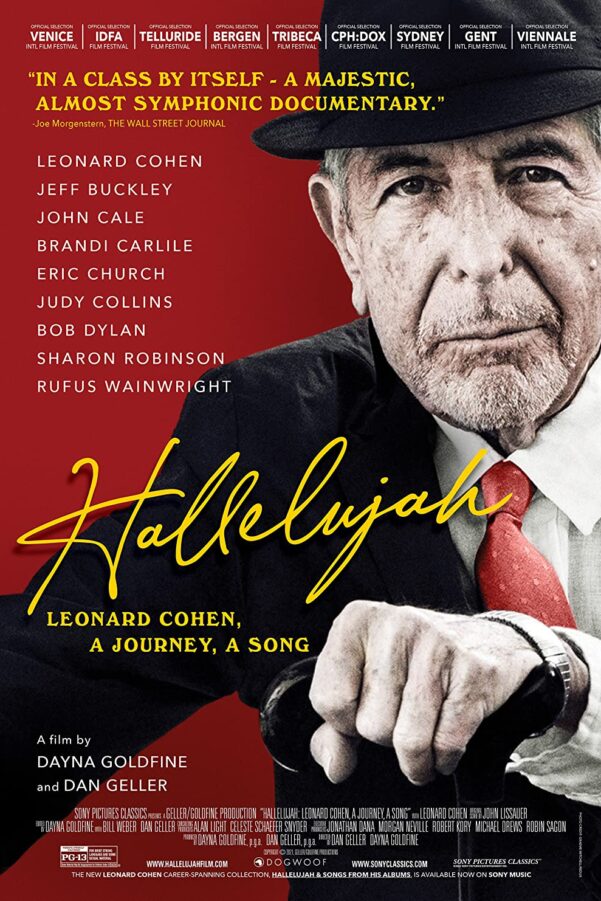

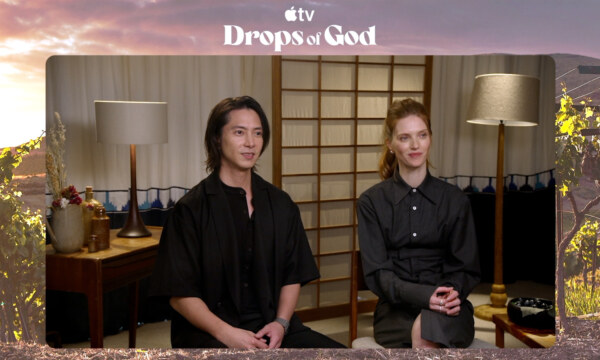

“We wanted people to understand Leonard Cohen, the man”: Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller on Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song

The life and career of Leonard Cohen is one of popular music’s most enigmatic stories. Having never written a song until the age of 30, while his most successful contemporaries were already in the realm of global superstardom in their early 20s, Cohen carved a career for himself which was congruent with the romantic ambiguity of the man himself. For Cohen, songwriting was always more than simply the search for a great melody – although it is a search that was, more often than not, successful – it was a vessel for deeply personal meditations on spirituality, relationships, sex and death.

The culmination of this often painful search for meaning and truth in Cohen’s work was his magnum opus, Hallelujah, from the 1984 album Various Positions. It is through this song, which has been immortalised in popular culture in the years following the release of its original iteration, that documentarians Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller seek to unpick the life and artistry of Cohen, a song whose content and troubled history in many ways mirrors the unconventional arc of his career.

This was a film I was personally keen to cover as I have very fond memories of my mother listening to I’m Your Man on what seemed like repeat! We also attended his 2008 concert at the O2 Arena in London, so I have very fond memories of Leonard Cohen’s music.

Dayna Goldfine: You know, I always love hearing which song or album people grew up listening to on repeat!

When did you first become aware of Cohen and his music?

Goldfine: I would say I became aware of his music first through other people covering it, whether it was Judy Collins doing Suzanne or Jeff Buckley, of course, doing his version of Hallelujah. I feel like the first time I was really paying attention to Leonard Cohen and wanting to know about the man and his career was after we saw him, Dan and I, which was probably 2009 or 2010, on the same tour that you saw him on. He played at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, and a couple of songs into that show, I was a Leonard Cohen convert.

Dan Geller: I knew a couple of those, if you want to call them, “hits”. Marianne and Bird on a Wire I remember knowing, and Suzanne of course, although probably through Judy Collins at first and not through Leonard Cohen. But he wasn’t as much of a figure in music for me. Part of it is that in my college years in the mid to late 70s into the early 80s, on college radio we just weren’t playing him. I worked at a college radio station, so I was ignorant. I was really dumb! But when I went to the concerts with Dayna (we saw him twice), I think it was a combination of Leonard’s age, just delivering this incredibly beautiful concert where the audience and performers seemed to be at one, and also my own age, where I could much more deeply appreciate what Leonard was singing about. That was, for me, I think, the awakening.

Goldfine: The other thing I think you need to remember is that we’re Americans, so in America, up until Leonard’s five-year, whirlwind, victory lap tour, America didn’t embrace him in the same way the UK and Europe did. So, I don’t think there were a lot of kids growing up in America whose mums had I’m Your Man playing on repeat like you did.

This is something that has always interested me about Cohen. When the topic of the greatest songwriters of all time comes up, people tend to be much quicker to go to names like Bob Dylan or Paul Simon. Why do you think that is?

Geller: I’m not sure that’s true anymore. I think that Leonard in those tours that spanned five years and 379 appearances was introduced to so many people and so many audiences around the world and so many writers about songs that now he seems to be mentioned in the same breath as Dylan. But addressing your point about prior to those tours, I think it’s because he just wasn’t a chart-topper, and it’s easier to pay attention to the chart-toppers, and even Dylan, of course, had massive hits, including in the US. But I think the perception has changed a bit. I know some people were buzzing around the idea of “Why does Dylan get that Nobel prize? It should be Leonard Cohen!”

The idea of exploring Cohen’s life through the prism of Hallelujah is an intriguing one. How did that idea develop between the two of you?

Goldfine: It actually all started over a dinner table conversation with a couple of friends of ours way back in the summer of 2014. David Thompson, who is an amazing British writer about film and a friend of ours, just posed the question of whether we would ever consider doing a whole film about one song. It wasn’t that he named a song, but a few minutes later in that conversation, that image of Leonard, that you saw at the O2 Arena and you definitely see in our movie, stepping into the centre of the stage, getting down on his knees, and beginning to sing Hallelujah during those last five year tours, it just came flooding back into my mind. I turned to Dan and said,”‘I know the song. It’s inextricably linked to the songwriter. It would have to be Leonard Cohen and Hallelujah,” and that kind of set us off on the path. It’s weird how sometimes those dinner table conversations can lead you down a path that’s going to completely absorb you for years and years!

Geller: And we knew from the beginning that the concept would incorporate looking at Leonard through the song, that it wasn’t just a story about a song. Then we found out how good a story it is as far as the song’s genesis, rejection, and then renaissance, but we knew that it was a good way to examine Leonard’s main contradictions that he wrestled with throughout his life, about holiness, brokenness, longing for connection and the impossibility often of achieving that connection with a lover and with the creator. The song is so filled with all of those elements that it more readily permitted itself to be a tool to get inside the mind of Leonard.

Goldfine: And then, of course, the next day after that dinner conversation, we just googled “Leonard Cohen – Hallelujah”, and up came Allan Light’s wonderful book, The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of Hallelujah. That’s where we realised that there was this unbelievable arc of the song, and started tuning into Leonard’s spiritual quest and, as Dan referred to, what contradictions shaped him, what preoccupations drove him throughout his life, and we started thinking that maybe we can do this. So we reached out to Leonard through his then manager, now head of the Cohen estate, Robert Kory, and posed the question to them as to whether Leonard would be willing to give us what Allan Light had called a “tacit blessing”. Alan had received such a blessing to move forward with the book, The Holy or the Broken, and he advised us to approach Leonard much the same way and not ask him for any involvement in the film but just ask for his blessing to move forward with this project, and maybe Sony Music or Sony Publishing would cooperate.

Why do you think Hallelujah was originally rejected and considered a flop?

Geller: The entire album was rejected, so the colossal failure of Columbia Records to recognise Hallelujah was part and parcel of the rejection of the entire album and, arguably, the rejection of Leonard’s entire career, because he lost his recording contract and he was wiped out at that point. So his career was at a standstill although he kept making music. I think the issue was that Columbia Records at that time felt that the audience for Leonard in the US was not going to appreciate that record and so decided not to release it there and to barely back it overseas. Putting it in the context of 1984, Madonna, high production value, Leonard didn’t quite fit in that vein.

Goldfine: I think a lot of it was the time, as Dan said, and I think a lot of it was Walter Yetnikoff, the head of Columbia at the time. Leonard wasn’t one of his guys. Clive Davis had moved on and Walter had taken his place. I think it was this one guy’s decision at the head of this monolithic company to not put that album out, and because it wasn’t coming out in America, there was no supporting tour or radio play, and so the world never really got to know Various Positions, and, thereby, Hallelujah.

Geller: Ultimately they did, of course. When Bob Dylan started playing it live at some concerts where he knew Leonard was in the audience, that’s pretty much a mark of recognition! And then John Cale heard Leonard perform an altered version of the song live at the Beacon Theatre in New York. These are absolutely titanic singer-songwriters who saw something special there.

There’s almost something comical in the part of the film which compiles the song’s usage in TV talent shows which represent quick, cheap success, isn’t there?

Goldfine: I think that speaks to all those elements in the song, not that it’s a cheap, material song! It’s not just the words, it’s that incredible melody which allows you to show off your voice, and it is very comical, you were meant to laugh, at least chuckle, at that sequence! It was just part of the unbelievable trajectory of this song, its ridiculous rejection and how it wended its way into the stratosphere.

Is there any record of Cohen’s response to the song’s use in the film Shrek and the way in which that helped to balloon its popularity?

Geller: This we know specifically from Robert Kory because Robert talked quite a bit to Leonard about these things. Leonard felt that the song no longer belonged to him, that whatever people wanted to do with it in terms of taking it in as their own, he was comfortable with. As he says in the movie in response to a question about that moment in 2009 when Hallelujah by Jeff Buckley, Hallelujah by Alexandra Burke, and Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen were all in the top 40, “a mild sense of revenge entered my heart”. He felt good that this song was finally getting its due, even though in some circumstances, a 12-year-old Indonesian boy singing “all I ever learned from love was how to shoot at somebody who outdrew you” is a little preposterous, but he was glad it was out there, and I’m sure he thought that it’s also a nice way to perhaps get people to listen to some other of his songs.

How did you come into possession of all the archival footage and interviews, and what was it like trawling through it and deciding what to keep in the film?

Goldfine: Archival footage in general, the way we work with it and the way it becomes available to us, it kind of shows up in dribs and drabs, and as you start really delving into a subject and moving forward with a documentary project, some of it finds its way to you, you hear about it, you end up having to beg the person who’s told you about it to actually find it. In the case of the Larry “Ratso” Sloman videotapes, which I think is one of the incredible backbones of the film, Ratso was a journalist and we had had dinner with him many times as we were waiting to clear the rights to the films, so he was comfortable with us, and at the end of our interview with him, he just tossed out there that he thought he might have all of his cassette tapes which contained every time he’d ever spoken with Leonard. It took about a year and a half of bugging Ratso to look in his closets to see if he could find them. So that’s how those materials came to be and, of course, they’re really priceless. A lot of the materials came out of slow trust-building with Robert Kory. Once he saw what we were doing and started to appreciate our approach, he slowly started giving us access to bits and pieces of the archive and that access grew and grew.

Was there anything in the archives that surprised you?

Geller: To see those journals and see page-by-page as he was revising and striking out words that became Hallelujah provided an insight into his creative process that was so privileged. I never imagined we’d be able to see something like that, so that was an utter surprise. It’s not as if just jotted down a lyric and moved on to the next song, you could see his obsession with it. There’s one page as he’s trying to figure it out where he writes, “there ain’t no place to put your Hallelujah”. These beautiful phrases were in there, snippets that aren’t in the song as recorded in its various ways. One thing I loved is that he would use a polaroid camera and take selfies at arm’s length, and those selfies which spanned close to the end of his life are gorgeous compositions and beautiful insights into the man as a visual artist as well as a poet, and a string of those selfies that he took around that ’83/’84 timeframe became the basis from which they chose the cover photo of Various Positions. So that intense closeup of him looking out from the darkness is actually a Leonard Cohen selfie.

Goldfine: Who would have thunk that Leonard Cohen, going back as far as the early 80s would be maybe the first selfie taker!

What are your hopes for the film’s audience? Was it made specifically for fans of Cohen or do you hope that the film will introduce him to a new audience?

Geller: Of course, we always wanted Cohen fans to see the movie, but we made it specifically for a wider audience. We wanted people to get hooked on the idea of Hallelujah, a song that seems so beloved around the world, to bring them into the movie to then understand Leonard Cohen, the man, the secret of the artist. It’s like the Hitchcock MacGuffin. That aspect is something that we’ve seen, touring the world with the movie, really connecting with people. It may not be particularly devotees of Leonard Cohen, but they come to the movie and have a real emotional experience, so that is the great reward, and we’re thrilled that it is playing in theatres around the world.

Goldfine: I guess I would say both/and to your question. I love it when we talk to someone who has seen the film, like yourself, and talks about their experience of seeing him live during that tour. It brought back a rush of memories because those concerts were really one of a kind. I also love when someone just stumbles into the theatre because they’re intrigued. They walk out of the theatre wanting to listen to Leonard’s entire catalogue. That makes me really happy because, of course, in the film, although it’s primarily looking at Leonard through the prism of Hallelujah, we slyly stuck in another 22 Leonard Cohen songs.

Matthew McMillan

Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song is released in select cinemas on 16th September 2022.

Watch the trailer for Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS