“Being a playwright is the best job in the world in my opinion”: Writer Nathan Ellis on Super High Resolution

Writer Nathan Ellis is a member of the BBC Drama Room and has several television projects in development. On stage he is known for his debut No One Is Coming to Save You as well as the critically acclaimed work.txt – a play without actors. Now under the direction of Blanche McIntyre, Soho Theatre will present the world premiere of Super High Resolution. The play, which focuses on the NHS, was shortlisted for the prestigious Verity Bargate Award, the judging panel of which included Phoebe Waller-Bridge. Ellis took time out to speak with us about his latest theatrical offering.

Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to The Upcoming about your new play, Super High Resolution. What can you tell us about the play and what can audiences expect?

Super High Resolution is a play about an A&E doctor called Anna. It’s about the pressures placed on them and the ways that impacts their personal relationships. I think of it as a comedy, but it goes to some pretty dark places.

How much research did you conduct, or did you draw on personal experience when tackling the project?

My sister is a doctor, and while I was writing the play, I was living with her and she was thinking about quitting medicine. She’d had enough and she was finding she was having her empathy worn down, through stress and exhaustion. I then I read a lot about trauma, moral injury and life as a doctor, but the process of digging into the play was really about trying to explore how to deal with difficult emotions in a healthy way.

Tell us about your writing process. Do you approach each script in the same way?

I’m a big planner – I spent about nine months thinking and planning the play, and didn’t write anything, and then it was a very, very quick writing process. The planning takes the form both of thinking through the plot and also trying to make strong decisions in terms of form – something I’m fairly obsessed with. Form is the way the play gets put together that isn’t contained in the words – its theatrical gesture – and it’s always one of the first things I get excited about in a play. In SHR, the gesture is the actor playing Anna never being able to leave the stage, which is about trying to mirror the non-stop exhaustion of being an A&E doctor in a theatrical space over time. Dragging form and content into an interesting relationship with each other feels like a common approach, but different plays demand different things in terms of process.

Are you the type of writer who carries a pen and pad around waiting for inspiration to strike, or do you actively go looking for stories?

I do carry a notepad around. I think that’s a writer’s prerogative! But really all my best inspiration happens when I’m walking around and reading. I also find a lot of inspiration in seeing other people’s work – it’s incredibly helpful to spend time thinking about what I like and don’t like in other people’s art to try to hone my own craft. I find it particularly helpful to see theatre I don’t like very much; I’ve had some of my most exciting ideas while incredibly bored in an audience. Hopefully some writers will come and hate my play and write something brilliant as a result!

What is your earliest memory of theatre?

Putting on shows with my sisters for my parents, normally based around the Spice Girls. I was very bad at the choreography but made a very enthusiastic Baby. And I went to see Wicked when I was about ten, and that blew my tiny mind. Now my tastes are much more esoteric.

When did writing itself come into your life? And when did you realise it was something you wanted to do for a living?

I studied English at university and always liked writing, but I genuinely didn’t realise that new writing was a thing people did until after I graduated – which makes me sound a bit thick, but it’s true. I think you have a different relationship with culture growing up in a city, maybe. It wasn’t until I moved to London and started going to new writing nights and seeing that the people writing the not-very-good plays were my age that I thought, “Hey, I too could write some not-very-good plays.” So that was the start of it really. I did a bit of it and it was the most thrilling thing I had ever done, seeing actors performing my words. I got absolutely hooked.

Have you ever experienced writer’s block or struggled to find inspiration?

No. I count myself very lucky. I definitely struggle to know if things are going in the right direction – improving – when I’m writing something, I find I can get very lost about halfway through, and run out of confidence, but then I remind myself that people have proper jobs and I’m just tapping away on a laptop, and that seems to help with any grandiose thoughts that what I’m doing is in any way risky.

Are there any writers who influence or inspire you at all? Have any particular plays stood out for you in recent years?

Loads. In terms of contemporary writers, I’m very into Alice Birch, Rory Mullarkey, Miranda July, Chris Thorpe… Anatomy of a Suicide is obviously the best play of the century – I saw it three times. My favourite show is Dionysos Stadt by a director called Christopher Rueping, I love his work. I saw Civilisation by Jaz Woodcock-Stewart and Morgan Runacre over the summer. That really did me in, it felt absolutely masterful.

Your previous work, No One Is Coming to Save You and work.txt garnered great praise. Does this put pressure on you as a writer to deliver the goods again? How much attention do you pay to reviews?

“Great praise” might be an overstatement, but, yes, it was nice some people liked them. I am really proud of the plays and particularly the ways they got made. It helps knowing the integrity of the process, the acts of extraordinarily talented people in making the thing happen; that’s the stuff that sticks in my mind, not really what reviewers said about them. I feel the same about SHR: the people working on it absolutely deserve praise, but if the reviews aren’t great, that won’t matter hugely. It’s been such a privilege to see their work come together.

Acting on stage can provide an immediate response to your work as the audience applaud – writing is a far more isolated endeavour. Do you find solace in that, or do you yearn for collaboration, either during the writing process or when it gets to the rehearsal room?

Writing for theatre isn’t actually so solitary. I spend a lot of time on my own, but the actual writing time is quite limited – you could get up tomorrow and retype every word I’ve ever written and you would be done by teatime. It’s a complete joy working out solutions to problems on your own and imagining how what you’re doing might end up onstage, but you always have in your mind that eventually it will be in a room with other people – that’s why being a playwright is the best job in the world in my opinion.

Once a play is in the director’s hands, how much creative input do you generally get during the rehearsal process? Is it hard to let go of the baby, or do you fully embrace other creatives taking the reins or bringing their ideas to the table?

So far I have only worked with brilliant directors, and that helps. I made a decision with SHR to just trust the director entirely, and it has, fortunately, paid off. I spent the first week making small tweaks to the text to fit the brilliant actors, and answering questions when they came up and I could be helpful, but my creative interventions in rehearsal are very limited. I’m amazed by what the other creatives have come up with, I don’t have better answers than them.

How have you found working with director Blanche McIntyre?

She’s amazing; kind and funny and fiercely intelligent. She’s far too humble to acknowledge it, but she’s really an incredible director, in a quiet, unfussy, yet intensely detailed way. It’s magic to watch her work – she has no critical words in her vocabulary, and seems to direct by an instinct of compassion. I feel so lucky.

You’re currently developing some projects for TV and you are part of the BBC Drama Room. How differently do you approach a screenplay to a stage play?

Both types of writing are amazingly difficult to get right, but in different ways. Screenplays respond much better to fast plots and to visual language. Very basically, scenes are much longer in plays, and characters have to return more often, so they all need to be intensely distilled. But it’s also true that the basics of good dramatic writing carry across into screenwriting.

There are so many budding writers but it’s an incredibly competitive field and one that’s notoriously hard to break into. What advice would you give to someone hoping to write a script and get it out there?

Read a lot of plays – as many as possible – and think about them. The drama department in Foyles on Charing Cross Road is really good. And you absolutely have to buy the play; you definitely can’t just read them in the cafe on the top floor in about an hour and then put them back on the shelf. That is definitely wrong and bad and I have never done that even once and absolutely would never advise that.

Do you think theatre is in a good place currently? What, if anything, do you think is missing from the art form?

No, in short. It’s criminally underfunded and it’s pushing the wrong people out. The people working in theatre are incredible – the talent and passion is extraordinary – but the sums don’t add up, and we’re going to end up in a place where it’s just famous people doing revivals of plays by already successful playwrights, and then the politicians will turn around and say that theatre isn’t reflecting British culture. It’s depressing.

What’s next for you and are there any upcoming projects we can we look forward to?

work.txt is going on tour internationally next year, Super High Resolution is being produced in German in Kassel in February. Alongside the screenwriting stuff, I’m also in the R&D phase of a new experimental play I am directing about surveillance capitalism and I am writing a new play about hiking.

Finally, if you had to sell Super High Resolution to us in just a sentence or two, what would you say?

A play about the impacts of caring for other people. With several good jokes.

Jonathan Marshall

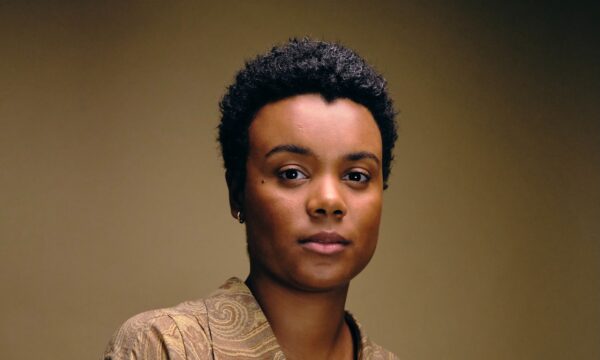

Photo: Helen Murray

Super High Resolution is at Soho Theatre from 27th October to 3rd December 2022. For further information or to book visit the theatre’s website here.

Watch a trailer about the production here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS