“It’s never as I planned it to be, but that’s the point. I like that”: An interview with Marie Kreutzer, director of Corsage

After a German television series released shortly before Christmas – a time ripe with reruns of the 1950s movie trilogy starring Romy Schneider – and the Netflix Original production The Empress, Corsage is the latest project to tackle the myth-enshrouded life of Empress Elisabeth of Austria.

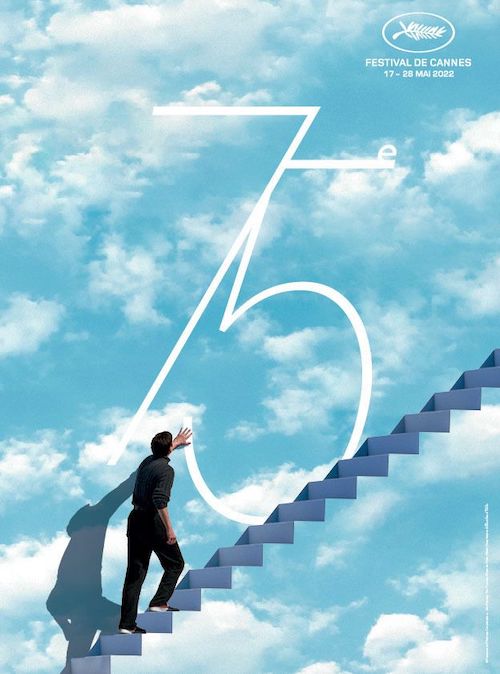

Marie Kreutzer’s unconventional biopic screened in the Un Certain Regard section of the 2022 Cannes Film Festival and won its lead, Vicky Krieps, the Best Performance Prize.

On the harbour-facing terrace of the Palais we spoke to the Austrian filmmaker about her relationship with “Sissi”, Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette and why the film’s crew was declared insane by the lab technician developing the film.

Did you also grow up on the Sissi films with Romy Schneider, like so many Austrians? How did your relationship with Empress Elisabeth evolve – she has a very different persona in your film?

I actually didn’t grow up with that, because I wasn’t allowed to see so much TV. I saw the films much later. But of course, I knew about them and I knew about the cliché, because whenever you pass a souvenir shop in Austria, you see Mozart and you see Sissi, and so we all know her.

But I didn’t deliberately try to go against anything; it’s just that the woman you see in this film has more to do with the woman I read about, when reading about her. I was actually surprised, then, because I thought even the young Elisabeth had nothing to do with the funny Romy Schneider version for me, from what I read. That was Ernst Marischka’s interpretation of that character – as all interpretations are possible, because it’s there’s only so much… There are some paintings and a few photographs, but the rest is all written stuff and there are many blank pages. You can make up your own Elizabeth on the way.

So what was your main reason to make Corsage?

The idea came from Vicky Krieps, herself, who asked me a few years ago if we wanted to make a film about Sissi. We did another film together, and she asked me after and I only laughed. I thought it was a joke, because, as I said, it’s just a souvenir shop cliché in Austria. But it stuck with me and at some point I started to read about her and I said to myself, “Let’s see if there is something in the material that interests me.”

Because whatever it’s going to be, it’s going to be big, because it’s a period film. I will not do it for the Sissi thing. No, I will only do it if it’s a good story. And I found it so interesting that she’s such a complex character – which, of course we all are – but when you see most princess movies, these are not complex characters, they’re just beautiful, suffering women.

So reading about her, I found it interesting that she found little ways of rebellion, that she was trying to create her own life within the very small and tight borders of her imperial life; that she was reflecting so much, she wrote poetry. She had a very sharp way of analysing things around her. She was in many ways ahead of her time and thought about the end of monarchy at a point where nobody would have talked about that. I thought she was very smart. She felt also quite selfish to me, when I read all this, and all of that interested me.

So I wanted to make a film about a woman, who was very isolated in many ways. And then the corset plays such a big part: the shaping and the whole work she did on her body play such a big part in all the biographies that you have. That’s also something that intrigued me because it’s not usual for that time. I was trying to find out for myself what could be the reason? I thought that, as someone who has no control over anything, because people always tell you what to do, the only thing you can control is your body.

And I found that also interesting in terms of the image you have of yourself and the image others have, especially as someone in the public eye, how big that image can get and how little it belongs to you anymore. You have to fulfil that all the time. That also has to do with celebrity culture, with social media, with how we, as women, always try to fulfil certain images in order to please and be loved for that. So I thought that there’s a lot in the material, which is actually very universal, even modern.

It’s actually the third or fourth production in a short period of time that deals with Sissi. Were you ever worried that your version might get lost in the whole Empress revival that’s happening at the moment?

Not really because, in this job, you’re always in competition with so many other films all the time – you know, if you go there for funding, if you want to cast actors or actresses who are very known, they might be in other productions, you’re always competing, in a way. It’s always like, “I’m faster” – “No, I’m faster, I will get this done.”

So I have learned not to think so much about other people’s films or not to compare myself to anyone.

I found it very interesting, actually, because there’s no obvious reason for this trend. And then, when I heard it was two TV shows, I thought, “Well, that doesn’t really have anything to do with us, because we don’t take anything from them. And they don’t from us.” It’s maybe another audience, or maybe, if people are really interested, they will watch both. And that was a little bit also what I thought about the other feature film from Germany – I thought this could I mean people who care; they will see both films anyway. So it was just a matter of who would be the first and how would we do it? That was something the distributers talked about. But, for me, when I learned that there are these other productions, we were already very far in the financing process. Of course, if you’re at the very beginning and then you hear that there are three other productions, you can easily think… But then again, my father said something – I was, I don’t know, 18 years old – and I said,”I would like to study this or that, but so little people get a job in this field,” and he said, “Well, you have to be one of them.”

And that’s something that’s always with me still. It sounds stupid, because it’s so simple. But that’s just what I’m trying to do.

Why did you decide to focus your movie on the specific period in Sissi’s life when she is just about to lose some of her iconic status?

It was very interesting to me because it was the time I knew the least about before – because we all know how she became an empress, we know how she died, but we know very… I knew very little about the time in between. And then, of course, because I wanted Vicky to play her, so it was clear that it couldn’t be the 20-year-old or 60-year-old empress.

I mean, Vicky, to me, is a young woman, but then when you find out that 40 years old was old at that time, this all fell into place, you know? And, of course, it interests me because of the things I talked about before – the image and being valued, because you are fulfilling the image of a beautiful Empress. What does it mean if you’re not beautiful anymore, maybe? Or what if you decide to not fit into that image anymore? What does that make you?

It all came together. For me it was clear. And I never wanted to make the kind of biography where you see something over many, many years – I think it never really works in films. It works in books, but in films it’s always cheesy, in a way, because you cannot work with the same actors. I always find it very difficult. It’s like “and then and then and then”. I just wanted to focus on a certain period.

What made you decide to include the modern elements – especially the music, which is the most obvious?

The music was already in the script. During the financing process I was asked several times, “Do you really want to use modern music? You mean like Sofia Coppola in Marie Antoinette?”. And I was always like, “No!”. I mean, I don’t like that film; I don’t want people to think of that film.

Actually, the songs were in the script because that was the music I was listening to while writing. I listen to a lot of music while I’m writing and I didn’t want it to be a classical historical film score. I always use songs and I wanted to use songs, and then I just had to fight for myself – I had to find a way to sell it. I mean, they wouldn’t say, “We will not give you the funding if you use modern music,” but they were all a little bit confused. And then I found out that I could maybe use it in another way and integrate it more, to blend it in by using other interpretations, using other instruments. Having it played live in the film, this was something we would also try, and with set design and costumes, those elements, which are actually modern or not as old as the story… You could always wonder, “Could that have existed?”.

So, ideally, what would happen would be that people hear the Kris Kristofferson song and say, “Oh, I didn’t know it was such an old song.” That was how we were thinking: to make it confusing, but not so in-your-face like, for example, Sofia Coppola did, which I personally didn’t like, because I could sense what she wanted… When I see a film, I want to be surprised. I don’t want to see the concept. But of course, that’s difficult because I’m a filmmaker, so I very often see the concept.

While we were watching the film, we weren’t thinking about Marie Antoinette – it reminded us more of Spencer.

Really? It’s the same production company actually.

And it isn’t immediately obvious to compare Empress Elisabeth and Princess Diana, but really they’re similar characters with a lot of the same struggles.

Yeah, actually, there’s a lot of similarities. I think it’s also why they are both such big myths – because they are great for projection. You know, we don’t know it all, and that’s very interesting. We just know they had a hard time and they were isolated both. But I saw Spencer only recently; it was produced almost parallel, so I didn’t know anything about the film until like two or three weeks ago.

As you’ve said, often in the film you ask yourself, “Could that have happened at the time?”– for instance the pierced ear of the photographer. But then there’s a scene with a mop and bucket that are very clearly plastic, and you become aware that these are deliberate anachronisms.

Yes, but that was actually the only thing that was not carefully chosen. We were going through the scene, because it was a Steadicam shot, and you always have to go through it several times, not with the actors, but with someone walking. And then the art department people were still cleaning. So it was standing there and somebody wanted to remove it and I said, “No, no, I love it.”

At that point, everybody on-set already knew what we were doing there. It was very funny actually – we shot on film and the film was developed in Belgium, and there was a guy in this development facility, in the laboratory, who always wrote us with some kind of validation that everything was good with the material. And he had to see it everyday, the dailies, and he always wrote us an email saying “Everything is good, but there’s something in the background that shouldn’t be there.” And he really didn’t stop. He didn’t realise that we wanted that. It was like a joke on set: “What did he write?” .

At that point I think he thought we were crazy.

The buildings you used in this film also stand out, because some of them are not renovated at all, while others are in impeccable condition.

I mean, I never wanted it to be the beautiful, classical period film. I also found it interesting that, at this time, the monarchy wouldn’t be lasting much longer, that it was already the end of an era. And people didn’t want to… they tried to not see it. And I wanted it to be seen in a way. I always said to the set decorators, when I went in on-set to confirm that it was good, “Take that away, take this away.” So they moved out half of the furniture again. I said, “I want it to look as if the expensive furniture has already been sold.”

So there was three times as much furniture on-set, originally. I wanted the emptiness also to show her isolation, and to show the end of an era – that was also why we chose the old castles, the castles which were not renovated, which had that patina a lot.

And we were always extremely happy if we found that, because we shot a part in Luxembourg and Luxembourg is a very rich country. All the castles there are perfectly renovated and it was not always easy to find these places, and we were on websites like Hidden Places – you know, these dead, old castles or villas, which stand in the middle of nowhere. And then I found photos and I said, “You have to find that place.”

It was really crazy, finding all of these places took a long time.

You mentioned that Vicky brought up this project. Was she also involved in the writing process?

No, I don’t collaborate with anyone when writing. I cannot. It’s just me and my thoughts, because as soon as you begin to talk about a script, you want to make it work. And I don’t like that because the things you come up with, when you try to make it work, are always classic. They are, because you have seen them so many times, because you’re reproducing what has already worked. So I always think it’s better for me not to explain what I’m writing while I am doing it.

And whenever you work with someone else you have to. When you’re shooting a film, you have to explain yourself all the time.

But at this point, when I am writing, I’m just making it all up and I have to be on my own. And it wasn’t even an option. I mean, she was shooting all over the place and we didn’t see each other for two years. She didn’t even know I was writing. I sent it to her when it was almost finished.

How much of the narrative is real and how much was fiction?

I couldn’t tell you in percent, but I had one book that was very interesting – it was from the 1960s and it was a biography that was a little bit like this: “And then and then and then”. There was one chapter for each year of her life, and it was really like, “In January, she went here, and then she travelled there”.

It was also interesting for me to see how long it took her to go from here to there. Because it was 1878, she couldn’t take an airplane. So I really had like a schedule of her year 1878 and there were a lot of interesting things. For example, the whole story with the riding teacher and her sister is true – they had a conflict about her being too close to him. After that, she really said – her son wrote it down and so many people confirmed it – Sissi said, “I don’t want to see her again.”

And they actually never met again. Because she was so angry that her sister was speaking behind her back and tried to make her look bad. So that, for example, is just history.

But then there’s other parts, which are made-up – the ending, of course. I find it interesting to move within facts, but then take what I needed and just forget the other stuff.

It’s not easy to say, because yesterday I got the question like, ”Just one quick question,” after the interview, “Can you tell me exactly what was made up and what wasn’t?”. But that is a longer conversation. Sometimes I don’t even remember exactly.

Speaking of the riding teacher, there’s this flirtation, and it’s very interesting that she says something along the lines of, “I love to look at the way I’m being looked at by you.” This being “looked at” and scrutinised is the root of her unhappiness, but at the same time in this situation, it’s what she craves.

For me, she’s at the point where this begins to change, where she realises that she feels only love because she fulfils that image – and that is the love she can still always get. But that is not love, really. And I think what I meant with this scene is that she wants to be close to people, but doesn’t really know how to do that because she didn’t have friends like we have, and her sisters were not of the same status as her: all her sisters were married to other aristocrats, who were not as high-up as her husband. People were either above her or below her, there was no one on her level. And I wanted to show that she needed to be close that she longed to be close to somebody – that’s why she always lays down in everybody’s bed – but that she doesn’t really know how to get real intimacy, to come close to someone and really be seen and be held. The only thing she knows is that she can get that confirmation that she’s beautiful, again and again. But, for me, it’s about her finding out that that’s not it. I mean, that’s not love; that’s not really what fulfils her.

We loved the costumes in your movie. What was the process like of collaborating with the costume designer?

Oh the poor costume designer… No, no, we’re good friends. But it was really a hard time for her, as well, because I wanted it to look much more simple, more simple and more… Whenever I sort of got a say, it was, “No, take that away, take that away.”

So in the end, the dresses were really very simple – much simpler than they actually were at that time. And, if you know fashion, you know that making it simple is the most difficult thing – the most expensive thing, actually, because it has to be a really good fabric. There were a lot of women sewing all the time; it was all handmade – I mean for the actors, not for all the extras – but for the actors everything was handmade.

How difficult is it, after all the research, to then let go of the information and to let your imagination run wild?

I mean that’s just screenwriting: you have to reduce it. I always try to throw everything out – what I don’t need. I have learned that through my films; I don’t really know how to explain that, it’s just something that you know, at some point. Also, in the editing, it is very important to let go of things, even when you have shot them beautifully. Sometimes it’s scenes that don’t work in the film that are beautiful by themselves, but they don’t fulfil in the film what they fulfil in the script. And that’s also why I love this job – because every part of the process is so different and the film develops all the time. You never know.

When people ask me, “Is it as you wanted it to be or as you planned it to be?” I always say, “It’s never as I planned it to be, but that’s the point. I like that.”

Selina Sondermann

Corsage does not have a UK release date yet.

Read our review of Corsage here.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Watch a clip from Corsage here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS