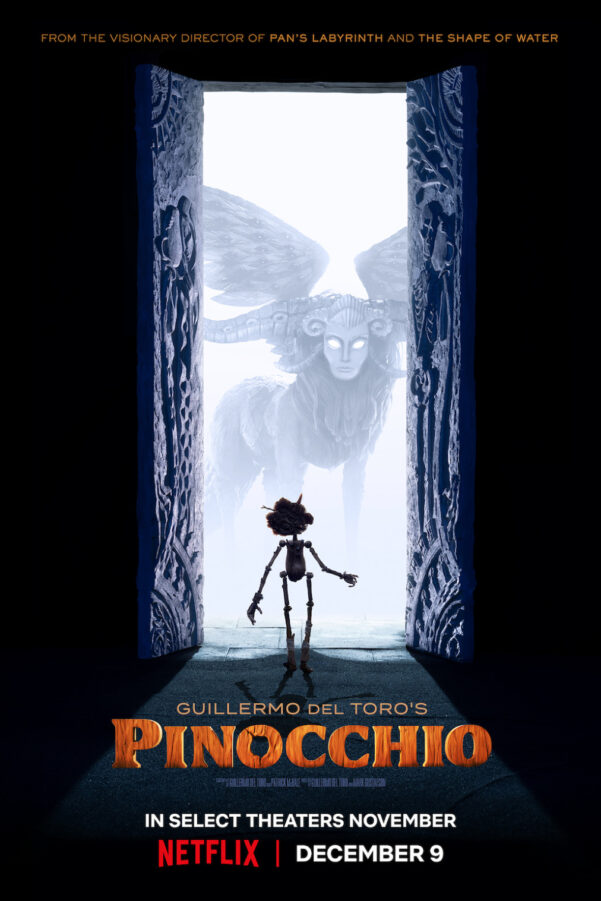

“I was very interested in making a story in which everybody behaves like a puppet except the puppet”: Q&A with director Guillermo del Toro on Pinocchio at London Film Festival 2022

In the pampered, ornamental grace of London’s Soho House, a cluster of reporters eagerly awaits the screening of a 40-minute clip of the latest screen adaptation of Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio. All in attendance have seen riffs on the story which tap into a feather-light tone, a “Disneyfication” of Carlo Collodi’s source material which stretches back to the nostalgic hues of the 1940 classic. But all were also acutely aware that the auteur behind the 40-minute tease is not one for feathery sentimentality. Guillermo del Toro’s filmography has, more often than not, relished the fusion of the political and the gothic. Consequently, from the perspective afforded by hindsight, placing Pinocchio in an Italy asphyxiating in the suffocating grip of fascism is a logical direction for del Toro to take the story, a direction which helps bring the wickedness of Collodi’s novel closer to the fore than audiences may be used to, or even comfortable with, flammable feet and all.

Del Toro suggested that this was a significant factor in the prolonged realisation of the project: “The journey started actively about a decade and a half ago, partnering with Gris Grimly, Matthew Robbins and Patrick McHale, who wrote the screenplay. The journey took a long time mainly because the things we wanted to try were different. We didn’t want to make a slick piece of hip, accessible, shopping mall-friendly animation experience. We wanted to push something that felt handmade – painstakingly so – by humans, returning the control of the animation to the animators whom we addressed as actors.”

Del Toro speaks of a kind of animation orthodoxy (to invoke unfortunately Trussian language) as “pre-determined poses that everybody has codified into a core language that is almost emojis”, something that he and his team actively sought to avoid. Instead, the aim was to “provoke from these puppets stumbles, itchings, sweat, joints that hurt, and make them transmit to the audience what they feel”. He again draws attention to the word “handmade”, suggesting that the Geppetto-esque craft of the process is what imbues the film with its dark heart.

After the footage screening, del Toro returned to take questions, and the puppets of Pinocchio and Geppetto were passed around for audience members to inspect. “When you get a turn to hold it, try to move it,” he suggested. “Because that’s what we had to do 24 times for a second of footage to be achieved.”

“Stop motion has been a lost art since it started,” he wryly cracks in response to a question about the animation technique. “It is the most exhausting, demanding form of animation. It’s only done by a group of completely and utterly strange people that sustain it time and time again against reason…Over the last 20 years, it has moved to a point, technically and philosophically, where it was almost indistinguishable from CG animation. We wanted the immediacy of a set that you know was carved, sculpted, aged in a way that was manually done.”

On the decision to orient the story in the midst of a fascistic climate, del Toro spoke about the choice as a continuation of themes that had been explored in some of his previous works. “This movie, for me, is of a piece with Pan’s Labyrinth and The Devil’s Backbone. These three movies are about childhood against war and violence. I think the movie is about fatherhood. Fascism seems to be about a concern with a father figure of a different kind which unifies thought. So it’s both a background and a thematic choice.”

“An interesting challenge for me was to make a Pinocchio which celebrates disobedience rather than obedience…I didn’t want Pinocchio to learn change. I wanted Pinocchio to change everyone around him…I was very interested in making a story in which everybody behaves like a puppet except the puppet.” Gris Grimly’s illustrations were commented on as a touchstone for a more unruly aesthetic for the wooden boy: “I knew this needed to be a movie with this design, which is more elemental, more savage, more primordial, a Pinocchio carved in a drunken night as opposed to being beautifully crafted.”

A rebellious streak seems to be baked into the artistic disposition of Guillermo del Toro: never one for compromise, always one for challenging himself and his audience. “I’ve been a contrarian for 30 years, and I intend to continue,” he quips with cheeky defiance. Long may that defiance continue.

Matthew McMillan

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is available on Netflix from 9th December 2022 and will be released in cinemas at a later date.

Read more reviews and interviews from our London Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the festival visit the official BFI website here.

Watch the trailer for Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS