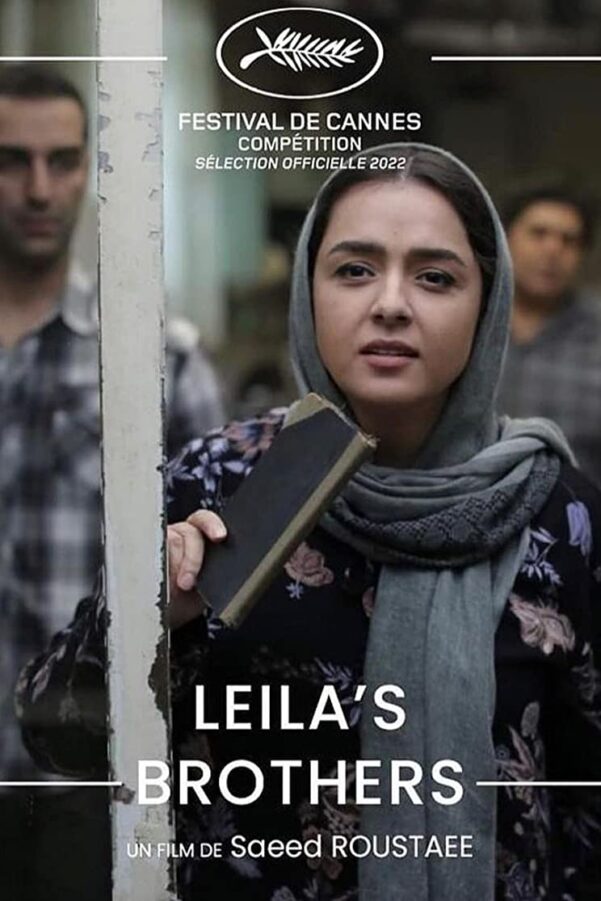

“How to make a genuine portrait of life”: An interview with the stars of Leila’s Brothers

Iranian filmmaker Saeed Roustayi’s third feature was invited into the Official Competition of the 75th edition of the Cannes film festival this year, where it won the FIPRESCI Critics’ Prize.

What set Leila’s Brothers distinctly apart from its co-competitors for the Palme d’Or was the stellar ensemble cast that breathed life into the complex family dynamic at the centre of the film’s plot.

We had the opportunity to speak to three of the protagonists: Taraneh Alidoosti, who stars as the titular Leila, Navid Mohammadzadeh, who plays the cerebral brother Alireza, and Payman Maadi, portraying his impulsive counterpart, Manoucher. In a brief chat on a picturesque beach boardwalk, the stars shared their thoughts on creating authentic performances and difficulties for actors in Iran.

We just spoke to your director and he said you rehearsed for several months. During that time, did you have any input on your characters?

Navid Mohammadzadeh: We talked about the film for two, three years before shooting. So we knew what we were going to do – everything was there. Of course, when we work, we work the way the director wants us to; it is constructed. When we are shooting the movie, it all comes alive and we are giving life to the characters. It’s not like a robot – we become those characters, we are not ourselves. He directs us, but we become Alireza, Leila and Manoucher.

Payman Maadi: I did three films with Navid, with Saeed Roustayi and, you know, all these characters were different. Coming up to these characters is different – one character differs from another one. As Navid said, we talked about this film a long time before shooting. One year before, even, I was thinking about this character, about Manoucher, and I talked a lot with Saeed, who is a great friend of mine. The thing is that, with these conversations, the role changed. So, especially for my character, we had this revised version in the screenplay after our conversations and sharing thoughts together.

There is a small but interesting shift in semantics between the French and the international title (Leila and her Brothers vs Leila’s Brothers). Do you think Leila’s family was misogynistic towards her?

Taraneh Alidoosti: Whether we believe this or not, Leila definitely thinks that way. She states it perfectly: fighting with her mother, she says, “You are the person, who loves all of your sons more than your only daughter. You hate every woman in the world.” That is actually Leila’s dialogue. And we see that, only because she is a girl, everything has been taken from her – her opportunities, her courtship, everything. The emotional stuff that’s happened to her… she is younger than many of them, but still manages to be a mother figure to them.

I think if she was one of the brothers, everything would have been different; everything would have been easier for her. In that case, if Leila was a boy, he would be a hero. But only because she is the girl, she has to fight by herself to convince those four men, that she loves so very dearly – she needs to convince them of what is good for them.

What do you consider the advantages and disadvantages of being an actor in Iran?

PM: There’s a general answer to this question: for any actor in the world there are some advantages for sure, and there are so many disadvantages. We all know that fame is always good. You have so many possibilities, being famous and being in art, creating… You’re living somebody else’s life, which is everyone’s dream – you want to be someone else and you can play.

There are some bad things, like you cannot do many things that normal people do. This is a general thing – American, French, doesn’t matter.

Being an Iranian actor, there are some issues that no other actors in the world would understand: we have to consider so many other things; we have to be creative in so many senses; we have to think about how to imply this and that. There are many difficulties to overcome, especially for women. For example, I’m working in United States, too. I’ve worked in many other countries, but they cannot do that, because they cannot play without hijab. This is our advantage – I’m not proud of this; you know it’s not fair for the women. This is just one particular issue. There are so many other issues.

NM: We have many issues: the relationship between men and women in the films – we cannot touch each other. The woman has to wear hijab, and when we are here, we have to be very careful, walking together, walking with another woman – with your wife, even, it’s difficult to have a normal relationship here.

We live in a region, politically, geographically, with many issues and that could be great because we are dealing with these issues and then we can just act. But… Budgets for actors or actresses in the world: okay you can have a big house everywhere and nobody talks about that. But in Iran when you work and even if you earn money, maybe you cannot buy a house, you know? But everybody will just assume and say that we have money, that actors have money like in other countries.

Then the thing is, for example, here, you have a film from Out of Competition but it’s a Hollywood film, and every media will be on that. We are from Iran and we are in the Competition but we don’t have that kind of attention – even though you are doing the same work as other artists and other actors in the world. And we are doing a lot, but we don’t have the attention because it is like in the world they want to have the attention in some regions and not others.

We were in Venice, we were in Berlin, we had Oscars, but do we have the same publicity from the media that a Korean movie, for example, will get?

I have eight or nine international prizes, but that’s the first time that I can come to the Cannes festival in the Competition. Art should be universal, and doesn’t have to have borders. But, as you can see, regions have borders, and so art has borders.

In a press conference, when you have an Iranian film, you talk about the socio-political, about the economical, but not about the movie. Look, I have to talk about kissing my wife on the red carpet in the press conference. That’s because we are coming from that region, so we have to talk about that in a press conference and not about the movie.

I told you those things but, by the way, we will stay in Iran and we want to work in that cinema, in those theatres. We want to be in that country because it’s for our people; because when they see our movies or our theatre plays, they can see that we are not taking orders…

TA: We don’t have the same narrative as the system wants – so that’s the only hope that people have, probably. They can be represented in their culture, through movies and art, through artistic values.

NM: It’s a cultural war and we are the targets. It is really coming from a system that wants the people to be in front of us and not beside us. We are from the people and working for the people, but when you are going on social media, that system tries to pit you in a war [against] our people, and that’s not what we want.

Wherever we are, we are actually very happy, of course. But all the time we are anxious: what to say and what to do? Which word do we have to use?

The traditional Iranian cinema, the one of Kiarostami, is very close to Italian neorealism in the way it worked with non-professional actors. How do you feel about the situation of Iranian cinema today, working as professional actors?

PM: That genre and that style of cinema is my own ideal performance, and I can tell you I follow the steps of those non-professional actors myself. Part of my homework, when I research to reach the point that I desire as an actor, is watching documentaries, watching movies like that. So that is not a used-to-be cinema and we are not the future of that cinema. That cinema still exists.

Mr Kiarostami himself always said that his ideal for casting is professional actors, who can act like the non-actors – “since I cannot find any of those I always bring in the non-actors to do the performances”.

That’s what we’re trying to do. It’s all about reality and, you know, it’s about authenticity. It must be pure, genuine. If we can do something like that, and you believe it, we’re doing the right thing.

It’s not us or Kiarostami. All around the world, acting is changing. Nobody today acts like Humphrey Bogart anymore. We always worshipped him, and we always worshipped Katherine Hepburn and all of those classic actors, but today’s acting changed.

I think our ideal is to copy people. I copy you, the way that you’re sitting and the way that you are listening. We don’t copy Bogart, we copy normal people. We have to find the right person and get close to those guys. We owe this to Mr Kierostami and Mr [Asghar] Farhadi, and so many of these great filmmakers. This is what they dedicated to the cinema: how to make not only good films but how to make a genuine portrait of life.

Selina Sondermann

Leila’s Brothers does not have a UK release date yet.

Read our review of Leila’s Brothers here.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS