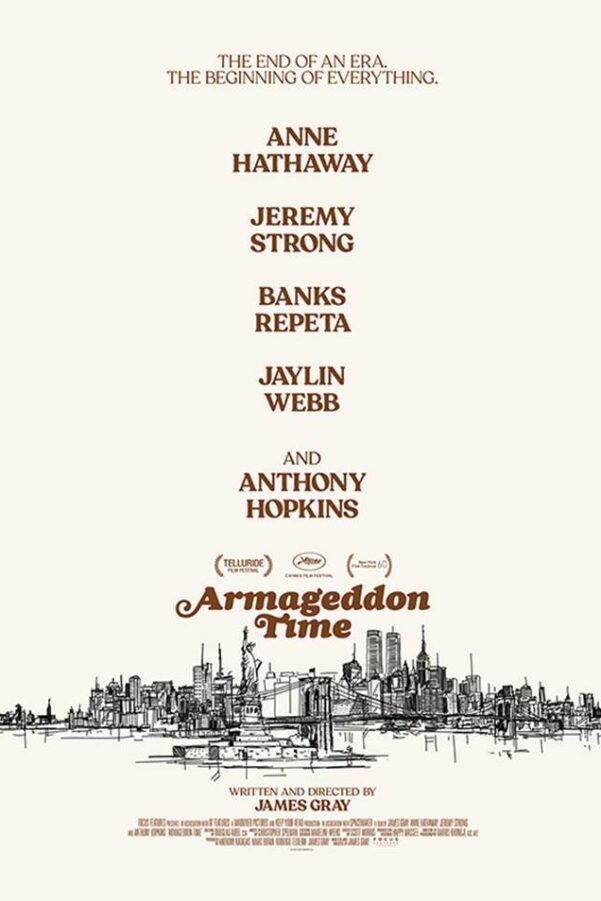

“It’s not always so easy to know who the bad guy is, and that’s okay”: James Gray on Armageddon Time and revisiting his childhood on screen

Armageddon Time is the coming-of-age, family drama from renowned filmmaker James Gray, and undoubtedly his most autobiographical film yet. In some respects, one can draw a line between some of the anxieties and themes that emerge from his other movies (whether set in the Amazon, like The Lost City of Z, or up in space in Ad Astra, starring Brad Pitt) that are perhaps rooted in the events that unfold in this 1980s New York-set film.

The story follows Paul (Michael Banks Repeta), a 12-year-old boy based on Gray himself, trying to navigate life in a Jewish family in the context of a racially divided city, unrest stoked by Ronald Reagan, who was running for office. When he strikes up a friendship with a Black boy from his class in public school in Queens, Johnny (Jaylin Webb), these divisions start to show themselves in the different ways the two boys are treated – by society and in the eyes of the law – when they get up to no good. Paul’s parents believe the only solution is to send him to a posh, conservative private school, where the N-word is freely thrown around, leading him to be torn about the friend he leaves behind.

It’s a bold story that sets itself apart in contemporary cinema by resisting the temptation to make heroes and villains of the characters involved. Even Paul’s parents, played impressively by (in fairly left-field casting) Anne Hathaway and Jeremy Strong, in many ways aren’t without their flaws in terms of their views on class and prejudice, his father, in particular, using physical abuse as a form of punishment, but their representation still holds a sense of love and affection. Paul’s grandfather, an always reliably good Anthony Hopkins, is Paul’s emotional saviour, and their exchanges offer the most touching moments of the story, yet, equally, he doesn’t always give sound advice. Ultimately, Paul himself makes very questionable decisions.

But the film is neither asking for judgement nor redemption; more, it seems the director is unearthing a buried truth about his past, a story and an aspect of himself he has been circling his whole career, that he has finally found the courage, maturity or the right mindset to share with the world. The Upcoming had the pleasure of chatting with Gray ahead of the release about the nuances and ambiguities in the film that seem to fly in the face of pervasive modern-day notions of morality and his journey to making it.

An easy question first: could you begin with a brief introduction to Armageddon Time? What can audiences expect when they watch it?

An honest look at what it means to be 12. That’s about the best way I can put it.

It seems there are lots of themes here that you have explored in your other film, but you’ve perhaps taken a circuitous route to come back home to your own story and childhood. Would you say this is your most personal film to date?

I’ve always tried to make films – whatever the case is, even if they take place in Amazonia, or space or whatever – I’ve certainly tried to make them as personal as I can. But your point is well taken. How autobiographical is it? Well, it’s extremely autobiographical, obviously. I really tried to make up nothing. There are some [differences] – the timeframe is much shorter: in the movie, it’s about three months, in real life, it’s probably about a year and two months, something like that. And there is some what we call “compositing – some things that happened to my brother that I put into my story, and some things like that I had two friends, and I made them into one friend – you know what I mean? Things like that. Because you can’t make a movie that’s like ten hours long unless you want to do it for TV. And I think two hours of me is about enough. But, having said that, it’s quite close to my recollection of things. It’s funny, I showed the film to my brother. He went to see it at the New York Film Festival. I was sort of gutless and didn’t want to show it to him for a while, but he finally saw it, and he thought it was extremely accurate to his recollection. So that meant something, because his memory is pretty damn good.

Why did now feel like the right moment to go back to New York and make this film? Was it what you expected? We read about how much the city had changed, so you had to actually recreate an old New York, almost like a period drama?

Well, I’ve joked about this in other places as sort of like how lower back pain reminded me that I was old – you start to realise that you may have more days behind you than you do ahead, and you start to look back over your own life. And sometimes you love what you see, and sometimes you don’t. And I liked the challenge of putting forth an image of myself that really is not altogether flattering all the time. I felt that that was a challenge that I wanted to meet, that I was anxious to express: “Here I am, warts and all”, and it’s sometimes not so pretty. But also the times – I think 1980 plays a really pivotal role in the history of the United States, and, by extension, the world. And the roots of what we see now – in the rise in autocracy and in this kind of revanchism, like you see Putin going and invading Ukraine, and so forth – a lot of it has its roots back then, because, back then, what you had was a rather simple dichotomy: you had the United States and the Soviet Union locked in a kind of Cold War battle of wills where they used to talk about Armageddon, the prospect of Armageddon, all the time. And the Soviet Union started to fray. And when it finally fell apart, the market became God, and the world really changed. So I felt that it was really the end of the 60s and 70s optimism – it died beginning in 1980. And I was anxious to put my own childhood failings against that backdrop. It just was timing.

There’s so much complexity and moral ambiguity in the film – it’s perhaps not placing judgement, but more trying to present your past in a true and authentic way, and letting the chips fall where they may. Even the representation of your parents: though you’re showing their flaws, there’s also a lot of affection there. Equally, Paul is kind of obnoxious, but he’s also a child trying to navigate being in a Jewish family, racial inequality, trying to assimilate into a White world and understand the exchange that has to be made in order to do that. What themes do you think are laid bare?

Well, first of all, I’m thrilled by what you just said because, obviously, that’s the intention of the movie. And I would embrace the term “moral ambiguity” because one of the things I’ve noticed – and we’ve discussed now how old I am – but one of the things I’ve noticed, as I get older, is I consider the world a much better place in some ways. My children, for example, are extremely aware of LGBTQ+ more than I ever was at age 12, or issues of the ideas of privilege and racism in a way that I was clueless about. But my children are also very prone to moralise, and to not understand that the world is a very complex place – that you can be both the oppressor and the oppressed at the same time, that you can have the best of intentions and still screw up royally. And my children are unbelievably poorly educated, much as I love them, on issues regarding capitalism, and its role in things like racism. So I was trying to make a film showing the layers that are involved, and not to provide an answer, or the kid that’s the stand-in for me winning the day and doing the right thing – no, no, no, no. If anything, the child is left with a more complex and unanswerable series of questions at the end than he has at the beginning, because I feel like that’s the passage we go through in life: we get kind of dumber and dumber as we get older, because we realise that it’s almost like these things are systemic and marbleised and not so easily digestible in slogans or solutions with one line. And this is something I’ve noticed that’s very different since 2014, around there. Perhaps it’s a product of social media, but this idea that we’re pointing fingers and saying, “We’re better than that person”. So, if I said to my father in 1980, who was a boiler repair man, if I said, “Dad, you are the beneficiary of privilege”, my father would have told me I was insane. And he would have gotten very angry. But, if I talked him through it, and I spent the time to try and explain it to him, at the end, he might kind of go – and, in fact, I’m sure he would – he would say, “Oh, I see what you’re saying”. And so I feel like today the attitude is, “You’re the beneficiary of privilege”, “No, I’m not”, “Okay, well, then screw off”. No, no. What I was trying to do was use… dare I use the dirty word “art” to unpack all the layers that are involved.

Coming to your brilliant casting decisions: these actors are perhaps not the most likely people to see in those roles, particularly Anne Hathaway, but also Jeremy Strong – we’ve all been watching Succession and this is a very different role for him – and Anthony Hopkins, Jessica Chastain and your young actors. How did you choose these people and work with them? When something’s so close to one’s heart and so personal, there’s must be extra pressure to really impart your truth to the actors.

Yeah, I was very resistant to casting people that would fit into a stereotype of New York Jewish American life, because that wasn’t really how my parents and grandparents were. It wasn’t that “Hello, my name is Moshe. I’m a typical salesman”, which you see in films, and which, by the way, those people did and do exist, but it’s become a rather brutal stereotype. My grandfather had come in through Southampton, and was a very proper man and very well dressed and my parents looked, talked and acted exactly like Jeremy and Anne in the movie. Who I was trying to cast the film, as I saw, were actors sort of matched up with my parent’s souls, more than the idea of being able to do some kind of, “I’m a New Yorker and I’m talking like this”. Because I, as you know, have an accent. Of course, I’m from New York, but I don’t actually speak like that. So, for me, it became about being emotionally true. And what was very weird – although I didn’t want them doing imitations of my parents, I wanted them to bring themselves to the role – was they then wound up somehow, even with as little as I told them, playing my parents exactly. My brother felt that they were basically exactly like my parents, so something happened there.

What do you hope people will take away from watching the film? And do you feel like you’ve finally scratched an itch now you’ve made it? Where you might go next?

I have no idea where I’m going to go next – I’m still talking to you about this one, and I only finished it about six weeks ago. We took a rough cut with a three-day temporary mix to Cannes, so I’ve been working on this movie until late August, or early September, and I’m quite tired. My batteries are not yet creatively recharged. So I have absolutely no idea whether my itch is scratched or what I’m going to do next or anything. So there’s that. But also, what do I hope people take away from the picture? I hope they see the world and that there are many layers involved, and then it’s not always so easy to know who the bad guy is. And that’s okay. Because the way to unpack some of these problems is to stop pointing fingers and blaming, but to try to understand.

Thank you so much for sharing all that with us.

You’re welcome.

Sarah Bradbury

Photo: Ambra Vernuccio

Armageddon Time is released nationwide on 18th November 2022. Read our review here.

Watch the trailer for Armageddon Time here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS