The Lost King

Stephen Frears has never shied away from the regal. The Lost King immediately follows 2017’s Victoria and Abdul in his oeuvre, while 2006’s The Queen saw him pretty much cut to the chase. And, in case you hadn’t had your fill of the pomp and ceremony of royal interment as of late, Frears’s timely comedy-drama has you covered.

The Lost King is the first film to sink its teeth into the extraordinary excavation of the remains of King Richard III, and the tireless passion, or fruitful madness, of amateur historian, Philipa Langley (Sally Hawkins), without whom the ultimate Plantagenet King of England’s bones would still be languishing under the unremarkable council car park in Leicester.

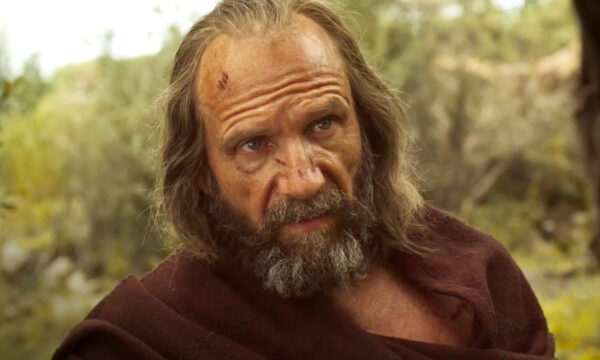

Langley, a 45-year-old middle-class professional living in Edinburgh with her two sons with the support of her estranged husband, John (Steve Coogan), has just been shunned for a promotion, the reason for which she attributes to her age and her persistent Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. After attending a local production of William Shakespeare’s Richard III, Langley becomes fixated on the pitiful figure that is Shakespeare’s deformed, frightening King. She appears enchanted as Richard (Harry Lloyd) laments on his physicality as the source of his evil nature, identifying with his sorrow rather than aligning with Shakespeare’s maligning intent.

As a result of this newfound infatuation, fused with her chronic condition, Langley begins experiencing hallucinations of the King stalking her at her workplace and relaxing on a bench within view of her bedroom window. Becoming driven by a compulsion to correct what she sees as a harsh historical assessment of Richard III rooted in Tudor propaganda, Langley joins the Edinburgh branch of the Richard III society, a contingent of six offbeat characters who share a similar, borderline maniacal obsession with the King. It is a borderline mania that the film does not shy away from, and factors largely into what makes Langley such a fascinating character study.

To everyone around her, she is losing her wits. As she descends into the depths of what appears to be dead-end research, she barely shows up for work and allows her obsession to consume her. You begin to get the sense that, had her research not yielded results, institutionalisation may have beckoned. Hawkins expertly balances on the pivot between a steadfast disposition and an imminent breakdown, capturing the jittery passion of Langley down to a tee. The scenes between Langley and her apparitions of the King also function neatly. While these quaint hallucinations could easily have sent the movie hurtling into imbalance, they imbue it with an offbeat allure, one that reflects the madness of its protagonist.

Despite the feature’s tone of Edinburgian charm, centred around a family unit which is imperfect but good-natured in its efforts, the film has been in the eye of an academic storm, with a pervading sense that the film’s script, co-penned by Coogan, paints the academic institutions involved in the research, funding and planning of the excavation alongside Langley as stumbling blocks rather than stepping stones in the process. There is certainly a hint of cartoonish villainy on the part of some academic figures, with Richard Taylor, then deputy registrar of Leicester University, and played with smug relish by Lee Ingleby, being portrayed with particular chauvinistic arrogance, a disposition which Taylor has refuted.

However true the specifics of these dynamics may or may not be, the film does raise a pressing concern about universities as profit-driven businesses, as opposed to benevolent bastions of knowledge, a point of creeping concern in the wake of Sheffield Hallam University’s decision to axe its English Literature course. There has also been a challenge to the film’s alleged overestimation of Langley’s financial contribution to the project, although all parties acknowledge that, without Langley’s drive, this fairytale would still be buried under the gravel.

Within its own framework, however, the film is a treat. Spearheaded by Hawkins’s performance, and guided by the dexterity of Frears’s craft, the The Lost King not only constructs an intriguing and understatedly bold character study but crystallises the latest historical evaluation of Richard III’s reign.

Matthew McMillan

The Lost King is released nationwide on 7th October 2022.

Watch the trailer for The Lost King here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS