William Kentridge at the Royal Academy

Born in 1955, much of the South African artist William Kentridge’s life has been spent living under apartheid. The son of two eminent human rights lawyers, Sir Sydney and Felicia Kentridge, who defended the likes of Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the artist’s practice has for the last four decades brought into sharp focus the brutality and moral repugnancy of that period of racial segregation. Since South Africa’s transition into a democracy in 1994, the social issues besetting Kentridge’s homeland have continued to shape his creativity. Now the Royal Academy is unleashing the biggest show of the Johannesburg-based artist’s work ever to be held in the UK, featuring his drawings, sculpture, animations and filmed performances.

Right from the outset, one finds early examples of his fluent draughtsmanship in the form of monumental charcoal drawings from the 1980s. The Conservationist’s Ball, triptych (1985), a societal satire, recalls the work of the German Expressionist, Max Beckmann. The elegantly dressed white elite – Kentridge depicts himself as a reluctant observer – dance and mingle as wild animals wander amongst them. They are stripping Africa of its wild animals and using it as a form of entertainment – game watching. In the third part of the triptych, a hyena, representative of brutal state enforcers, surveys an abandoned city left in an apocalyptic state, from a car roof, absurdly wearing roller skates.

Over the last 33 years, Kentridge has produced a series of short black-and-white animated films, deploying a technique of drawing with charcoal, then erasing and drawing on the same piece of paper. Five of the 11 films in his series Drawings for Projection are to be found in one room here. The first, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris is an eight-minute work that introduces the viewer to the fictional characters Soho Eckstein, an archetypal mining plutocrat and Kentridge’s alter-ego, a struggling artist named Felix Teitelbaum. Set against the backdrop of the harsh realities of the mining industry in Johannesburg, the film has at its core the love triangle between Eckstein, his wife and Teitlebaum. In City Deep (2020), one finds the mineshafts abandoned and unlicensed workers trying to bang out the last traces of gold. Eckstein appears wandering through the Johannesburg Art Gallery with portraits of miners coming to life as the museum’s walls fall apart to be transformed into the city’s pitted landscape. These amassed films hold you captivated: a whirl of sound and animated charcoal.

In another gallery, the artist has drawn imagery directly onto the wall to accompany his 1997 film, Ubu Tells the Truth. One finds recurrent visual motifs, such as a film camera and a rhinoceros. Kentridge’s absurdist humour is very much in evidence in his Drawing Lessons video later in the exhibition, where he appears in dialogue with himself, both in the guise of artist and overbearing interviewer questioning the relevancy of his work. The visitor sees recent giant flowers, painted in ink on pages ripped from dictionaries and encyclopaedias, followed by a tree series rendered vastly in Indian ink. Surrounded by loaded pasted phrases, the latter is rooted in a Johannesburg landscape.

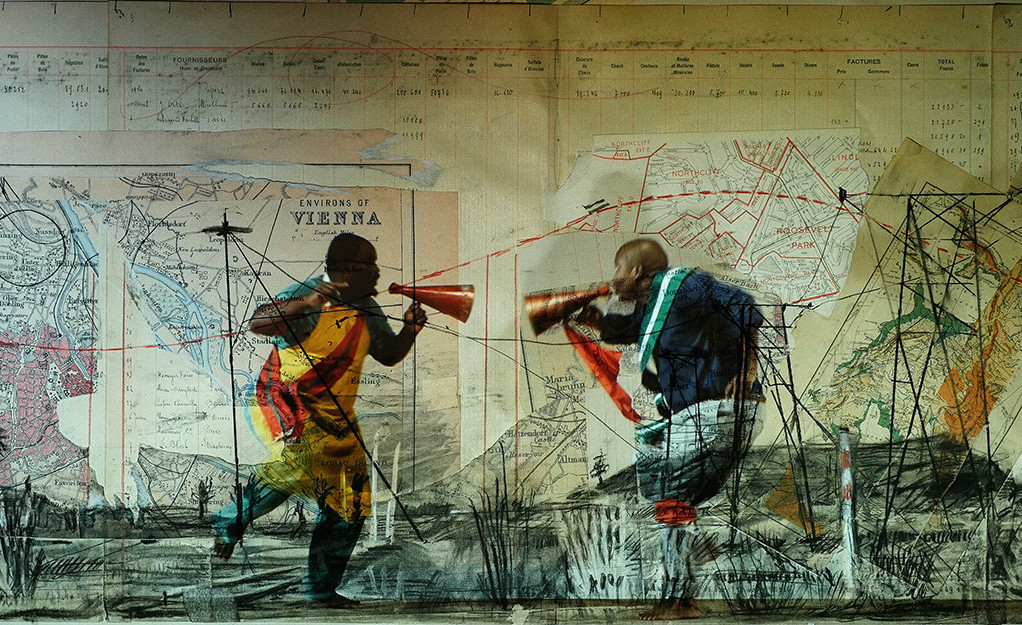

Kentridge has frequently brought into focus the effects of colonialism in Africa. In a series of charcoal and pastel drawings, he draws directly from old photographs, exemplified by Victoria Falls (Colonial Landscape) (1996). The landscapes were being viewed by white Europeans as beautiful wildernesses without people. Elsewhere in the exhibition, one comes across large mohair tapestries of migrants superimposed on top of maps to conjure the legacy of colonialism.

This colonial theme continues with Kentridge’s Black Box/Chamber Noir (2005), a mechanical theatre featuring automated puppets, changing backgrounds and projected film. The work considers the genocide perpetrated by German colonial troops in Namibia in 1908 where they brutally suppressed the Herero and Nama people. The playful nature of the production is at odds with that of the horrific subject matter.

A three-screen film, Notes Towards a Model Opera (2015) takes as its prompt the operas promoted by Mao Zedong’s wife, Jiang Qing, during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. A black ballerina dances with a red flag, a rifle slung over her shoulder. Kentridge has commented on how speed is a function of the piece with images flying past the viewer in disorientating fashion, echoing the information overload of modern life.

A compelling exhibition reaches its finale with the artist’s film Sibyl focused on his chamber opera, Waiting for the Sibyl (2019). It tells the tale of the entrance to the Underworld in Virgil’s The Aeneid where the curious would leave questions related to their fate written on leaves for Sibyl, the oracle, to answer. She too would reply on leaves but the answers would become mired in confusion, dispersed by the wind. The very narrative brings to mind the artist’s professed dislike of certainty, a state of mind he associates with authoritarian dystopias. Kentridge uses a combination of animation and filmed shadow-play, with actors wearing spectacular costumes. People move between papers falling as if swept up by a gale. Accompanying music by the composer Nhlanhla Mahlangu provides added emotional resonance. It is a dramatic end to a consistently stimulating, impressively multi-disciplinary retrospective.

James White

Image: Royal Adademy

William Kentridge is at the Royal Academy from 24th September until 11th December 2022. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS