“I wanted to sabotage it”: An interview with Mark Jenkin on Enys Men

Following the critical acclaim of his debut feature Bait, experimental filmmaker Mark Jenkin takes his latest project Enys Men (pronounced “main”) to Cannes Film Festival. Set on an isolated Cornish island – the title coming from the Cornish for “Stone Island” – the film sees Mary Woodvine star as an unnamed woman whose job is to monitor the island’s plant life. She lives alone on the isolated rock, and memories, ghosts and nightmares begin to haunt the her as the island’s past is unearthed.

The Upcoming had the privilege of chatting to writer and director Jenkin about his latest work. He spoke about his filmmaking process, the importance of Cornish heritage and breaking rhythms.

With your film containing themes of isolation, were you inspired in any way by the recent quarantine and lockdowns?

No, it wasn’t. It was all conceptualised before the pandemic. It did influence everything we were doing during the shoot.

We finished the theatrical run of Bait at the end the of 2019. In 2020 we had the BAFTAs, which kicked off another short theatrical run. That took us up to when the pandemic hit, and at that point we were getting ready to shoot Enys Men around May or June. Then we got pulled for a year. And when we came back to production, I think that’s the point that everything did inform what we were doing. We had to do some rewrites because of the restrictions. I’ve never told Mary what her character’s backstory was, but maybe that’s why she’s on the island She could be the last person alive. Maybe everybody else is a ghost.

How did you go about developing the physical film yourself?

This one I didn’t develop by myself’ this was developed by a lab. I’m endlessly fascinated by the physical film. I finished the shoot with a box of undeveloped film with these latent images. They’re there, but you can’t see them. They don’t really exist yet. I find that mindblowing. It’s alchemy.

I had a roll of Super 8 that someone gave me that was 30 years old, and they had no idea what was on it. I was just messing around in my studio one day when I decided to develop it. I processed it to a positive rather than a negative, and as soon as it was dry I put it on the projector, and it was this little girl running towards the camera on a beach. That girl has been stuck in that film cartridge waiting to run for 30 years. It was wanky, but even as a 46-year-old I still get excited about images on film and the first time I sent away my first Super 8 to get processed.

Is that part of the reason you decided to present Enys Men as an old and scratchy piece of film?

That’s just the by-product of the way that I shoot. When I did Bait somebody asked me how long it took me to get the film looking the way it did. That was my best attempt at getting the perfect image. I shoot on a 1970s clockwork camera; I shoot with very old lenses; I hand-process in a little hand-wound development tank, so with all those variables, this is the best that I could get.

With Enys Men it’s slightly different because I didn’t process it myself, so I did consciously affect the negative during the shooting, since I knew it was going to be processed by a lab, and I was worried that they’d clean it up too much and try and give me something perfect. On the log sheets I would say, “No digital clean-up. Don’t leave anything out. Even if it looks fucked, I want to do something with it.”

As an added thing, I underexposed the negative by two stops. Ordinarily if you did that, the lab would push-process it by two stops. But I didn’t tell the lab that I’d done that so it would all come back underexposed. And when I did all the colouring, the colours started to fall to pieces. I wanted to sabotage it a little bit.

There are a lot of reds and blues in your film. Is there anything that specifically draw you to use those colours?

When I first decided that I was going to to use colour, I decided that if I was going to use colour, I was going to use a lot of colour – let’s go really colourful because I don’t see the point in using muted tones. We didn’t tone it back. And once you have one primary colour that’s really jumping, all the others start. The blue becomes very blue.

There were times where I was having real trouble with the colour during post-production. I’d say to Denzil [Monk], our producer, “We could put it black and white.” And he just said, “No. We’re doing it in colour.”

The island feels like it’s coming alive with history. Did you have any inspirations in mind when you were creating this world?

I think that the time setting, 1973, was important in that it takes away mass communication. The isolation here is true isolation. It’s also a nod to those innovative genre films of the 1970s, especially those British almost-horror films.

I also really wanted it to be Cornish and not English. I wanted to move away from the English folk horror that’s about “Merry Old England”. There’s pastoral England, which is all about villages and Morris dancers, and then there’s the dark pagan thing that gets unearthed below. Cornwall is already the dark pagan thing, so we have to go even deeper into the living rock to find out where the disturbance is. This is very important: historically, culturally and even contemporarily, Cornwall is very distinct from England. We have an “ish”. Cornwall is the only English county with an “ish”. We’re the Celtic underbelly, the more primal bit.

I really wanted this film to be distinctly Cornish. There are the hard rock miners, the bow maidens – the women who worked above the mines – and the Cornish language as well. It’s not a rejection of anything, but an embrace of Cornish heritage.

How did you conceptualise the space of the island?

A lot of it was about rhythm and then subverting it. You undermine it and start playing with it. On a technical level, a lot of the rhythm is visual, but a lot of it is audio. That’s why I like to have total control of the audio. I don’t record any location sound – I do it all in the studio as I’m doing the edit. I build the sounds as I’m doing the rough cut, and the rhythmic sound then determines the visual edit. I always do that, but much more in this film because there was no dialogue to work with. It was all footsteps, doors opening, the stone dropping, the clanking of the mines.

In some ways it’s much more complex and much more time consuming to do that, but it’s something that I can do on my own away from the shoot – and it’s cheap. It’s a sort of one-man-band in the studio. I’ve got a bit of floor that’s up on legs that I can do all the footsteps with. A lot of it gets replaced later when we do the mix, but I need something to work with. I can shoot silently, but I can’t do a silent edit. If the rhythm doesn’t work then nothing works.

Andrew Murray

Photo: Quinzaine des Réalisateurs / Guillaume Lutz

Enys Men does not have a UK release date yet.

Read our review of Enys Men here.

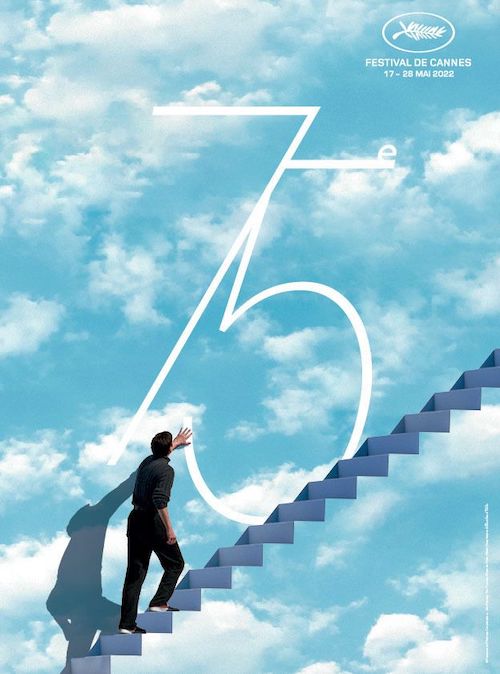

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS