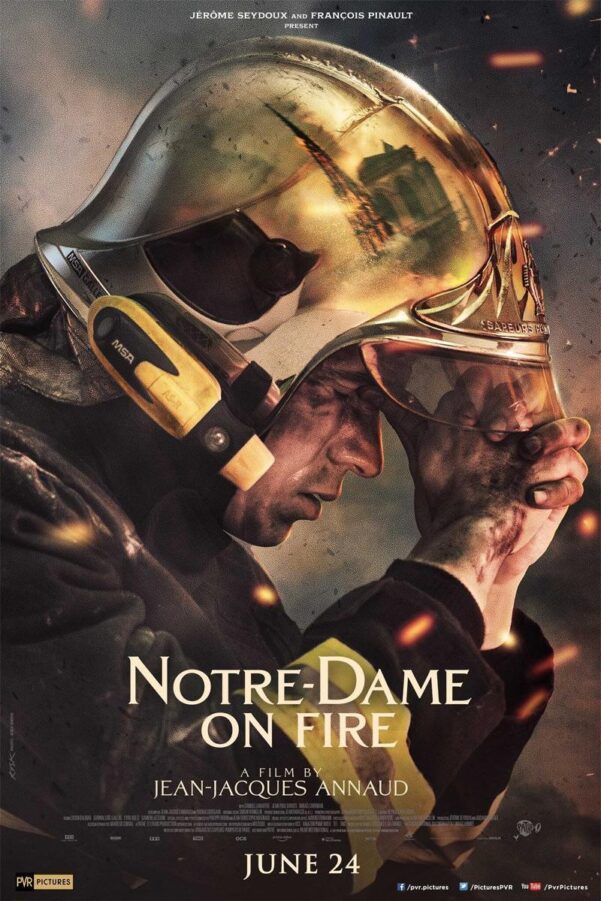

“People today want to go to the cinema to see something that deserves the trip – and the money”: Jean-Jacques Annaud on Notre Dame on Fire

Jean-Jacques Annaud’s (Seven Years in Tibet, Enemy at the Gates) Notre Dame on Fire takes audiences right up close to the events of 15th April 2019, when the world watched in disbelief as Paris’s iconic 850-year-old cathedral went up in flames. Using an ambitious collage of real footage, built sets lit on fire and shots from inside real cathedrals, the filmmaker has gone to painstaking lengths to bring the extraordinary reality of how the blaze unfolded and the heroic steps that would be needed to defeat it to the big screen.

The Upcoming had the privilege of sitting down with Annaud to hear about the extensive research and preparation that went into executing the large-scale project, how he personified the cathedral and the fire as characters in an almost perfect story of suspense and action, and how he hopes the movie will prompt other nations to invest in their ageing buildings, which hold a special place in our local and global communities that transcends religion.

Hi Jean-Jacques, such a pleasure to be able to speak to you today. Maybe you could just kick us off with a brief introduction to your film, Notre Dame on Fire. What can people expect?

Well, they may not realise that they’re going to see a thriller, based on reality. It’s a thriller, it’s a true story, and I know people love true stories. And I insist on that because what they’re going to see seems impossible, seems untrue. Because it’s so bizarre what happened; it’s a series of mini catastrophes. As we say, in French, mini “faux pas”, like when you put your foot in a hole and it gets stuck. It’s exactly what happened. It’s Murphy’s Law, everything that can go wrong, will. And this is exactly what happened at Notre Dame. It’s a succession of mistakes, incompetence, lack of preparation, life in Paris, and bad luck. And then, good luck. All that seems absolutely impossible, not credible. And the more incredible it is, the truer it is. In a way, it pleases me when people go and they’re not sure what they’re going to see. And by the way, I’ve never had so many compliments on a movie since I’ve been making movies. Because the movie reproduces what happened – but there is a lot of tension. There’s suspense. Although we know the end, we don’t know how we get to this ending. It’s an old Hitchcok lesson: better to reveal the ending right away, because the movie is not about who did it or what, but how did we manage to get to this ending? And I must say that it was extremely rich material. The story, basically, is a very typical story: of a lady, a star, an international star, Notre Dame de Paris, who is going to die. And she has a terrible, charismatic enemy. So, therefore, the great villain – once again as Hitchcock recommends for every movie, get a great villain – the best villain is a fire. Fire is something wonderful when you have it in the fireplace in your house in winter. It gives you light, it’s warm and it’s beautiful to look at. So you have a very photogenic enemy, a villain that is going to attack a beautiful star, internationally known. And the story is also about the poor doctors who cannot assist, who cannot get there. Now, first of all, they’re not warned that it is happening. They’re late because nobody warned them, because of a series of mistakes, and then they’re almost certain not to manage to rescue the star. So, in terms of film structure, it’s quite perfect, it’s the ideal. And we could go quite far away in terms of bizarre events because they are true. You wouldn’t dare otherwise, you’d say, “Oh, no, no, no, I’m going too far here. People will not follow me”. But here, sometimes some audiences are saying, “But is it true?” Yes, it is true! For instance, only 4% of the firemen in Paris, who were all from the army, are women. That day, the first truck that went to rescue the cathedral, had four people inside, all of them very young. They weren’t rich, they were 25. Two of them never had to fight a fire. This was their first fire. And two of them were women. On top of that, they were extremely beautiful to look at. They were very competent. They were the ideal. But I would not have dared to write that if it was not true. But it’s the truth! So you start from there. It’s too good to be true. I’ve done several movies, like Seven Years in Tibet with Brad Pitt for instance, or Enemy at the Gate seven years ago with Jude Law and Ed Harris – they are based on true stories. And I tried to be as true to the real stories as I could. Here, the difference is I could interview 98% of the people you see on screen – who are played by actors, of course, it’s a fiction movie – but, it’s all based on testimony from the people who were there. And it gave me the freedom to go further than I would. Because I would be shy to go so far. That was the excitement of making this movie. And I know this is why it touches the heart of people who see it. Because they guess that if we say it then it’s true, although so improbable, so bizarre, so strange. But that’s the charm of it.

And, obviously, it’s such an ambitious project, not only in terms of it being a real event you are trying to reenact but also the scale of the production. Everything I’ve read about you says that you’re not afraid of anything as a director. So could you give us a bit of a glimpse of the preparation that went into the making of the film, from the first models and research, to shooting on location, to the special effects?

My nickname when I was, I think, the age of two – I was called by my mother, “JJ peur de rien“: JJ is my initial, Jean-Jacques. Peur de rien means “afraid of nothing”. As a matter of fact, I am afraid of everything! Don’t get me wrong. But yes, I think that we as filmmakers have to make movies that are not so easy to make. Because “easy-to-make” movies, you can see those on TV. They can be great. But the ambition of bringing people to a cinema, in front of a large screen – you need to have a show, and a show that has to be visual but also has to touch your heart. Therefore, I feel that having an ambition is a must for a film. If you’re going to say, “Go see my movie, it looks like any other movie you’ve seen in the recent years”. I think I’d prefer to stay in bed instead if it’s to offer that kind of show. Here, it’s true that we had the ambition of recreating an event that was spectacular, that was extremely dangerous and, as you can guess after seeing the movie, in which everything that burns I had to recreate in a soundstage or in the backlot of the studio. And as I could not shoot much inside the real cathedral, because it was polluted by lead, I had to do a sort of exciting puzzle using several other cathedrals, under angles that were reproducing what Notre Dame is. So the good thing was, I knew the cathedral well since childhood, because each time I was coming to Paris from my little suburb, we were going through a railway station and the stop was just in front of the cathedral. And I got passionate about mediaeval art very early in my life. When I was like seven, I started taking pictures of cathedrals all over France. Therefore, I had the idea very early on – I knew that I could have the feeling of Notre Dame in different places. But a lot of scenes – you have a scene from above, that I shot in a cathedral that was built before Notre Dame de Paris, in Sans, all the shots from above were shot in Sans, but the reverse would be shot in Bourg, with the same people. And then another shot would be shot in a studio where I will have an angle against a pillar and the same crowd. So you know, it’s the fun of cinema. I would say the fun of the magic of cinema is to be able to create a place that is a mix of different angles. For a movie that I did many years ago, I remember, Quest for Fire, I shot a wide shot in the Glencoe area in Scotland, then the reverse on the west side in Canada and the east side in Kenya, in the same scene, and nobody saw it, you know, because you’re carried by the action. And here, it was a puzzle: I used four different cathedrals and Notre Dame, I had the privilege to be able to shoot in Notre Dame, and we recreated a lot of ambitious big sets with flames that were 30 metres high and 80 degrees hot – because you cannot get the emotion without actors being in the real situation. You cannot tell them, you know, “you’re facing, not a flame, but a blue screen”, t”he broom that you have, as a matter of fact, it’s going to spit water”. It’s different. You can do television like that, but not a film that will capture your emotions. So yes, it was an ambitious big project. But listen, you know, I think people today want to go to the cinema to see something that deserves the trip, and the money.

I love the fact the film mixes genres: it’s kind of a documentary mixed with fiction, but there are also other aspects which seem to draw on superhero films, as you mentioned with the fire being like the villain, and the cathedral the victim or the force for good. It also raises the issue of it being human error, ultimately, that leads to the catastrophe happening, but it’s a catalogue of errors, there’s not one person you’re putting the blame on, which seems to suggest we all have a part to play in what happens. What do you hope people will take away from watching it?

Well, two days ago, I read an article in the Guardian, the title of I think was “Is Westminster the next Notre Dame?”. This article showed a picture with wires, electric wires intertwined in a place in Westminster. But we know it will require a lot of money to restore it. You’re asking me what I feel people will get out of this film? It’s impossible for me to tell you. Each film is different for each viewer. And it’s the beauty of it. Everyone reacts according to his belief. I tried to be true to life. But you are right on one level, I can see what’s happened in France and in a number of countries now is people have become aware of the fragility of these old buildings which symbolise, not only our nations, but Western civilization. That’s why the repercussions of the fire in Notre Dame went all over the world. People understood that if the Forbidden City is destroyed by fire, or if the pyramids in Egypt are bombed by an atomic bomb, it’s a disaster for our culture, for our beliefs. we need roots. And Notre Dame was that for people. It’s far above religion. It’s not only the Catholic people who were crying that night. People in China were crying, the Orthodox were crying, the people in Jerusalem were crying. Because it’s a universal symbol. And now on a practical level, a lot of those buildings now changed their equipment, because they understand through the movie that the accumulation of details can end up in a disaster. We were lucky that it was a positive ending, a happy ending. In fact, I would not have done the movie if there were people badly injured or dead, I would not have done the movie if the treasures in the cathedral were not all in a safe place now. And if I look at the positive aspect, this fire made such an impression on people that there is more money now to rebuild this cathedral in the proper way. There was not enough money to do it before. And it’s not only for Notre Dame: people around the world have become aware that those buildings are important for the stability of life, that it is important to have a mosque or a church in the middle of your village. Because it’s the permanence that you require, that you need. And in Italy, in Portugal and Spain, they’ve been watching the movie and they say, ‘Well, we have to do something to make sure that this will not happen to the Alhambra”, for instance, or to the Colosseum. And that’s an aspect that I didn’t anticipate when I started the movie, of course, but I’m happy that it can have this dimension.

I think that’s all we have time for but can you quickly tell us if you might be working on another project already or not yet?

No. Well, listen, you know, I remember François Truffaut, this French director, used to say that directors don’t quit the movie, it’s the movie that abandons them. And this movie is still with me, it’s not abandoning me yet! It’s going to soon though and then I will have time to undertake something else.

Wonderful. Well, thank you so much for sharing all that with us and can’t wait for everyone else to have the opportunity to see your film.

Thank you so much.

Sarah Bradbury

Photos: Courtesy of Pathé

Notre Dame on Fire is released in select cinemas on 22nd July 2022.

Watch the trailer for Notre Dame on Fire here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS