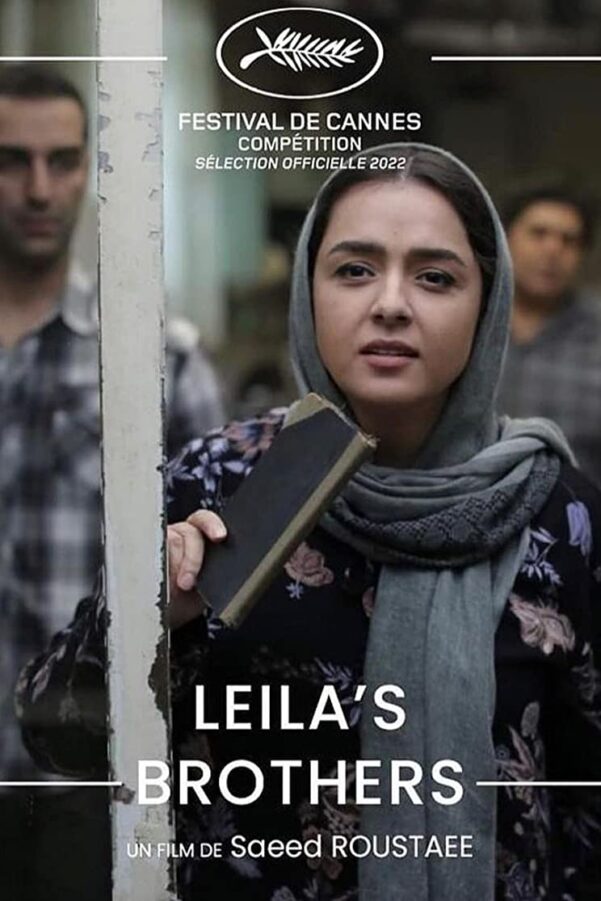

Leila’s Brothers: An interview with Saeed Roustayi

After his second feature, Just 6.5, was part of Venice’s Orrizonti section in 2019, and nominated alongside Drive My Car and The Father for Best Foreign Film at the 47th César Awards, Saeed Roustayi’s latest work is screened in the Official Competition at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival.

Iranian production Leila’s Brothers tackles the country’s political turmoil through a heartfelt family drama. The Upcoming spoke to the young filmmaker about his art and how it is informed by his life.

In your previous films, Blockage and Just 6.5, there is an urgency for the characters – a race against time; this is even the case in Leila’s Brothers to some extent, even though it is more of a family drama than a thriller. Do you still consider thriller a genre that influences all of your work?

I’m not really sure all my films are – maybe 6.5 is a different issue – but in general, I wouldn’t say that my films are really thrillers. Even if there is suspense, it’s resolved quite quickly, I mean, you quickly get to the point of the resolution of the suspense.

I think what I’m really interested in is this issue of human relationships, of a family relationship but also all the intricate relationships between human beings. That’s the kind of cinema I’m interested in, and the kind of cinema I make, so I’m not sure that suspense is so relevant.

As for 6.5, maybe this thriller aspect or the suspense was, for me, the best way to focus on the absent figure. Because one character is missing – he’s absent – it’s a much more handy and convenient way for the viewer. As filmmaker, it makes your life easier also to depict and to develop something about this missing character and then you can focus on other aspects.

In Leila’s Brothers, footage of Donald Trump on television in the background of a scene is almost part of the characters’ daily lives. Why was it important for you to include this in the film?

Something very striking in Iran is the very straight and direct relationship between people’s lives and international politicians – it’s an obvious link. These international figures really are present in our everyday life, in everyday conversation, because sanctions are everywhere. Yes, the daily inflation that has immediate impact on people’s lives is linked to the decisions and to the behaviours and to the statements of these international figures.

Of course, there are also wrongdoings from the local government, but the sanctions started with Ahmadineschād, then there was a second set of problems with Trump, and so this is something that is on everybody’s mind. It is part of everybody’s life and conversation. People talk about it every day, as if it was part of their lives. So, it was, for me, interesting to also include it as something ordinary and that has to do with people’s lives, and to show the harm that is done by the sanctions and by these general international crises. The first target of the harm are the people. No one other than the people are suffering and are undergoing the consequences of the sanctions.

Does the ceremony you depicted, of giving gold, of giving the biggest wedding present to become a family patriarch, really exist in modern, urban Iran?

Yes, it does exist but I don’t know how to justify it. That’s what my film does.

There is also an immense contrast between the social condition of the family and the big, extravagant wedding celebration.

Yeah, but that is possible because the wedding is for show. Everything is fake; they’re just pretending, it’s not real.

To some of us who weren’t as familiar with the country, Iran itself felt like another protagonist in this film, it is so inextricably tied to this family.

You’re watching the story of one family but it gives you an insight of Iranian society in general. If this is what you experienced, I’m really happy.

The reason why I show Alireza in this factory in the opening scene is that there are so many people to show, that there are that many of them. I choose to follow one of them, but I’m sure that all the others are not in a better situation than him.

Leila is such a strong, active and progressive woman. Why is she stuck in this family? Why doesn’t she just move away and move on with her own life?

Because the thing is that she wants to have a family; she doesn’t want to leave them behind. And, I think, as it is said about this man, who actually divorced and who offered to see her, she said “no”, because she wants to help her family and she wants to pull her family together and do something for all of them, not to be the one who just leaves them behind and moves on with her own life.

And the thing is what I described in my first film, you can think that it’s people’s own decision or their wrongdoings that cause their problems. But, here, it’s obvious that it’s coming from the outside, even though no matter what decisions people take, they have reality impacting their lives. They couldn’t get out of their control and now, in Iran, prices are tripling overnight, so there’s not much you can do. I mean, no matter what decision you take, you’re just swallowed by the situation.

In the press notes it says that Greek tragedies and Shakespeare were some of of your inspirations. Are there other influences – perhaps other Iranian filmmakers – who inspired you, not only for Leila’s Brothers but throughout your career?

Well, I learned filmmaking from life and I learned living from films – that’s really how it’s been for me all the way through. My films are made from the material that life gives me. My dialogues, you can hear it from people; situations that I describe, you can witness them in people’s life around me. That’s really what feeds my cinema.

At the same time, when I feel down, I watch a film. When I feel hopeful, I watch a film. It’s in films that I learned how to lose faith, it’s in films that I learn how to gain faith again, how to go on with my life, how to try and improve my environment. There is this very strong and reciprocal relationship for me between cinema and life, and that’s that’s how I make my films. I make them with the material life brings me.

In a story with this many protagonists, was it difficult to retain their individual voices?

Well, I really tried very hard to make them all unique in their own ways and extremely specific in the way they are, in the characteristics that they have, the lines that they say. What is said by Manouchehr cannot be said by Alireza, or the way Leila reacts cannot be done by Farhad. I mean, they’re there, you cannot interchange them, they’re all very unique and specific. This is one of the very primary rules of scriptwriting that I tried to respect – and I hope I managed.

After bombs and sanctions, your film shows that social media has also become part of warfare.

It’s very obvious what I say, in the scene, that the gold coin value was six million, and then there was a speech and it went to seven, and after a tweet, it went to eight.

The character is asked, “What’s the tweet? Is it a bomb?” and he says “No, even with a bomb, it shouldn’t happen.”

So it’s showing that, obviously, what’s going on is worse than war – that people who live at war are in a better situation than us.

There is a lot of shouting in Leila’s Brothers. Is this representative of society’s situation of not being heard?

I’m not much of a symbol person, I just want the scene that I am describing to be credible and authentic.

So there is shouting because there is tension. I wanted to shoot in a small location, I mean, the set that we had was hardly larger than 100 square metres, because I wanted us to be in the actual situation in which these people live in extreme proximity. They have no distance, they have no privacy, they have no opportunity to take distance with the other one. They’re always seeing each other in close shots, they never get to see a wider shot of the other. And this puts them in a situation of tension and of difficulty. So they shout to try and make the other understand what their point is. They don’t always get understood, but that’s at least expressing this tension.

The performances you elicited from your cast are excellent. What’s your directorial approach with your actors?

Well, my approach is that, first of all, I already have the actors in mind when I’m writing; I already know who I’m writing for. And I am always careful to actually work with the actors I have chosen beforehand. Once the script is ready, once they’ve read it, we have a long, long process of rehearsals. We had two full months of daily rehearsals, where we rehearsed individually, we had duets, we had collective scenes, we were really talking about each scene. We focused more on the difficult scenes. We really want the script to be perfectly known in practice. Once we start shooting, we are extremely faithful to the script.

Selina Sondermann

Leyla’s Brothers does not have a UK release date yet.

Read our review of Leila’s Brothers here.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS