Plan 75: An interview with director Chie Hayakawa

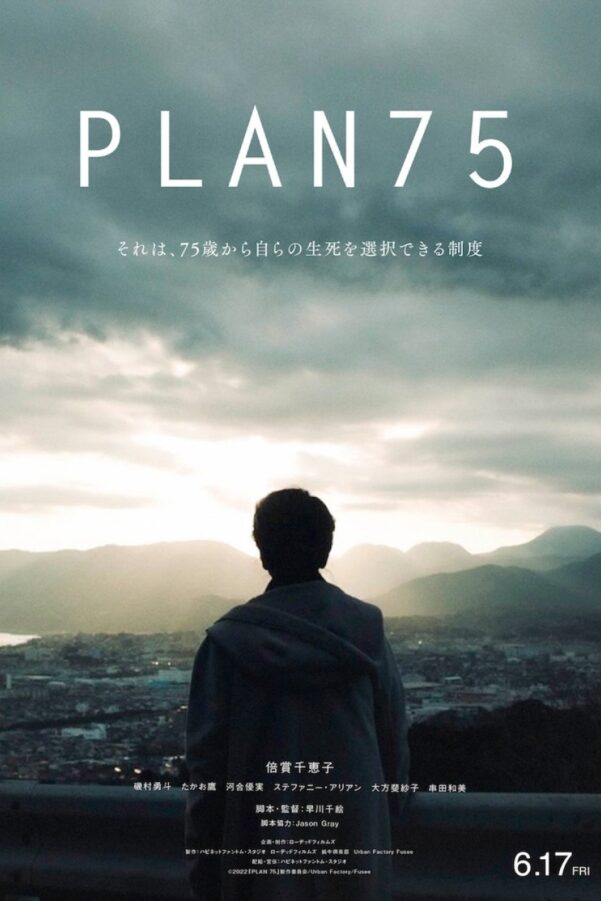

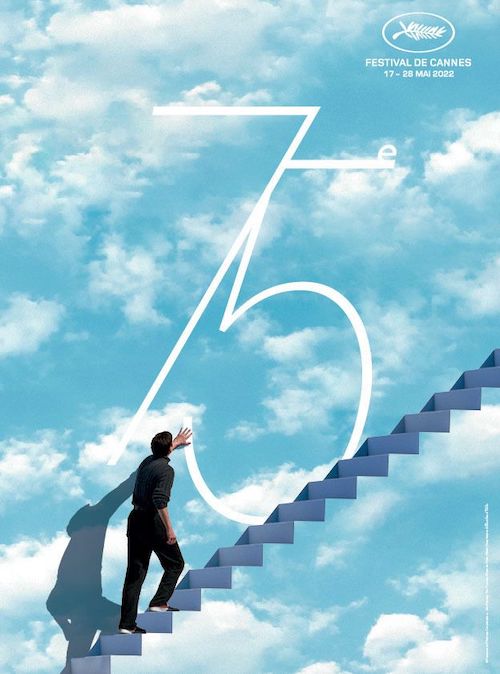

In 2018, Chie Hayakawa contributed a short film entitled Plan 75 to the anthology feature Ten Years Japan. Building on her vision for Japan’s future, the director’s feature film debut deals with a Japanese government that encourages its elderly citizens to commit suicide. Plan 75 premiered at Cannes’s Un Certain Regard section, where it received a Camera d’Or Special Mention. We spoke to the Japanese filmmaker about her concerns regarding the growing ageism in society, the part the pandemic played in the film’s development and her trust in her audience to feel the right thing.

Your film can be seen as a dystopian view of the future, but it is portrayed so very realistically. Do you think what you depict could really happen?

This can happen. I feel that way. It’s not going to be in like two or three years time, but in five to ten years, it not only could, it’s likely to happen, I feel. I want to prevent that. So I decided to make a fictional film to invoke the issue to people in Japan.

Where did the first sparks of this idea come from?

In the past few years, I feel that in Japan, society has been moving towards a very intolerant atmosphere. Society tries to get rid of the “weak”, the socially weak people. There’s been discriminative words, by politicians and well-known, famous people, against the disabled.

This is not right, this direction the Japanese society is going in. In 2016, a massacre happened in a disabled nursing home, where a former employee stabbed to death 19 residents of that facility and injured more than 40 people. That guy said he did it because the disabled are worthless and a burden to live in our society, that we don’t need them, that we should not spend money on them. And I fear he is not the only one who feels that way. I feel the same kind of atmosphere from society; I felt so scared. That anger and that anxiety for the Japanese society made me think to make this film.

To me, this film felt so relevant – also internationally – because it reminded me of the way the UK dealt with Covid and how many parts of Europe have grown to feel now, as well – that they no longer care to protect the most vulnerable.

Yes, I actually started thinking about this project long before Covid, but when Covid started, I was scared and surprised that this is really much closer to reality than fiction.

I was overwhelmed at what was happening, and asked myself if I should make this film now, because people are already suffering and are already anxious all over the world. Should I make the film to increase people’s anxiety?

I was really struggling… if I should make it or not. But then I started thinking that I should find some kind of hope to this film, I have to have a message in this film. So the Covid era affected this film, especially how to end the film.

Euthanasia is not currently legal in Japan. What’s your personal view on that?

My personal view is not that I’m against it; I don’t want to deny either side of the argument – I feel compassion to both of them.

Also this film is not about saying it’s either good or bad, euthanasia is not the point of this film. My criticism is towards the intolerance of society.

I wanted to depict the attitude, and I want to criticise a society that provides the choice of death to people who are suffering, instead of providing support.

It’s quite hard to survive and live comfortably for elderly people.

Living a long life used to be a good thing; it was considered to be a precious thing. But now, people feel like being too old is not really a good thing. People worry about being poor, worry about getting dementia, worry about losing their house. The ageing issue is really very serious shadow cast over the people.

What works so well is that you are not spoon-feeding the audience with what to think, but you make them feel something for themselves. It’s particularly impressive considering this is your first feature film.

Thank you. Yes, I trust the audience. Nowadays, especially in Japanese film, there’s so many explanations, it’s all so designed in that way. I don’t like that kind of film.

I want to have the audience as a partner in making this film. Like they are your co-writer or something, you’re working together with the audience. I trust the audience with their ability to feel. I want to leave it open to the interpretation of the audience.

What is the research for this film like?

I interviewed about 15 elderly people, women especially, and asked their life stories, they would feel about Plan 75, if it existed. Also I talked with Filipino caregivers, who are working in Japan, and the people working in care facilities and in the welfare system.

What surprised me especially is that the elderly women, most of them, I believe, they said they would want to have that option, that feeling of security, because they are so worried about the future. If they are alone, if they’re single, and have no child who can take care of them. If they don’t have money and they get dementia, if they get sick… there is a huge amount of anxiety affecting their life. Instead of living in fear, they would rather have that option of being able to die peacefully with no worry. That surprised me and I feel so much pity. If society had enough support for them, they wouldn’t feel that way. But the way it is now, the support of the government is insufficient, so it’s natural that they feel that way.

Without explicitly stating it, you are pointing a finger at what we are losing if we dismiss these people, all the stories they have to tell, the experience they have lived. You said you conducted your research with elderly people, but was there also special relationship with the older generation that predated this film?

My grandparents passed away before I was born, so I don’t really have a personal connection to the elderly. But when I thought about building up especially the character of the uncle of that young boy, I was inspired by one guy, whom I met in the screening of my short version of Plan 75. He said he is strongly against Plan 75 because he was in his 70s, and he said he’s really proud of himself – that he built the Japanese economy. He worked so hard after World War II and his generation was the one to rebuild and the Japanese economy flourished. But when they got older, he felt disrespected by society because of the ageing issue, he felt that people think of them as a problem. He felt disappointed and upset about this attitude.

So I realised that in certain age groups, like the people in their 70s, and 80s, they have pride that they have been devoting themselves to Japan. So that’s why that uncle in the film has a history of donating blood, because he tried to devote himself to people, also by building villages and dams and stuff. They have a strong devotion to the nation, and those people are about to be thrown away by their country. So that kind of sad irony is what I wanted to depict in the film.

To end on a more positive note, let’s quickly speak about the festival. You were here before with one of your short films, right?

Yes, in the Cinéfondation flourished – it was eight years ago? I’m so happy to be back here. And also because for this film, we did post-production in Paris with our French partners. So now it is nice to get all together here in Cannes. I’m very, very happy.

Selina Sondermann

Plan 75 does not have a UK release date yet.

Read our review of Plan 75 here.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Watch the trailer for Plan 75 here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS