Feminine Power: The Divine to the Demonic at the British Museum

The British Museum is excelling itself at the moment with some thought-provoking exhibitions. Feminine Power: The Divine to the Demonic has been ten years in the assembling by curator Belinda Crerar, and includes over 80 artefacts spanning 8,000 years and six continents. Most are from the museum’s collection, though many are rarely displayed, some are on loan and one, a statue of Hindu goddess Kali, has been specially commissioned. Incredibly, this is the first major exhibition to explore female spiritual beings in world beliefs and mythological traditions.

In this meticulously researched show, there are examples of male and female Japanese Shinto creation spirits who stirred the primordial water with a bejewelled spear to create land; there is a grotesque mask used in Bolivia to dance about in to scare off Satan (it ought to do it); there is a classical statue of Hekate, the Greek goddess of witchcraft, portrayed in triplicate, an insouciant look on one of her marble faces; there is a representation of the Virgin of Guadalupe in neon straw from 1980s Mexico. Some artefacts are genuinely terrifying: Kuashik Ghosh’s statue of Kali wears a garland of severed male heads and seems pretty happy about it. We learn that this is a metaphor for her power to destroy ego. Kali is still actively worshipped and feared, thus this depiction of her was welcomed after a long flight with a ceremony and some vegetable sacrifices to appease her.

The display is dense with information – a lot to take in and assimilate in the mind. It successfully and delicately picks apart myths we have lived with and absorbed, whether consciously or not. The deceptively simple descriptions impart a lot of information.

The creation and nature goddesses are phenomenal. A sculpture of Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes, is made from the red wood that grows first after an eruption. Pele is said to have flaming red hair and a fierce temper – one of her many forms is lava, a destructive force that also creates new life after its fiery eruption. She is depicted with a garland of flowers round her head and a no-nonsense expression.

One of the most powerful artefacts is a sculpture of Egyptian goddess Sekhmet with a lioness’s head, a ferocious deity sent by her father, the sun god Ra, to destroy mankind. After regretting what he had unleashed, Ra subdued her with beer dyed red to look like blood, after which she was able to control her rage to bring healing, becoming the mistress of life. A statue from around 1370 BC still exudes a coolness from the stone, even after thousands of years. She is presented standing, holding a papyrus staff and an ankh, and there is something lifelike in the stance, how she holds her arms, something almost imperceptibly but unmistakably feminine. This artefact is powerful and gives off an air that its subject is not to be messed with, perhaps more so than any other of the myriad terrifying and fascinating objects here. All these ferocious she-gods bring to mind the Samuel Johnson quote: “Nature has given women so much power that the law has very wisely given them little.”

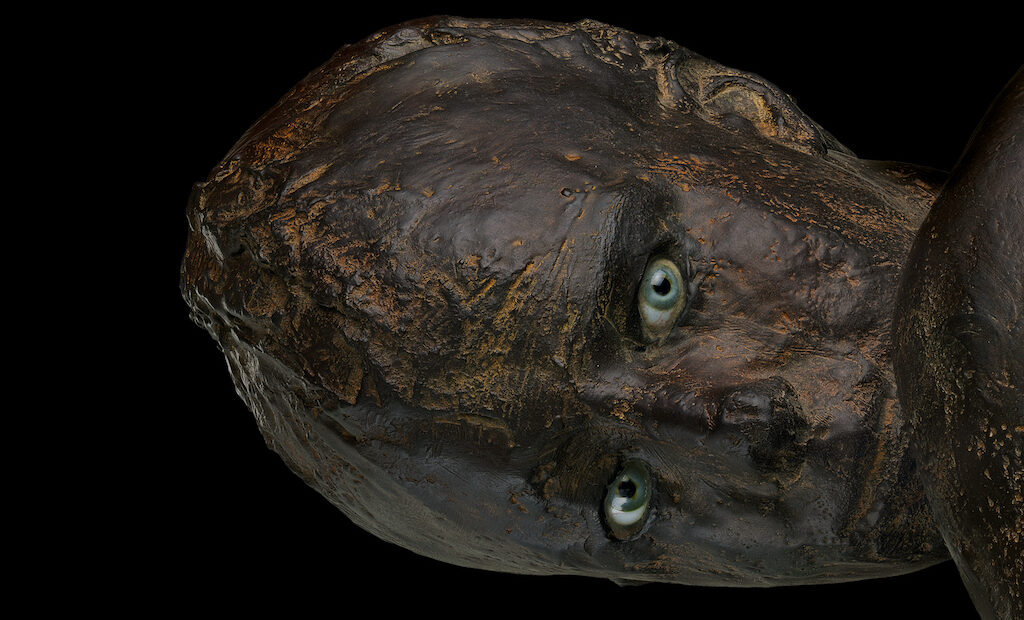

Kiki Smith’s 1994 Lilith bronze statue is crouching up a wall, defying gravity like a classic demonic woman in horror films. It was cast from a pose created by a ballerina. She defies the viewer and gravity, her nudity is enclosed, denying any voyeurism, and the blue glass eyes stare out of her tilted head. It is disturbing but effective. Lilith was Adam’s first wife, made from the same earth as him, but she transgressed by refusing to lie under him during lovemaking (the horror!) and, like a biblical Karen, Adam complained to management and got himself a new woman, while Lilith was released to do as she pleased (you could say that had been her plan all along).

Of course, it would not be an exhibition of feminine power without some witches. Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses (John William Waterhouse, oil on canvas, 1891) occupies a central position in the show. The semi-divine sorceress from Homer’s Odyssey was seductive and dangerous, endowed with vast knowledge of potions and herbs. This beautiful image shows Circe offering a poison chalice to Ulysses, who lurks nervously in the background, two of his crew already having been turned into pigs by the potion and languishing, looking as shame-faced as pigs can, at Circe’s feet. The piece is alive with detail: a censer smokes in the corner, every tile in the mosaic floor is depicted, Circe herself is rapturous in diaphanous gauze. It is fascinating to see a copy of the Malleus Maleficarum (the witch hunter’s manual) displayed on a page where some wag has graffitied in a penis. Naturally a penis or two had to slip in somewhere. A woodcut of witches cavorting with flaccid sausages, deflated breasts swinging, shows that witch hunting always said more about the witch hunters’ fears of sexual inadequacy and women whose fertility had left them (giving them more time for mischief) than it ever did about the persecuted women themselves.

Females were thought more susceptible to the Devil’s wiles in those days, due to the story of the “fall of man”. This is depicted in a woodcut print by Lucas Cranach the Elder, circa 1515. The serpent appears as Eve’s double, with her face and breasts plus a serpent tail, whispering in her ear as she proffers the forbidden fruit to a limp and ineffectual Adam. What is striking, amidst so many powerful myths, is how, well, lame Adam is. Do we really want to accept this as the blueprint for man? It feels like an invasion, an insult after the fantastic array. Of all the rich, diverse and strange myths, why choose to believe in one that casts such blame and contempt on women?

There is one minor quibble: the looped recordings of esteemed women giving their opinions on the show is distracting, especially when contemplating the sharp, cool majesty of Sekhmet. This is an impactful and prescient show, timely, as women’s bodily autonomy and socio-economic power is debated and denied in many countries. The impressions one takes away from the exhibition unique, but is essential viewing for all women: it leaves one feeling powerful.

Jessica Wall

Feminine Power: The Divine to the Demonic is at the British Museum from 19th May until 22nd September 2022. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS