“This man wants to die because he loves life – that’s the paradox”: François Ozon on Everything Went Fine

Everything Went Fine is the emotive new film from revered French director François Ozon tackling the taboo topic of euthanasia and assisted dying from the perspective of a daughter approached by her father to help him die after suffering a paralysing stroke. It’s adapted from the autobiographical story of the same name written by screenwriter Emmanuèle Bernheim, who was a good friend and collaborator of Ozon’s, but whose very personal story Ozon did not feel ready to take on until after her sudden death from cancer.

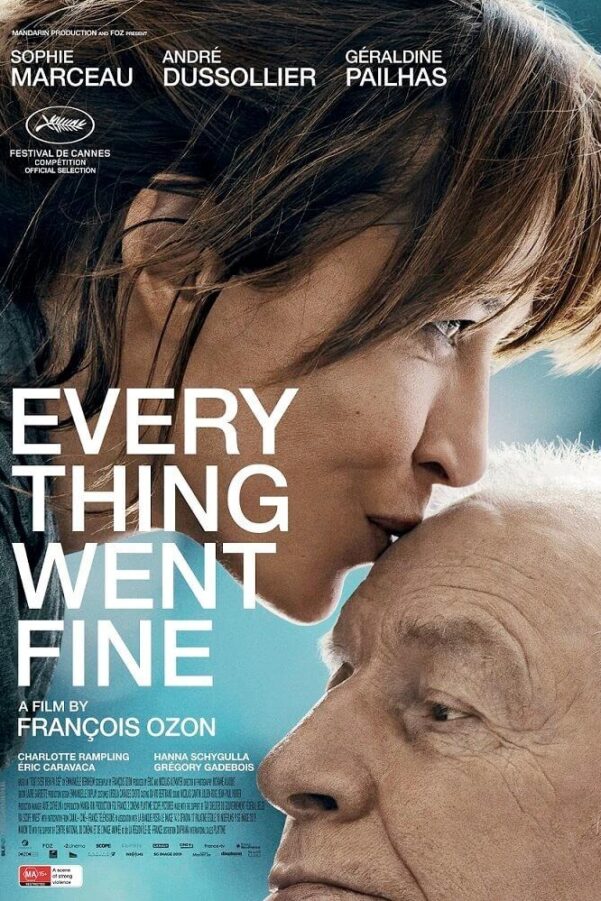

French superstar Sophie Marceau takes on the role of Emmanuèle to typically exceptional effect, while André Dussollier is her cynical and brutally unkind but nonetheless charismatic father. Her sister is played by Géraldine Pailhas and Swimming Pool-starring Charlotte Rampling returns in a small but crucial role as Emmanuèle’s estranged mother, who in fact did not appear in the book but was also an accomplished artist, herself suffering from her own ailments in the form of Parkinson’s and chronic depression.

Resisting sentimentality at every turn, Ozon elicits naturalistic performances from his astute cast to delve his audience into the messiness and sharp-tongued wrangling of family dynamics while also prompting them to ask themselves what they would do in their shoes.

The Upcoming had the privilege of sitting down with Ozon in London ahead of the film’s release in the UK to discuss his relationship with Bernheim, his approach to adapting such a personal story for the screen while making it his own and finally getting to work with Marceau. We also discussed how the right to euthanasia remains a contentious topic, both in society and from a legal perspective, yet the filmmaker wanted to focus on depicting with authenticity the very real and human relationships between these family members dealing with the same questions we may all once day face, and strike a tone that captured André’s love of life in spite of the heavy subject matter.

Hi François, so lovely to meet you. Could you start us off with a brief introduction to your latest film, Everything Went Fine. If you were describing it to someone who didn’t know anything about it, what would you say?

It’s a story of the difficult relationship between a father and his daughters. It’s an adaptation of a novel by Emmanuèle Bernheim. And it’s a true story she experienced with her father in the last moments of his life.

Even the backstory to the film is moving and fascinating in the sense that you met Bernheim and connected with her originally as a screenwriter, then it was only many years later that you read her book and only after her death that you decided to adapt it for the screen.

Yeah, it was a complex story! Emmanuèle Bernheim was a very good friend of mine I met when I worked on Under the Sand. I had some problems at the time with the script because everybody said it would be of no interest: “It’s a story about an old woman, nobody cares!”. We had a lot of refusals and rejections of the film. So I met Emmanuèle, who was a famous writer, and I asked her to help me. And we became friends. She helped me work on the character of this woman. And I loved to work with her. But it didn’t help, we didn’t get more money because she worked with me. But thankfully Charlotte Rampling made the film and it was a big hit in France. It was a big success. So it was a sweet revenge! And after that, we became good friends. We worked again together on Swimming Pool, Five Times Two and many other things. And some years ago, she published a book about her father. She sent it to me first, saying, “there are some other people who are interested in making a film, but I would like you to make it”. I read the book and I loved it, I was very, very touched. But at the same time, it was so personal, so intimate, it was so much her story, I didn’t find my place in that moment of my life with the book. So I said to her, “I’m sorry, I don’t feel able to deal with that”. And she said, “Okay, no problem”. And she began to work with other people. Very sadly, she had cancer, and she died very fast, it was such a shock for everybody. After her death, I read the book again. It was a way to find her again. And suddenly I had the feeling – I knew how to adapt it, I had the key. And I said, “maybe I can try to make an adaptation”. It was a way to work again with her in a certain way. And to understand better what she went through. It was a way to understand better her relationship with her father.

What was your process or approach to the adaptation? Obviously, she herself was a screenwriter, so that must have meant the book lent itself to being adapted. But when a story is so personal to someone else you must also need to balance that making it your own when you make it for the screen?

The book was very precise, full of details, and the way it’s written is close to a script, with lots of dialogue, very simple, very action-oriented. So it was quite easy to make an adaptation. But there were some holes or gaps in the story, things I didn’t really understand. And so I did some research, I spoke a lot with her husband, Serge Toubiana, with her sister, Pascale, and I asked her many questions about things I didn’t really understand, especially about the lover of the father. It was quite a big thing: in the book, he is called “GM”. So I asked the sister, “What does it mean? Everybody else has a name, why is he “GM”?. And the GM stands for, “Grosse Merde” like “big shit”. So that’s why it’s like that in the book! So I used these kind of things. It was like a secret language between the two sisters, a complicity. The sister told me about many other small stories which were not in the book. And I also realised the mother, Claude de Soria, didn’t exist in the book. For me, when I discovered that Emmanuèle’s mother was a sculptor, was an artist, it was quite a shock. And she’s a great artist! So I wanted to put her in the story and to develop the relationship with her daughter. So I put some of the things – all the Holocaust background, which was not in the book, but which was in her life – I decided to put all these elements in to enrich the film.

With a topic that you could say is quite taboo or people struggle to talk about frankly, the idea of choosing to end one’s own life with euthanasia, you could have taken a more political approach but instead, you zero in on this family, these individual characters and the personal relationships between them. So why did you decide to approach the subject matter like that, and in what sense do you feel human stories can be a way in for people to think about difficult topics?

I think I wanted to share her adventure, her emotions, her feelings, and I didn’t have an opinion [on euthanasia] when I started making the film. I didn’t know. You can’t know what you would do in this situation if you are not in it, if your father or your mother haven’t asked you what Emmanuèle’s father asked her. Today, you can’t say, “I would do that” or “I wouldn’t do that”. You don’t know. So you have to be in the situation yourself. But I had the feeling while making the film, that I would have an opinion by the end. And actually, I do have an opinion now. Because, I realised it was so hard for the daughters to have the responsibility of organising the death of their father on their shoulders. So I think we need laws, very strict laws, which allow people to have a decent end of life, and allow people to be free.

Also, what’s very interesting is this man, the father that’s at the centre of the story, he’s not necessarily likeable.

No, absolutely not! He’s a monster.

He’s a bad father, he says she was ugly when she was younger. But there’s also so much love there. And they make each other laugh. So what did you find interesting about exploring that character and capturing his charisma in spite of his flaws?

I liked that the story was not sentimental. Perhaps because that generation of parents didn’t want to show their emotions. I realised when I spoke about the story with the actresses – Sophia and Geraldine said, “but he never says thank you to them for organising it all, he never says thank you?!” So he’s very selfish, but at the same time he is alive. And that was the whole idea of the film, and the paradox of the film: to be on the side of life. This man, who loved life so much, he wants to die because he loves life. That’s the paradox. So each time he could have some moments of fun, of joy, it was important, to be on the side of life.

Tell us about this absolute wonderful cast that you’ve put together. In particular, I know you’ve wanted to work with Sophie Marceau for a long time and finally, the planets aligned on this film. And then you’ve got André Dussollier as her father, Géraldine Pailhas as her sister and even Charlotte Rampling appears as her mother.

Sophie: it was like a dream. Because, you know, she’s very famous in France. We grew up with her in France, we knew her from when she was very young in La Boum. So for me, it was important to have a popular actress to be in this story, to be involved in this complex relationship between all these characters. So I was very happy when Sophie agreed to make the film. I think the story resonated in her own life – her relationship with her father, with her mother – so she was totally involved and it was great to work with her. For André, he’s a very professional actor, he wanted to know everything about having a stroke, and he had some makeup put on each morning, three hours of makeup, but he was not afraid, he loved all those kinds of things. And actually, it was very funny for him to play this part because he’s always in a bed with beautiful girls around him and he says say mean things to everybody. He actually had a lot of fun! He loved to play this character.

On that note, how did you find the logistics of filming? It must have been a challenge at first to think about how to film a guy in a bed within the room of a hospital in a varied way, and also ways to expand out of that location and play with different scenes.

Actually, I was lucky because they were a rich family. Because if they were a poor family, I would have had to stay in one room of the hospital during the whole two hours! But because they were rich, they had money to move to a nice hospital. And for me, in terms of the mise-en-scène, it was better, because it would have been a nightmare to stay the entire film in one room, with one bed, in the same place, and to shoot always in the same way. And that was actually something else I discovered making the film: the injustice for people who want to die who don’t have money. You realise it’s unfair, because only rich people can organise these kind of things. If you don’t have money, you have to wait for your death in a very bad state.

Can you also talk a bit about the tone of the film, because of course you could see this as very heavy subject matter, but it’s injected with levity and moments of deadpan or black humour in spite of the situation. Was that an important tone to strike?

Yes, it was important. It’s what I said before, it’s because it’s on the side of life. And life is like that. I had in mind this situation when you go to a funeral and you suddenly get the giggles!

In that sense, what do you hope that people will take away from watching it because, as we’ve said, this can be an uncomfortable topic for some people to contemplate. But perhaps by watching a film like this, they find different ways of thinking about death.

I think the film is a good experience in it allows us to think for ourselves: what would I do in this situation? Would I be able to help someone close to me to break the law? I think you can share in the emotions of the characters and it can help you to answer that. To prepare yourself for this end, which will happen for everybody. We don’t have a choice. There is a French philosopher, de Montaigne, who says, “in order to accept death, you have to think about it every day”. But you can do it without suffering, you know? The more you prepare, the better off you will be when you’re faced with that situation.

Do you think that recently we are seeing more and more films that don’t shy away from these taboo topics and show a more frank depiction of end of life, death and disease? I was thinking of Gasper Noe’s Vortex and Mia Hansen-Løve’s One Fine Morning.

Ah yes, and Amour. Well, I don’t know. It could also be since the pandemic, but I actually started making the film before the pandemic. I can’t answer you because I don’t know.

Can you tell us what you might be working on next?

I am going to release a film in France which is an adaptation of Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant. I’ve made my own adaptation called Peter van Kant. So Petra becomes Peter.

Fantastic, I can’t wait to see it. Thank you so much for your time.

Thank you.

Sarah Bradbury

Everything Went Fine is released in select cinemas on 17th June 2022. Read our five-star review here.

Watch the trailer for Everything Went Fine here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS