodes, and move him in order to alleviate the pain. There’s a chair that does the same thing for him because he has eating problems, and he has to be moved around constantly so that he can eat. The designs for these that I suggested in the script were simplistic, very mechanical, and in design terms we ended up going much further with very organic and flesh like and bone like creations. These were designs that evolved over many months of discussion and attempts to make what was in the script work as it was written, and then could see it really wasn’t that effective when you try to make it physical, when you actually make the devices. It is also something exciting to do physically as opposed to with just visual effects. I mean, these days, and it’s been this way for quite a long time, computer effects, CGI, computer-generated imagery are great tools, but when it’s overused you get the feeling that things are kind of cartoon-like. When they’re used in conjunction with physical effects that are actually there, that is for me the beauty of visuals effects, that you can really anticipate them on the set, you can add things so it’s a combination of physical effects, prosthetics that are applied to actors’ bodies. Then CG effects add things to it that you couldn’t do physically and the combination can be really very powerful, and we certainly went quite far with that in Crimes of the Future.

The editorial unit

Photos: Courtesy of Neon

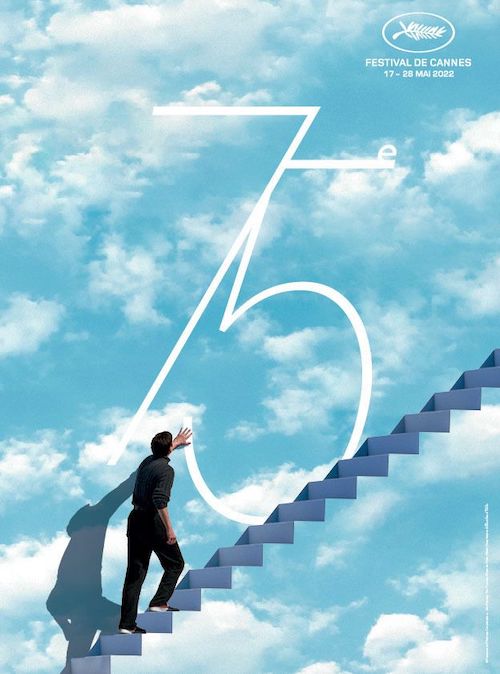

Crimes of the Future is presented at Cannes Film Festival 2022 as part of the official competition, the interview is part of the press pack.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS