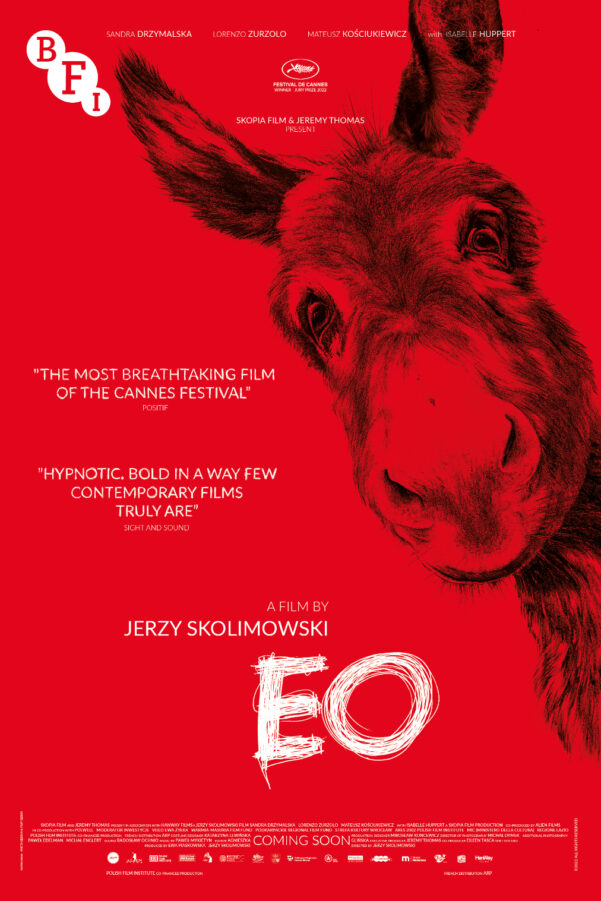

“It was made out of love for animals and nature”: Jerzy Skolimowski on EO

EO’s power comes from its exploration of humanity through the filter of a donkey’s eyes. We find our titular protagonist hurtled through the often callous whims of human greed, scattered amongst moments of tenderness and some of indifference. It is an ambitious narrative form, taking its cue from Robert Bresson’s 1966 film, Au Hazard Balthazar, which shuns traditional structures by placing the reactive character of EO at its heart, with humans, even the sympathetic ones, on the periphery of the film’s scope.

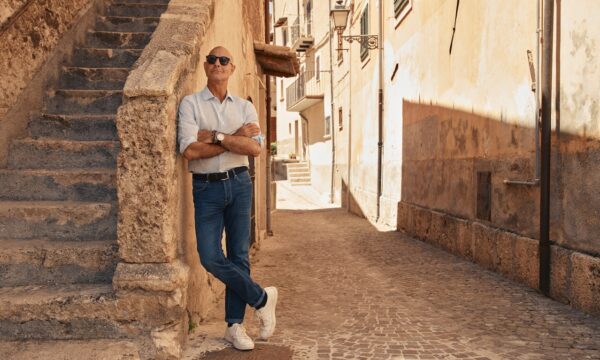

The Upcoming spoke to the film’s director, Jerzy Skolimowski, about the desire to work outside of the restrictively traditional three-act structure, the advantages and disadvantages of directing an animal, and how his own perceptions shifted as a result of making such a uniquely polemical film.

This is your first feature for a number of years, so what was it about this story that compelled you to develop and ultimately film it?

You’re right, it is seven years since my last film, and for seven years we were thinking, myself and Ewa (Piaskowska) – who is my regular co-writer and co-producer – were thinking about what our next project should be, so we had plenty of time to think about that. The main thing we agreed upon was that we didn’t want to follow the classic three-act narrative structure and all those iron rules that you have to introduce the characters in the first act and have a plot point in the 17th or 18th minute etc. We were bored with working like this. It reminded us too much of a clerk in the office! So we decided to try and find a different type of narrative, and we thought that perhaps if we used the animal character, that could be very useful in this process. At least you know a good chunk of the dialogue would be gone. So this is how it happened that we had this very experimental narrative.

What was the experience like of constructing the world as seen through the eyes of an animal? I’m sure some filmmakers would find it quite restrictive.

I didn’t find it restrictive, although, of course, we were more limited than if we were working with a human character,r as we could only imagine what the animal’s reactions would be, and we didn’t want to fantasise too much, so there were some limits of course. But we hope that, because of the many different situations in which our main character finds himself, the palette of reactions was rich enough to be quite truthful. I have received many congratulations from people who work with animals. They have praised our work saying it is a very accurate portrayal.

What kind of logistical problems arose from having an animal protagonist? Presumably a donkey isn’t as easy to direct as a human actor!

Well, there were some advantages with working with the animal, and some disadvantages. Advantages in that the donkey wasn’t asking all those questions which actors feel it is necessary to ask, and many times those questions don’t make any sense, so the director’s answers don’t make sense either! So the donkey didn’t ask any questions, which was good. On the other hand, communicating the tasks was difficult. It was mostly the manoeuvring from one point to another which proved difficult. We had to have several rehearsals more than we would have needed with a human character. But fortunately, contrary to the popular opinion that donkeys are stupid, they learn quite quickly what is needed from them. I also found some special ways to establish communication with the donkey. Every free moment of my time on set, which the director normally spends in his trailer smoking cigarettes, I spend with the donkey in his horse wagon. I found that I talked to them, just the way you’d talk to your pets. You don’t have a philosophical exchange of sorts, you just talk total nonsense, but in a very special tone of voice which makes the difference. I tried to be very gentle, very personal, and they understood that I was trying to create some kind of coexistence, and that this was a mission that we were preparing for and executing, and that worked quite well, I must say.

The relationship between the donkey and humans is central to the film. What attitude do you think the film takes towards humans? Is it positive, negative or neither?

I think the film shows, quite realistically, the different attitudes of people. Some people are very kind and understanding, some don’t care or even treat the animal as a living creature and treat the animal as an object, not understanding that they have very similar emotions to humans. They all want to have the feeling of security, of acceptance, of being appreciated and loved. But the film was made out of love for animals and nature, and I hope, as a result, that at least a part of the audience will change their view towards animals. There is one terrible thing going on in the world at the moment called industrial farming, which sees animals being kept in terrible conditions. They don’t see the sky, they don’t have the taste of the green grass. Subconsciously, when we started to work on the script for EO, myself and Ewa, who is also my wife, reduced our consumption of meat. Our consumption now is maybe only 10% of what we used to eat. Half of the crew working on the film stopped eating meat completely. I hope that the film will have this affect on at least a part of its audience. That would be the great achievement of this film.

Matthew McMillan

EO is released in UK cinemas on 3rd February 2023. Read our review here.

Outsiders and Exiles: The Films of Jerzy Skolimowski, presented in partnership with the 21st Kinoteka Polish Film Festival runs at BFI Southbank from 27th March to 30th April 2023.

Watch the trailer for EO here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS