Edvard Munch: Masterpieces from Bergen

Influential Norwegian painter and printmaker Edvard Munch (1863-1944) would seem fated to be forever entwined with the existential angst of his 1893 masterpiece, Scream. A new exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery will provide a more nuanced understanding of the modernist. In 1906, an industrialist compatriot of the artist, Rasmus Meyer started to purchase Munch’s work, seeking to form a collection representative of the evolutionary stages of his career. Ultimately this would lead to the creation of the KODE Bergen Art Museum in Norway that boasts one of the finest assemblies of Munch works in the world. The Courtauld’s compact but revelatory gathering of 18 paintings from this collection promises to bring into sharp relief the impact of the Norwegian’s artist influences and his own remarkable creative output.

A surprise awaits the public in the opening room. Spring Day on Karl Johan (1890) sees the artist capturing Oslo’s main boulevard in an impressionist style, suffused with a Monet-like sense of light with brushstrokes recalling those of Seurat. The Courtauld’s new layout enables a visitor to enter the temporary exhibition space via the impressionists and post-impressionists Munch was exposed to in Paris. Morning (1884), painted by the Norwegian at 20, depicts a young woman gazing out of a window as she dresses. When exhibited in Paris at the Exposition Universelle in 1889, it received a mixed reception but testifies to the artist’s then notably physical handling of paint, alongside his experimentation with light to shape form.

Munch’s work is shown to be undergoing rapid transformations. Only two years after Spring Day on Karl Johan, one finds him producing the nightmarish vision of Evening on Karl Johan at the opposite end of the same street. Brooding tones generate a psychologically intense scene that draws on the dramatic effect of the recently installed electric street lighting of Oslo (then Kristiana). A haunting horde of mask-like figures confront the viewer while a silhouetted figure heads in the opposite direction. The artist depicts himself as an isolated loner, searching in vain for a woman he is infatuated with. Then living in Berlin, his Frieze of Life series would greatly influence German expressionism.

Summer Night. Inger on the Beach (1889), Munch’s portrayal of his sister in the coastal town of Åsgårdstrand, is considered a major personal breakthrough. Departing from earlier impressionist concerns with multiple light effects, he starts to simplify the main compositional elements. Inger’s luminous white form is at once set against and yet unified with the boulders, expressing an overriding mood. In House in Moonlight (1893-95), another work painted in Åsgårdstrand, where Munch had a summer house, one finds the artist evoking Nordic summer nights. There is the suggestion of an emotionally charged encounter between a white-aproned figure and a man caught in shadow, believed to reference an affair he had conducted with a married woman called Millie Thaulow.

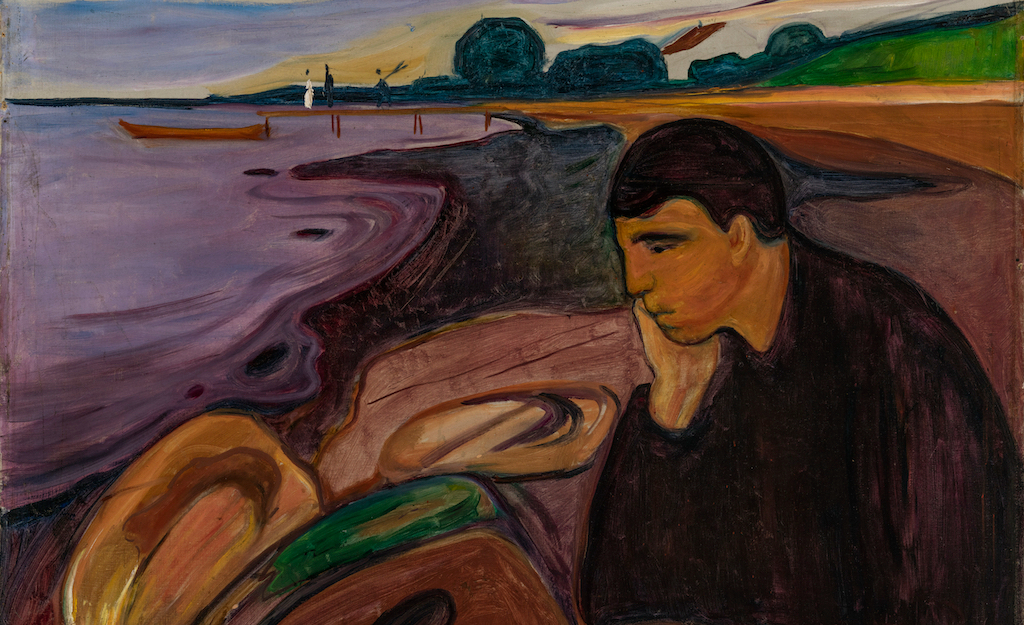

Sexual tension continues to rear its head. The Courtauld’s poster work, Melancholy (1894-96) features an isolated male figure in profile, sitting alone on the shore. There’s a pervasive sense of emotion generated by the artist’s distillation of form and colour as the flowing lines lead the eye to the assumed cause of his heartache on the horizon, where she stands, dressed in white, with another man. The symbolistic Woman in Three Stages (1894) shows a bride in virginal white, a naked flame-haired femme fatale and gaunt old woman, all set against a brooding Norwegian landscape. On the far right, a male figure hides among the trees. Munch examined the destructive potential of romantic relationships, which also becomes apparent here in the post-coital Man and Women (1898). Never to marry, the artist had a string of love affairs, regarding the female of the species with a mixture of desire and dread.

Traumatic events such the death of his mother from tuberculosis (when he was five) and the demise of his sister Sophie from the same disease had a profound effect on him. His ill health as a child was followed by alcoholism and depression in adulthood. At the Deathbed (1895) relates to Munch’s recollection of Sophie’s death. The group dressed in black overlooking the bed, where his sister lies, are merged together by a dark shadow set against a red wall. Symbolic colour heightens the emotional intensity. Four Stages of Life (1902) is an allegorical depiction of the human life cycle. The young girl in the foreground looks out at the viewer with an innocent smile. Munch uses the same pictorial device in Children Playing in the Street in Åsgårdstrand (1901-03): here, diluted veils of colour on first impression create a cheerful mood, until one becomes transfixed by the melancholic intensity of the girl’s blue-eyed gaze alarmingly close to the picture plane.

Chronologically the last work here is Munch’s Self-Portrait in the Clinic (1909), painted following his treatment for a breakdown in 1908. He adopts a vibrant, loose style, portraying himself in his suit using broken lines of pure colour, apparently at times taken straight from the tube. The fact that Rasmus Meyer was able to buy the painting directly from Munch in the year of its creation testifies to the high esteem in which the artist held the industrialist as a collector. The exhibition ends with sun-drenched images of vigorous young bodies in Bathing Boys (1904-5) and Youth (1908). Visitors expecting visceral depictions of psychological torment and trauma will find such Munch tropes in abundance and yet leave with a more rounded appreciation of this hugely progressive modernist.

James White

Edvard Munch: Masterpieces from Bergen is at the Courtauld Gallery from 27th May until 4th September 2022. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Watch a trailer for the exhibition here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS