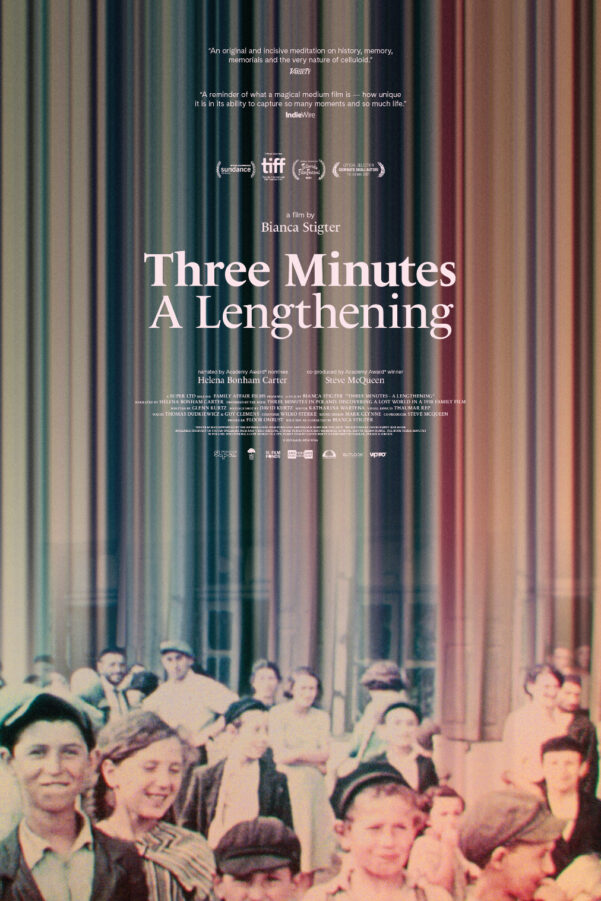

Three Minutes: A Lengthening

While Three Minutes: A Lengthening is ostensibly an academic contemplation on the metaphysical nature of film, to describe it as such would be a disservice to a documentary with a ghostly, aching heart. While certainly of academic and historical import, Bianca Stigter’s haunting revivification of souls lost to history is a groundbreaking experience that is as mournful as it is informative.

The titular three minutes refers to three minutes of amateur footage shot on 16mm film in 1938. Sketching a brief but illuminating portrait of the Jewish neighbourhood of Nasielsk, Poland, the footage is a distillation of a world departed: a world of families, grocery stores, social hierarchies and children, ecstatic and dumbfounded at the presence of this strange new technology that had already begun to alter the essence of the human experience. The film was discovered at the brink of irreversible disrepair in 2009 by Glenn Kurtz, whose grandfather, David, a first-generation immigrant to the United States from Nasielsk, took the footage while on his “grand tour” of Europe. Upon its discovery, Glenn began work to restore the footage and set about trying to identify the nameless faces and their collective milieu, first establishing the town’s location, and then attempting to piece together the fragmented clues, which, when assembled, paint a broader, more realised picture of the town’s pre-war reality. This initial research laid the groundwork for a book titled Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film.

Stigter’s film not only contributes further to Kurtz’s existing research but adds a beautiful, meditative layer of meta-documentation to it, ruminating on the physical strip of film as a preserver of historical information. Raking through the information projected by the footage imparts such knowledge to us as the time of day the footage was taken, and the public event that may have encouraged the feverish, carefree festivities immortalised by Kurtz’s handheld camera, as well as some of the small, refined details that collectively constituted objective reality for the population of Nasielsk. Stigter makes the choice to dispense with talking heads, opting for interviews and narration that take place over the rolling, restored three minutes. It is almost as cinematic as any narrative feature, as Stigter is just as concerned with immersive world-building as any auteur.

Hindsight and knowledge of history tint our perception of this world, however, with pensive lamentation. Extensive research into the town’s history reveals horrific, stomach-churning first-hand accounts of the systematic genocide of the town’s Jewish population during Nazi occupation barely a year after Kurtz’s visit, the immediacy of the danger, as Kurtz describes it, as unbeknownst to the subjects of his grandfather’s home film as it was to everyone else. Before the war, the Jewish population of Nasielsk stood at 3000. Post-war, that number stood at barely 100.

And yet, there is no memorial, no monument that stands to remember them or their existence other than a 16mm strip of gelatin-coated plastic. That is the power of film that Stigter, herself a film historian, is acutely aware of, and a power she distils over the course of this bewitching documentary.

Matthew McMillan

Three Minutes: A Lengthening is released in select cinemas and on Curzon Home Cinema on 2nd December 2022.

Read our interview with director Bianca Stigter here.

Watch the trailer for Three Minutes: A Lengthening here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS