“He used to spit at the audience, roll on the ground, he did, in fact, hump that plastic dog – he was the original punk rocker”: Baz Luhrman, Tom Hanks, Austin Butler, Olivia DeJonge and Alton Mason on Elvis

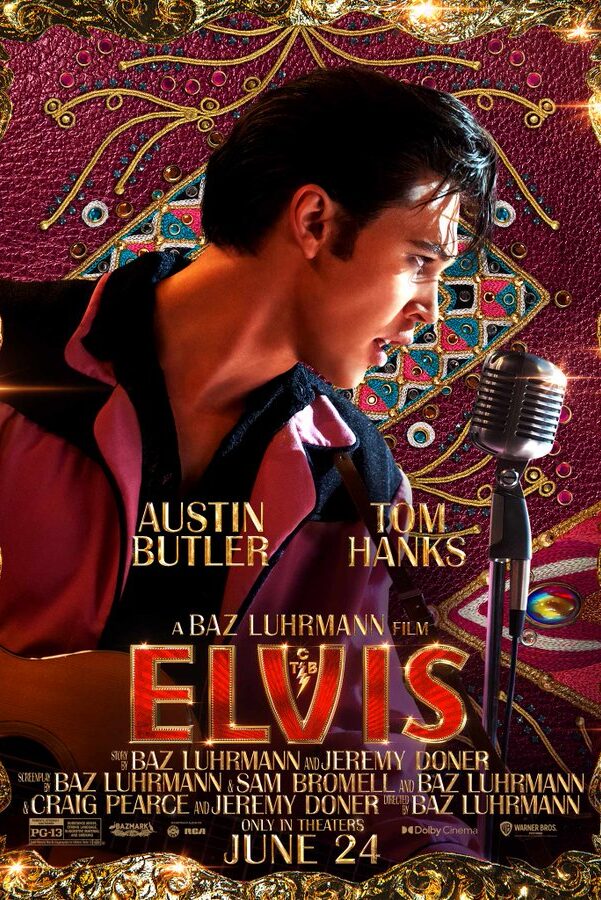

In case anyone had any other expectations, Baz Luhrman’s Elvis Presley biopic, Elvis, is so very “Baz Luhrmann”. Bringing to life the story of one of the most famous faces and voices on the planet, from his humble beginnings to worldwide fame, Elvis’s life gets the same treatment as Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Moulin Rouge! and The Great Gatsby, a kaleidoscope of colour and a jukebox of musical delights charting his influences and evolution. It’s an immaculate sensory feast in every frame.

Acting under heavy prosthetics and a heavier Dutch-leaning accent, Tom Hanks is virtually unrecognisable as Colonel Tom Parker, the man the film ambivalently presents as both the driver of Elvis’s fame but also the root of his downfall, while Austin Butler is fully transformed into the Elvis “the pelvis” Presely, even nailing the ever-bolder hip-shaking moves and – most impressively – all the vocal performances in the first part of the film.

The furious pace can mean many moments fail to delve deeper under the movie’s glossy surface sheen, with some of the emotional beating heart of Moulin Rouge! and streak of blacker-than-coal humour of Strictly Ballroom somewhat missing. It does attempt to highlight and give credit to how Elvis’s upbringing in Black communities influenced his music, as well as how he was the original punk rocker in terms of his taboo-busting performance style, and it touches on the forces that led to his ultimate demise. Butler, though, wow… Faultless.

The Upcoming had the pleasure of hearing from the cast and creatives behind the movie, including Luhrman, Hanks, Butler, Olivia Dejonge (who plays Priscilla Presley), Alton Mason (who plays Little Richard) and the producers, Gail Berman, Catherine Martin, Patrick McCormick and Schuyler Weiss, at the press conference at the Cannes Film Festival 2022, the day after the film’s premiere where it received a standing ovation. Here are some of the highlights of the Q and A.

Let’s start with what happened at the screening yesterday. It was crazy. Baz, can you describe the emotion you felt?

Baz Luhrman: Well, like I said yesterday, when I made my first film and we were dropped by the distributor, Cannes saved our cinematic life. And I think, standing there, that emotion was for our film. Because our film is made for one thing and one thing only: to bring audiences into the theatre. It is a theatrical film; we meant to make it theatrical. And I think that that ovation was as much for the film as it was for the idea of cinema, of the theatre. And I was in a theatre full of love for cinema. It meant the world, and Cannes, I think, has saved us once again. That’s what I think.

Let’s continue with you Baz. A very simple question: why Elvis?

BL: Well, I’m a great admirer of when Shakespeare takes a historical figure but explores a larger idea, and also one of my favourite films growing up was Miloš Forman’s Amadeus. Now, is Amadeus really about Mozart? Or is it about jealousy between Salieri and Mozart and him saying, “God, I did everything right. And put all that talent in and that horrible, grotesque person…” – it’s about jealousy. And I wanted to take Elvis, his life, and really respect him and his fans and the love people have for that character, but also show that it’s an exploration of America in the 50s and 60s and 70s. And the relationship between the “sell” and the “art”, the show and the business, the snowman and the showman. So that’s what the big idea really is. But on the way there, through the research, living in the South, being embraced by Graceland and our whole journey, I learned about Elvis “the person” in the most unexpected way. That will stay with me all my life – that you can think one thing about someone and come out the other end and realise something completely different.

Speaking of the snowman and the showman. Tom, you have never been afraid of ambiguous characters or shades of grey in the way you play your characters. This one needed that – to be on the border of good and bad. How did you play that ambiguity?

I am a professional. I am paid to put on different people’s clothes and pretend to be somebody else. I pay the rent… So, I feel lucky. I owe all of this to this man, Baz Luhrmann. He came and sat down with me… all I knew was, “Baz Luhrman would like to talk to you about Elvis”, and I thought, “Well, that would be a waste of time”, but when he came in he said there would have been no Elvis without Colonel Tom Parker, there would have been no Colonel Tom Parker without Elvis. It was a symbiotic relationship. I did not know what Colonel Tom Parker looked like; I had never heard his voice. I thought it would be a tall, stentorian guy in a hat, full of bombast, and, instead, he turned out to be this rather ingenious pimp of the carnival, who seemed to enjoy robbing a little kid out of an extra 25 cents for a photograph of Elvis just as much as he enjoyed robbing a casino in Las Vegas out of $25 million. It was the same exact pleasure that he got – not from the amount of money, but from the exchange. Baz talked about the Colonel as this great “carnie”, knowing that the carnie’s job is to bring people to the glittering lights on the outside of town, promise them something they’ve never experienced before, and then almost give it to them, at a cost. And when he said that, I think the conversation lasted seven minutes until I said, “I’m your man. Now please show me a picture of what the colonel looks like”. Then he showed me and I thought, “Oh, my God, what have I done?”

BL: True story, true story.

Now, the showman. Austin, what does it take to become Elvis?

Austin Butler: A lot of work! I basically put the rest of my life on pause for two years, and I just absorbed everything that I possibly could. And I just went down a rabbit hole of obsession and broke down his life into periods of time where I could hear the differences in how his voice changed over the years, and how his movement changed over the years. I just spent two years studying and trying to find his humanity as much as I could through that. Because that’s the tricky thing: you see Elvis as this icon, or as the wallpaper of society, and finding the way to strip all that away and find the very human nature of him that was deeper than all of that – that’s what was fascinating for me. And the ability to get to explore that was just the joy of my life, for sure.

Olivia, we all have our own vision of the Elvis story and the people who were around him. Did you feel there was a responsibility, firstly to the real-life characters who lived the story, but also to us because we have our own vision of it?

Oh, absolutely. I think there is, certainly, especially when somebody’s still alive, like Priscilla is. And, obviously, she’s here supporting the film. There’s always that energy of feeling like they’re on your shoulder constantly watching, and I think you’re always going to grapple with whether or not you’ve illuminated something real and human in them. Absolutely, I think there’s a huge responsibility. I think that she is such a key part of this narrative and such a key part of his legacy, especially today. Everything that she’s done, obviously, since they parted their ways, is such a testament to their love. And, absolutely, there’s a responsibility. And the fact that she’s happy and supporting the film here – it means the world.

The world of Baz is visually crazy. What does that mean for you guys as actors?

Alton Mason: I think it’s a super big pleasure being a part of his world, because it’s so powerful. And it’s so spiritual and it’s gravitating and ascending. So, when I first met Baz, it’s kind of like I got sucked into that vortex. And I think, as an actor, you should surrender to it – surrender to that feeling. I grew up in Arizona and I have soul tied to the Southern state because I’m from Shreveport, Louisiana, on my dad’s side. So, I think developing that world and creating the ambience with the film really resonated with me on a spiritual level.

TH: We owe Alton a huge thanks because his performance as Little Richard allowed the audience to applaud the musical numbers. The first applause in the movie came from Little Richard! Rightly so!

This is a question for all the producers, but maybe we’ll start with you, Catherine. At the beginning of the film, there was a split screen with eight different images. Do you guys ever try to tell Baz, “Maybe you should not do this much…”?

Catherine Martin: I don’t think that would work. I think that the fantastic thing about working with him for 30 years is that he always pushes you beyond what you think is possible, or what the audience may or may not – you’re on the edge of the new. And what’s exciting is often you are examining historical figures, or history, but his lens is always on the future. And so, to me, what’s exciting is – I just watched the movie the other day, and I’d been very irritated by him during the day, as you can imagine a husband can be, and I watch the movie analytically when I help and work on the different visual aspects of the film, even in post-production, and I watch it without sound and I’m looking at: that shoe’s terrible, there’s a wrinkle here, that backdrop’s terrible. But when I saw the movie completely together with the music, I felt that it came together as a piece of transcendent poetry that I had never expected, and I’m amazed that he can still surprise me after 30 years.

BL: Well, she surprises me after 30 years every day too!

Patrick McCormick: I would only say that Baz’s film language, his cinematic technique, is very distinguished, and we’ve seen it progress film after film. And I thought this film was the best and most fulfilled manifestation of that signature style of cinematic language. He creates information and music and feeling with images in these collages and the simultaneous screenings, these transitional moments. We had an expression in the movie called “poetic glue”, and there was more of it in this movie, and more successfully applied in this movie, than I think any of us has ever seen before.

Gail Berman: When I first saw the film, from the very first frame, I knew it was a Baz Luhrmann film – the second it starts. That is an extraordinary thing to say. This filmmaker, from the moment we watch the screen, is in control of everything. And all I can say is that that was the thought from the get go: “How does this man take on that challenge and make it his own?”. And I think he’s done it with such panache and such grace, it’s been a pleasure to watch it.

Schuyler Weiss: As Baz talked about using a life as a canvas to tell a bigger idea, I think what is so inspiring about working with Baz over almost 20 years is creating a thrilling, huge entertainment – a great spectacle – that also reveals deeper emotions and bigger ideas. So when you have these multiple split screens, when you have this spectacle going on in front of you during the film, you walk away feeling deeper feelings and with lasting bigger thoughts.

Tom, you’re not well known for playing unlikeable characters in your career. Can you elaborate on how you prepared for this role and how you tried to make him a bit likeable?

TH: I think the Colonel, as I have heard from tonnes of anecdotal information – he was, in fact, a delightful guy. He lit up every room that he came into. Priscilla and Jerry themselves have told me that they wish he was alive today. Was he a cheap crook that played fast and loose with money? Yeah, he was a little cheap crook when it comes down to that. But they worked that all out to everybody’s satisfaction. He was a man who brought joy into everything he did, along with just a little bit of larceny. I’m not interested in playing a bad guy just for the sake of, you know, “Before I kill you, Mr Bond, perhaps you’d like a tour of my installation?”. That’s okay, I get it, but I think that’s for other stuff. And what Baz tantalised me with… right off the bat it was: here was a guy who saw an opportunity to manifest a once-in-a-lifetime talent into a cultural force. He saw that, he knew that about Elvis the first time he saw Elvis’s effect on an audience.

There’s a moment, that is very much taken from fact, of the Colonel seeing some guy on=stage doing something he’d never heard before – wiggling like crazy, without a doubt a powerful force – but he wasn’t paying attention to what the man was doing on stage. He was paying attention to the effect on the audience that was watching him. He realised that that guy was forbidden fruit. And you can make an awful lot of money on forbidden fruit, but you can also turn that into something that is much more of a cultural exchange. I give Colonel credit for doing that very thing. And I also will give him the reality of being – the amount of ways that Colonel Tom Parker cheated people out of nickels and dimes and dollars is extraordinary. And, by the way, I’ve incorporated some of those in my own life now… You learn a little something from every role, you know? But as far as… no one knew of the Colonel’s background. And there are some extraordinary tabloidy, melodramatic stories about why he left Holland and how he did. I like to think that, yeah, he was running away from an aspect of his past. He wanted to get out of his small town, he wanted to work up in the big time. And who among us wouldn’t jump at an opportunity to do that very thing? I don’t know if we have to change our name, particularly. But as soon as someone said, “I’m going to make you an honorary Colonel, Tom Parker”, he said, “Well, guess what I am now: Colonel Tom Parker!”. And that’s a mercurial and brilliant man, who at the same time, made sure he lined his own pockets.

I heard this great quote about Colonel Tom Parker in 1956. Someone said, “So why is it that you latched onto this, and what magic are you working with Mr Elvis “the pelvis” Presley?”. He said, “Well, I tell you last year, my boy had a million dollars worth of talent. This year, my boy has a million dollars.” And I’m gonna say about 10% of that was in Colonel Tom Parker’s pocket. So, that all worked out. God bless America, and who wouldn’t jump ship in order to have an opportunity to do that?

We talk about rock’n’roll all the time, but the movie pays an incredible tribute also to blues, to soul music and especially to Mahalia Jackson. Could you say a few words about those rhythms, as well and their importance to Elvis’s story?

BL: Yes, I’ll tell you: homework, research, the depth of research. I want to make an acknowledgement of my team, because I don’t work alone on anything. And when it comes to research – I have a research team and we go and live there. We lived in Memphis, I had a space at Graceland. Whatever the character did, we do. And we do academic research, and so on and so forth. But we do research in the field, and one of the great revelations was – I wanted to find out about this period in which Elvis, after his dad goes to jail, ends up with his mum in the south, and Elvis and his mum are so poor – dirt-poor – that they end up in one of the few white-designated houses in the Black community because they’re so poor. And I even had it digitally mapped, I lived there, I had it digitally mapped, and the streets were changed and everything. And there was a gentleman alive, who passed last year, called Sam Bell, who’s not a lot in documentaries. And we tried to find him: no response. We’ve tried to get him: no response. And I even sent a FedEx message to his house in Tupelo and I go down with my team and we’re there and it was our last few days, and the FedEx is sitting on the front door. And I go, “Look, he’s obviously passed, it’s too late. This is the last lead”, and one of the younger guys says to me, “So let me get this right – we’re gonna come all the way here to Tupelo and you’re not getting out of the car?”. Because I’m a bit of a scaredy-cat to be honest. I got out of the car and I went up and there were cobwebs around the door. It was clear there was nobody in the building. So the young research guy said to me, “Well, let’s just go around the back.” I’m like, “Oh, my God. All right, I’m now breaking and entering…”. So I go around the back and an old woman comes out and says, “Oh, Sam’s still alive – he’s in hospital. But he’ll be back next week”.

I meet Sam Bell. He’s a beautiful, older African-American man, and he tells me stories… He points out his grandparent’s backyard… I mean, Elvis had to walk, every day, as a child, through the streets of the Black community, past the Black school, to get to the White community. But he said, “We became fast friends” – it’s in the movie, they were a gang. And they ran off to juke joints and saw Big Boy Crudup, and they went to Pentecostal tents. And that led to Elvis later in life being one of the only White faces at Club Handy, says the owner of Club Handy, on film. And, you see, this is the thing about young people: they absorb all kinds of things, especially someone with a big hole in their heart like Elvis, who had a twin that he could never live up to, who had conditional love from his mother, who was always searching and seeking and absorbing. I grew up in a small town. I knew what it is to look around and go, “Oh God, how should I wear my hair?”. But the point is, he absorbed these things. And he also mixed it with his love of country music, white gospel. He absorbed it and mixed it. And I think the most important thing in this film is to show that a young kid, just like Eminem, grew up in a Black community. Young kids don’t care. Their personalities are formed by what’s around them and what they absorbed. So the music that came out of Elvis was music that he absorbed in his friendships with emerging Black musicians, who weren’t famous: BB King, all these things. You see, we do our homework. So I know these things to be true. His love of gospel – you know, to the day he died, he would stay up at night, after two shows, with The Sweet Inspirations, mother of Whitney Houston, and sing gospel music to the morning, because that was his safe place. That was where he felt safe.

So, to your question, and I know I took the long road around, right? It’s so important to show… you can make all the rules you like, but kids growing up are gonna absorb things around them, and they’re gonna make something new. And that’s really what Elvis was. He went out of his way to say, “I never invented rock’n’roll. I just put my spin on it.” He went out of his way to say, “Don’t call me the King. I’m not the King. He’s the King”. He went out of his way to say, “Let’s face it, I’ll never sing as well as BB King”. He was an incredibly sensitive, spiritual guy. That’s what I discovered, above and beyond everything else. Say what you like – he was a deeply spiritual being. Long answer, I know, but you’ve seen my movies, right?

How involved were the Presley family and estate in the making of the movie? Was it a very close collaboration and what was the response of Priscilla Presley when she first discovered the movie?

BL: Okay, well… Early on, I got to have several lovely dinners and meetings with Priscilla. And I met with Priscilla, I met with Lisa Marie and Riley, then Covid happened. I was constantly having to rewrite to try and keep all these balls in the air, and also to truly find the movie. And we both went through personal things, which I’d rather not go into. So pretty much after those initial get-togethers, I was unable to engage in the way I normally would. I have no fear of actually reading scripts and all of that going along. But a long time passed. And I understood absolutely the trepidation, anxiety, maybe even scepticism, of what we would do with the story of her husband, of Lisa Marie’s father and Riley’s grandfather. And there was trepidation; I just couldn’t get there. If I just didn’t keep the balls moving, they would fall on the ground. And so, really late, much later than I would ever like it to happen, I had to screen probably about the third or fourth cut of it. You have to understand, too, that you have to test, and then there’s budgets and visual effects and all that sort of thing…

Priscilla had fear about seeing it too. So much has been said about the icon, Elvis, like he’s wallpaper – so many things that are just not true. What will we do? Will we lean into this and that? Criticism of anything you make, I’m used to it. And just like Elvis said, critical people have their job. And some do it well, and some not. I like critical people who do homework, because I’m big on homework. But no critique, no review was ever gonna mean more to us than the review of the woman who was married to Elvis Presley. And I can’t tell you how our stomachs felt when she went in with Jerry to see that movie. I can’t tell you how long that two hours was. And I happened to be caught on a plane. When I landed, I was on the phone, and there was a security guard with Priscilla, who was crying. And I said, “What’s going on?” and she said, “It’s because of Priscilla’s state.” And I was like, “Oh God, what have I done?”. And then she wrote a note. She said, “I’m sorry it took so long, I just had to gather myself”, and she said, “I just wasn’t ready for that.” She said about Austin: “Every breath, every move, the spirit of the person, the humanity, the man, not the icon, not the guy in the trashy book, not the person that someone thinks they know because they’ve made it up in their head…” she said, “If my husband was here today, he would look him in the eye and say, ‘Hot damn, you are me’.” And then, with Lisa, she had the screening and she looked up to the sky as I took her to the car, and I thought she was gonna say, “I can’t put it into words”, but she said “value”. And Jerry said it too. And Priscilla said it too. I think it’s important to them: he was a father, he was a husband and a grandfather, a person. And they have children and their children will have children. And the greatest review I’ve ever got in my life is from them saying, “Now there’s something they can look to”, and, in their view, is the truth of the humanity of the man. So that will be the best review I know I’ve ever had.

Austin, what was the main challenge for you in embodying your character?

AB: It’s such a tricky thing because, when I first started, I put these unrealistic expectations on myself that somehow, if I worked hard enough, I could make my face identical to Elvis – his face. And that my eyes would look exactly like Elvis – his eyes – and you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. And I realised that at a certain point that becomes like going to the wax museum, and what is really important is that his soul comes out. And so, just like I was saying about stripping everything away, it was finding the balance between getting as specific as I possibly could – and that meant just in this research, I would watch one clip of, just to take an example, the Milton Berle [show], Hound Dog: I watched one second of this clip over and over and over and I’d look at what his eyes were doing, look at the angle of his head, look at what his hand was doing, and try to find it exactly, and practice that until it was in my marrow. And then the tricky thing is being able to be there on the day and have it feel like it’s happening for the first time, and that it’s spontaneous and it’s actually alive. And the reason why he moved in that way and why he spoke that way and that meant finding his inner being. But then it’s like spinning plates because you want to go back to the specifics. And so it was this constant back-and-forth.

Somebody asked me yesterday: “Did you watch playback when you were filming?” and I said there were certain moments, like watching Hound Dog, where if we did one take and then I went back and I watched it and I thought, “Oh, what’s wrong? I’m doing too much.” So then it was: strip it back, strip it back and try to get to the point where… you have to get through the nerves of it and then just feel the life. And yeah, Baz read Priscilla’s text message to me when we were driving to dinner, just the two of us in the car, and it just brought tears to my eyes because, ultimately, there’s never been a person who I’ve never met that I’ve loved more than Elvis. You know, I’ve lived with him now for three years. So the feeling of doing him justice – justice to his legacy – and really bringing life to this extraordinary man and to make Lisa Marie and Priscilla and Riley and the entire family proud, I could not be more overjoyed and I just feel over-the-moon about that.

Coming to the use of music: Baz, one of the things you’re very famous for is fragmentation of tunes, integration of mashups and all those elements. You had a freedom and a liberty to do that with Elvis’s tracks. Can you talk about the challenges of doing that and still making it sound both contemporary and classic?

BL: Great question. I mean, people say what they say – that I make my movies for now, but for the future too. I want them to go on. Now, one of the most important rules of the kind of language that I do is immense historical research. I have a label, House of Iona, with RCA, I’ve had it for years. So I had access to unbelievable takes of Elvis material you’ve never heard him sing: the Beatles, things like that. But one of the things that’s always important – and I did this on Gatsby, whether you agreed with it or not, but when Fitzgerald wrote and basically put an emerging Black street music called jazz into his novel, as a relatively young writer, he was criticised for that, because jazz was going to be a fad. It was sort of like early hiphop. I mean, I did The Get Down, working with Flash and Herc. They thought that music would never get outside the Bronx, right? They were kids, right? And now it’s the biggest genre in the world. So when I did Gatsby, the whole thing is to respect the music and have the classics, and we have Elvis singing as Elvis. We have Austin singing classic Hound Dog as Elvis, right? But I also want it to be present now. It’s what it was, but then the translation – the idea of, say, taking Black American street music, hiphop, which I did with Jay Z on Gatsby, is: what did it feel like? What did that music feel like? Because as terrific as Hound Dog might be – it’s charming, at best, you play that song, it’s charming or it’s got a good beat. Now, by the way, Hound Dog was written by two white Jewish composers, Leiber and Stoller – it was covered by Big Mama Thornton, which has done so wonderfully and played so wonderfully by a gospel singer we discovered in the South, Shonka. Now when she says the lines in that song, they were some sort of edgy, salacious, rude, unacceptable-in-polite-society way of saying, “Listen, you’ve been expletive around, right? Don’t come sniffing at my door and expect expletive, you can hit the expletive, expletive road, Jack”. So I have that song in there. But as Austin’s walking down the street, Doja Cat is translating it into rap, so that younger audiences, who really don’t know Elvis (except for Lilo and Stitch, right? Or maybe there’s a video game, “He’s that guy in the white suit”) understand how edgy that music was – what that music felt like at that time. So it’s what it was, but what it actually felt like. And so that’s why I do it – not to be groovy, or to have a groovy album or whatever – I do it because I want a younger audience to feel what it was like. Elvis’s early recordings are lovely. They’re lovely, but they’re polite and charming. But I’ve got a recording of an interview with Colonel Tom Parker, it’s a very rare recording, and he’s talking in the foreground. And in the background, you can hear some Country and Western singers. And then you hear this keening – keening is the sound of screaming, and Elvis comes on stage. And everything I’ve read, even speaking to people that had seen him – I mean, he used to spit at the audience, roll on the ground. He did, in fact, hump that plastic dog. I mean, he was the original punk rocker. And the music was so much more aggressive, and feedback, and louder and scratchy and crazy. So that’s why Russwood – everything at Russwood has a historical reference, but we moved it all into one concert. But that performance at Russwood, that sort of punk rock performance, that’s real. He did that. I just want the audience who don’t care about Elvis, the younger audience, to feel what it was like to be there. So that’s why I do that work.

Unfortunately, Elvis has to leave the building. This is all the time we have. Thank you very much.

Sarah Bradbury

Elvis is released nationwide on 24th June 2022.

Watch the trailer for Elvis here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS