“My aim is that the film is smart enough on the one hand to allow itself to be totally idiotic on the other”: Michel Hazanavicius on zombie movie Final Cut (Coupez!)

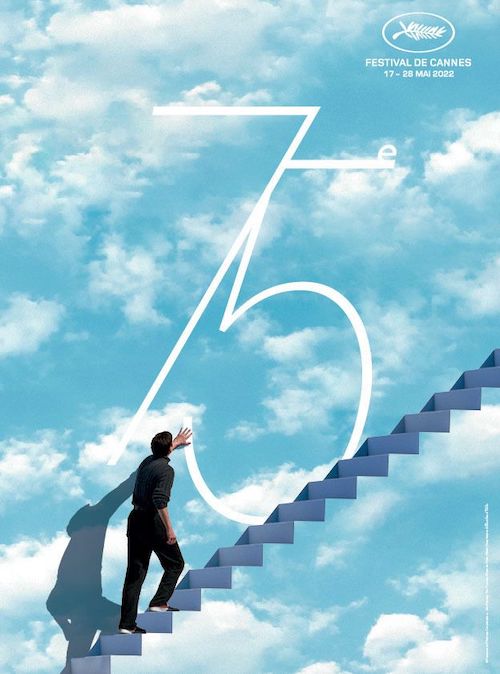

Final Cut (Coupez!) is the opening film of the 2022 edition of the Cannes Film Festival. Presented out of competition, it’s a high concept movie with a catastrophic start that quickly takes a detour and ends in a completely unexpected manner. Director Michel Hazanavicius talks about how he came up with the idea for this picture and why he chose Bérénice Béjo and Romain Duris for the leading roles.

What were the origins of Final Cut?

I’ve wanted to write a comedy about a film shoot for a long time. As long as I’ve been directing, I’ve had the opportunity to observe a lot of funny behaviour and have experienced a lot of shoots – sometimes amazing, sometimes ludicrous, sometimes touching. I like this basic material: a film set, which is a kind of slightly exaggerated micro-society, in which the characters often reveal themselves in a spectacular way. So, I got into it during the first lockdown, started making notes and working on a story that revolved around the idea of a long single take. Then, quite by chance, I talked about it to Vincent Maraval, who was very happy to hear that I was interested in this subject, and told me that his company had just acquired the rights to One Cut of the Dead, a 2017 Japanese student film that is absolutely connected to what I was telling him about. I watched the film and thought it was really good, with a brilliant structural concept. I told Vincent and Noëmie Devide – who had discovered the original at a festival – that I was up for a remake. Final Cut is the remake of Shin’ichirō Ueda’s film, itself an adaptation of the play Ghost in the Box.

Are you a fan of gore, of Z movies?

Not really. I watched quite a few at one stage because I thought they were funny, but I can’t really say I’m a fan. On the other hand, I like the idea that a director makes a film no matter what, with or without a budget – that what matters is doing, making. I find this approach not only brave but, above all, beautiful. In this genre, Tim Burton’s Ed Wood is a real achievement. Aside from that, I did watch quite a lot of zombie films and series for Final Cut and rewatched all of George Romero’s movies. Perhaps the main set recalls the shopping mall in Dawn of the Dead (1978). My film isn’t really a zombie movie at all, it’s no Train to Busan…

Yet in your film you never look down on the genre…

No, not at all. In fact, for me, reinterpretation only works if there is respect and tenderness for the reappropriated work; that’s what makes it even more interesting and multidimensional. Without it, you can quickly fall into mockery, even sneering. It’s often a fine line, but I need a solid first degree for there to be a second degree. There’s always a real story behind anything funny, and I need to be in tune with that story.

Is it a tribute, like the OSS 117 films might have been?

Yes and no. The OSS 117 films were pastiche, pure and simple; the characters are stereotypes and have no reality. In that sense, there’s a relationship with the first part of Final Cut. It’s true that it’s fun to take well identified pieces of filmmaking and play with them, to create a dynamic between the memory we have of these films and whatever I’m suggesting. It’s a fertile device. That’s the principle behind La Classe Américaine as well as The Artist and Redoubtable. To return to your question, yes, this is a tribute to DIY films, to no-budget movies made with more energy than money, but the film is also, and perhaps above all, a tribute to the people who make films: actors and directors, but also technicians, trainees, everyone… a tribute to cinema as it’s being made, to the trade of cinema, day to day. This is where it differs from OSS 117, which certainly isn’t intended as a tribute to racist, uneducated, misogynist, homophobic and slightly anti-Semitic French.

Final Cut is first and foremost a comedy?

Yes, first and foremost, it’s a comedy, perhaps of a special sort, but it is really a big, fat comedy. I was very happy to return to comedy with Final Cut, as I did for OSS 117 and La Classe Américaine – films exclusively designed to make people laugh. We’re in that vein. There’s certainly a connection with The Artist and Redoubtable, which also dealt with cinema, but, in terms of tone, it’s nearer OSS 117 and La Classe Américaine. Moreover, in Final Cut there are several types of comedy, both completely absurd and more sophisticated stuff. In the structure itself, there’s the pastiche of the first part, the character and situation-based comedy of the second, and a more vaudeville third part, but I also wanted to situate a lot of different things – different types of laughs – within the scenes. I tried to make a rich, generous film, in which the viewer is involved. I always try to make films that can be watched over again, and I hope Final Cut is one of them. In any case, I think it works very well on at least a second viewing. Basically, I not only advise you to see it, but I recommend you go back and see it again. Several times if possible. And with other people.

You cast the Japanese actress who played the producer in One Cut of the Dead. Is your film faithful to the original version?

Yes and no. I have betrayed it as much as possible in order to be as faithful as I could, because I’m convinced that when you adapt you must betray. Of course, I’ve kept the structure and everything I liked, but I also tried to stay true to the energy of the original, shot in six days, with very little money. We worked on a different scale, for sure, but our film wasn’t very expensive either. It was shot in six weeks, with a budget of €4 million. As for the actress, Yoshiro Takehara, she’s incredible. She brings a madness that is not only joyful, but very useful narratively. You really can believe in a project like the one in the film emerging from the brain of a character like hers.

The film is punctuated by poetic lines like “Post-apocalyptic piece of shit!”, “Sayonara, one-armed ghoul!” and “Fucking zombies, I’ll rip all your assholes open!”.

Yes, indeed. My aim is that the film is smart enough on the one hand to allow itself to be totally idiotic on the other. The energy of the film lent itself to this, because it doesn’t boil down to just that – it’s richer. That’s why it seemed balanced to also go towards this kind of nonsense.

Gore and mockery sit alongside enormous love for these craftspeople of cinema.

Yes, that’s the idea. The characters struggle, they’re not particularly brilliant at first, and they face their problems, but at some point, they join forces and manage to get to the end. This is where they become heroes. The film they’re making is no masterpiece, but they’re making it; they get there, and that’s what’s important. You know, it’s hard to make a film – even a bad one. It’s tough. Sometimes critics tell us we’ve made a bad film, but that’s not how it goes. I have many director friends and I’ve never heard one of them say, “I’m making a dud right now.” We do the best we can every time. Sometimes we’re not at the top of our game, or we’re worried about money, or we don’t have the actor we wanted, or he doesn’t know his lines, or we get rain when we need sun… In short, we face a lot of problems and we don’t always overcome them; we can screw up. But at the same time, it can be a beautiful human adventure. Making films is always an ultra-fusional experience where, for six, eight, twelve weeks, we work together, we live together, and everyone does the best they can. The collective is stronger than the sum of individuals and the human adventure is sometimes more interesting or more beautiful than the object you’re making. And it isn’t necessarily such a big deal. That’s what this film is about.

Let’s talk about your cast. First of all, Romain Duris.

Romain Duris is an actor I love, and one of those actors who gets better with age. He’s handsome, very funny, and I’ve wanted to work with him for a long time. He is very generous. His character isn’t quite the white-face clown: he’s more complex, but he is surrounded by social misfits and Romain has the intelligence to leave room to his partners. He plays what there is to play without worrying about the result, or the fact that he’s the lead, and he doesn’t try to be funny. It’s a real delight for a director. He’s always spot-on, even if he is ready to follow you in directions he didn’t anticipate. It’s a real collaboration. And what’s more, he accepted the role in less than 24 hours – it’s a real pleasure to have an eager, enthusiastic actor. For that matter the film has generated pretty mind-blowing enthusiasm. When I called on actors, it was a “yes” practically right away. They were all delighted to take part in a comedy where they were going to be able to let go, a comedy with zombies, but also with characters they know best – cinema people.

You have a fantastic cast.

Yes, it’s a film with a lot of characters who are present almost all the time, and we were lucky to have a bunch of awesome actors available and all happy to be there. The list is long, and I loved working with all of them, so here we go: Finnegan Oldfield I’d spotted in Selfie and We Need Your Vote, and at the Césars where he had made a legendary joke the year I was there for Redoubtable. I offered him the role of the actor who’s a bit of a pain and he accepted immediately. A great encounter – he’s an actor who really works on his roles, who searches, who possesses a contagious energy, and was very happy to appear in a full-on comedy. As an actor he has a vitality I love… never limp. Same for Grérory Gadebois, with whom I’d already worked, and whom I really love. He, too, was very happy to be in a full-on comedy. He has such humanity… he’s not necessarily used to comedies, but he knows how to do everything. He’s hilarious in the film. Raphaël Quenard I saw in Mandibles by Quentin Dupieux, and in a short; he’s perfect in the role of an unpleasant character. There’s a kind of madness, and at the same time a freshness about him – he’s quite something. And then there’s Matilda Lutz, who we saw in Revenge and who was perfect for the role, both very pretty, as the character required, and with an understanding of the genre that allows her to shift and be very subtle in a comic setting. There’s also Sébastien Chassagne, a chameleon who also always manages to inject sincerity into comedy, even at full throttle. Jean-Pascal Zidi, an obvious comic powerhouse, manages to be funny with very little, but he is, above all, a marvellous actor: very precise and very intelligent. The same with Lyes Salem, a solid actor who doesn’t strive to be funny, who trusts situations and brings a real richness, a density. There’s also Agnès Hurstel, Luana Bairami and Raïka Hazavanicius, in small roles, but who bring their personalities, their modernity and give colour to the film. The film really benefited from their talent. And then there’s also my oldest daughter, Simone Hazanavicius, who plays the daughter of the director played by Romain Duris. It was very touching and satisfying to work with her, to rediscover my daughter as part of a shoot, to work with her sensibility, and with her as an actress – I loved the experience. She brings a very special touch to the film, which gives it an extra dimension.

And, of course, Bérénice Béjo. Was it difficult to convince her?

You know, there’s really nothing obvious about it. Each film is different, each character is different, there isn’t a law that says Bérénice will appear in all my films, or that she’ll accept everything I propose her. Besides, to be honest, for this one I said to myself at first that she wasn’t the character; I told her we wouldn’t be making this film together. I envisaged a tougher character, for an actress like Blanche Gardin, for example. Then I asked her to read the script. She liked it, and the way she liked it convinced me she would be excellent. In the end, she’s magnificent in the film. She’s an astonishing actress, with no gimmicks; she starts from scratch each time. She works a lot on her roles, not only physically, and arrives on set with enormous availability, which makes it possible to really work, explore, improve. She also brings a great humanity, she always respects the character, without looking for effects, which enriches the comedy. She’s one of those very good actors who can play many different characters and whom you just have to push a little bit to tip over into comedy. It’s always tricky to speak well of the person you love when promoting a film, because we are addressed as a couple, so there’s something shameless, which can come across as smugness. But here I’m talking about Bérénice Béjo the actress, so it’s all good. And since she started practising krav maga, I’d rather say only good things about her.

The film tells the story of a family, but it’s also a real family story. It’s pretty meta?

Really meta. My wife plays the director’s wife; my daughter plays her daughter. It’s in line with the subject, but the film is meta on many levels – it’s a constant mise en abyme. The shooting of a film in the film that itself tells the story of the shooting of a film, which is the remake of a Japanese film that tells the story of the remake of a Japanese film, actors playing actors, scenes viewed from multiple angles… even we got lost sometimes while shooting…

The challenge of the film is risky. There’s this first part that lasts about 30 minutes, then the reverse shot coming next, which explains everything and increases the laughter tenfold.

This was one of the problems of the original, where some viewers apparently switched off quite quickly. It’s difficult to make a film that must be perceived as a failure while remaining entertaining. Trying to cram in too many gags would have damaged the whole thing – it had to be a bad film, but to be satisfied with making a bad film is to risk making only that: a bad film. This film has a special structure that had to be respected.

Is the first part really one unbroken take?

It is a real 32-minute sequence shot, with one small editing point, that I had to do for technical reasons. But I was able to do it precisely because it was thought, shot and executed like a sequence shot. I’ve never been obsessed with the sequence shot like Gaspar Noé or Alfonso Cuarón. It’s never been my holy grail, even if it obviously often possesses a great narrative power. I have of course done some, but for comedy, I tend to cut in order to take the best of each shot, bring out the actors, master the pace, etc… Here we had to confront this exercise, with the added requirement that it appeared to have failed – while controlling the failure, of course, since it prepares the last part. So, I storyboarded the whole thing. All in all, I see this shot as 250 shots, connected by a single camera movement. We worked with the actors, we rehearsed it for five weeks out of the six of prep. The actors came on set every day, as did Jonathan Ricquebourg, the DP, who did the light and the framing. Things evolved, and I re-storyboarded, so that each movement, each camera placement, each timing was rehearsed and rehearsed again until everyone had integrated it. During the final week of prep, we worked with the grips, special effects, stunt people, makeup, wardrobe… We had fake blood, decapitations, characters turning into zombies with a few seconds for makeup changes, prosthetics, lenses, etc… We choreographed everything so the movement and timing would be as precise as possible.

In the end we shot it in four days, each time with the pleasure of accomplishing a performance. But the right take came on the afternoon of the fourth day. I must say that the whole crew was admirably united, and what we experienced was in a way not so far from what is related in the film. From Jonathan Ricquebourg, the talented young DP, to Julien Decoin the first assistant, through production designer Joan Le Boru, Vesna Peborde, the makeup artist, and hairdresser, Margo Blache, I was lucky to have a crew as solid as it was talented.

The director played by Romain Duris runs all the time. Is this what directors do?

Not necessarily, literally speaking, although on a shoot it’s certainly better to wear good shoes. There’s always the idea of urgency because, on a set, there’s a lot of people at work, and that means a lot of money. Time is expensive. And you need it to work – time. So metaphorically, yes, you’re constantly running – behind the film you’re hoping to make, and which is constantly escaping from you.

In Final Cut you’ve got your work cut out when it comes to problems: the sequence shot, the film within the film, interwoven stories, the meta aspect…

Yes, but they’re not necessarily problems, they’re more like playgrounds. That’s also what excites me about this job because I try never to make the same film twice. I like the idea of discovery, making a new film each time, trying to learn the rules of the game and its particular way of functioning.

Jean-Christophe Spadaccini, the great SFX maestro, took care of all the special effects and gore.

Yes, I’d worked with him before, and he’s incredibly good. The challenge for him was the performance aspect, but also keeping to the Final Cut spirit and finding dirt-cheap solutions that were nonetheless appropriate, with the right values in terms of narrative. For the sequence shot, it was like shooting live – there was no room for error. He was on-set with his crew. They threw blood by the gallon, they managed decapitations, effects – it was hilarious. There’s nothing digital in the film: everything was done on-set, trying to find the cheapest solutions – old school!

You called on Alexandre Desplat for the music.

He’s a great composer, he understands quickly; his analysis of the dramaturgy brings a lot to the film, a real sensitivity. And he’s very modest. When you tell him something isn’t working, he composes something else, with disconcerting ease. It’s almost irritating how everything seems so easy for him, from muzak to a real film score – including, of course, zombie movie music – everything is simple with him, he can do anything. I loved working with him.

During the end credits, you pay tribute to Bertrand Tavernier and Jean-Paul Belmondo, as well as thanking Quentin Dupieux.

Quentin has a small non-speaking part as the director of a film that doesn’t seem so great. I’d done some walk-ons in his films, so I asked him to do one for me. Tavernier and Belmondo, that’s something else. We owe them so much. Both meant a lot to me, in my life, the very fact that I’m making films, and probably the way I make them. Both left us during the making of this film and I wanted to give them a little sign. I loved them both very much.

Finally, are you happy with the film?

Extremely! There’s a lot in it and, paradoxically, even if it’s a remake, I see it as a very personal film. I’m very happy that Noëmie Devide, Brahim Chioua and Vincent Maraval have made it possible.

The editorial unit

Final Cut (Coupez!) is presented at Cannes Film Festival 2022 as part of the official competition, the interview is part of the press pack. Read our review here.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS