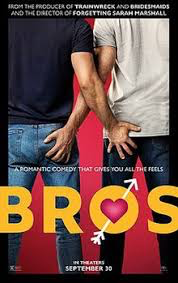

Bros

Mainstream cinema has always been shy about queerness. LGBTQ+ stories have, more often than not, been told and performed by straight people with the appeasement of straight audiences a creative pre-requisite. Nicholas Stoller’s Bros, curiously the first gay romcom to be developed by a major studio, is acutely cognisant of this cinematic context, consciously orienting itself within its influence. When we meet Bobby Lieber (Billy Eichner), we find him in full flow on his podcast, The Eleventh Brick at Stonewall, relaying his happiness as a single man whose sex life consists of mostly fleeting encounters with men met on dating apps. In the same stream of consciousness, Bobby tells his listeners about the rejection of a lucrative offer he received to write the screenplay for a gay romantic comedy. “Love is love,” says the producer during a meeting, as a kind of guiding principle on which the story will hang. But Bobby, singular in his views about the lived experience of being a gay man, is adamant that love is not simply “love”. In his mind, gay love is something unique from its heterosexual counterpart, and the gay community are often a distinctly frustrating community to be a part of, especially if you’re not one of the “dumb ones”.

Bros seems to fit Bobby’s expectations of the shape such a film should take. It is, therefore, a production that is, to some extent, commenting on itself and its own place in the history of queer cinema. As a consequence, it borders on the meta, a self-referential flair that gives the film more intellectual intrigue than it otherwise ought to possess, although it does occasionally threaten to interfere with the motion of the storytelling. The casting of Luke Macfarlane as Aaron Shephard, Bobby’s romantic interest whose day job of managing wills has consumed his childhood dreams of chocolatiering, is an astute piece of casting that further layers the film’s self-awareness. Having appeared in a number of Hallmark movies, the tokenism of which is satirised very directly in Bros (it exists in the world of the film as “Hallheart”), Macfarlane’s casting has genre implications in of itself. His performance gives the playful mischief of the casting justification, however, as he introduces himself to a mainstream audience as a nuanced performer whose restraint balances out the scene-stealing exuberance of Bobby.

In spite of its satirical intention, with the referential use of the Hallmark end of the romcom spectrum, Bros occasionally adopts some its inherent flaws as contrivances, especially as it sings its emotive high note; it’s eye-rolling at worst, but to be expected – maybe even forgiven – in a Apatow-produced genre entry. Even when it falls into its genre’s traps, it does so with a pert nudge and a wink.

After accepting the decreasingly coveted award of Best Cis Male Gay Man at an LGBTQ+ awards ceremony, Bobby reveals his participation in a committee overseeing a new LGBTQ+ history museum. He pours his bold ideas into the cauldron, including a commemoration of Abraham Lincoln, about whom he is sure there is enough historical evidence to confirm that he was America’s first gay president, but who others on the committee are sure was just “probably bi”. Aaron, however, views his sexuality through a less politicised lens, and feels challenged by Bobby’s fervency – so much so that, when his parents come to visit, Aaron asks Bobby to “tone it down”.

While very entirely different propositions, it is a tension not dissimilar from the one that marrs the central relationship of Georgia Oakley’s debut feature, Blue Jean. Far from the heft and subtlety of that film, Bros is an agile romp full of acrobatic ideas. It falls short of the great romcoms (When Harry Met Sally has been cited as something of a companion piece, and is directly referenced in a meta indulgence), but its frankness and zeal see it stand on its own two feet.

Matthew McMillan

Bros is released nationwide on 28th October 2022.

Watch the trailer for Bros here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS