Ai Wei Wei: Making Sense at the Design Museum

Ai Weiwei is an artist most famous (or rather infamous) for intentionally shattering a 2,000-year-old Han Dynasty vase. His latest exhibition, Making Sense at the Design Museum, presents a strikingly contrasting message to this provocative performance regarding the significance we attribute to cultural artefacts. This show highlights the urgent need to protect and understand our fragmented history. Surprisingly, since the 1990s, Ai has meticulously documented China’s artistic and architectural heritage, amassing an enormous collection of both priceless ceramics and seemingly trivial mass-produced items. In Making Sense, these vast collections are displayed as art pieces, inviting visitors to reflect on our collective identity, the evolution of craftsmanship, and the choices we make regarding preservation and destruction.

The exhibition is centred around five installations, each incorporating hundreds of thousands of objects arranged in vast six by ten-meter “expansive fields”. The first meticulously lays out neolithic hand tools, including axes, knives and chisels; the second, porcelain cannonballs from the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), which were, surprisingly, used as weapons of war. Most striking is the array of large, blue ceramic shards, the remnants of Ai’s own work, shattered when Chinese authorities demolished his studio in 2011. These fragments poignantly lie on the floor of his current installation, evoking memories of that act of destruction.

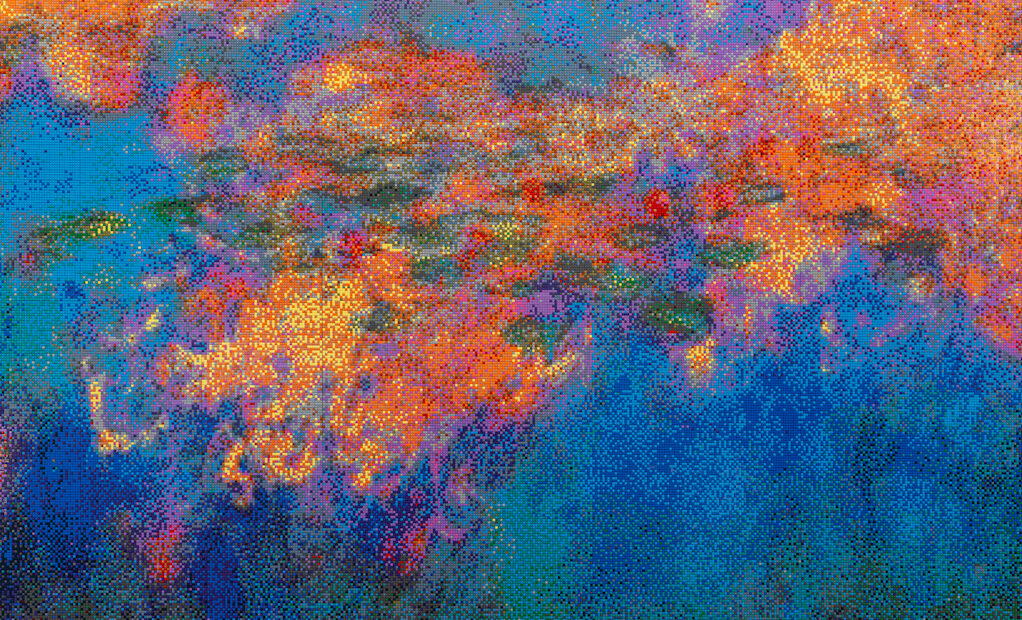

Towards the end of the room, beams from a demolished temple are transformed into a towering abstract sculpture, which emerges from a floor covered in Lego pieces. The final wall features a full-size, 15-metre-wide Lego replica of Monet’s renowned panoramic Waterlilies painting. From afar, the undulating colours convincingly capture the essence of the impressionist masterpiece. Yet, a conspicuous dark rectangle – missing from Monet’s original – signifies the entrance to the bunker where Ai and his father were incarcerated during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s in Mao’s China. These unsettling references to violence are a disconcerting undercurrent running through an exhibition anchored in themes of excavation and destruction. China’s massive industrial production is revealed as a metaphor for human suffering and exploitation, while modernisation and “progress” primarily wreak havoc on society’s most vulnerable members.

Two sinuous works grace the walls: one crafted from backpacks, paying tribute to the thousands of children who perished in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, with Ai attributing the catastrophe to faulty construction methods. The second is composed of life vests, remembering those who have lost their lives at sea as a result of the ongoing migrant crisis. The exhibition also features two life-sized toilet paper rolls, sculpted from marble and glass, as a 2020 response to our reliance on everyday items during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. This show is undeniably packed with thought-provoking concepts; while the assortment of reflections may appear somewhat chaotic, it never lacks depth or consideration.

The gallery also exhibits video footage of bustling Chinese freeways, accompanied by a striking photo series chronicling the rampant demolition and construction in the cities. While the photographs are visually captivating, they might be slightly overshadowed by the more noticeable installations. A Han Dynasty urn adorned with a Coca-Cola logo evokes Ai’s iconic act of shattering an ancient artefact, prompting reflection on the object’s value as an “irreplaceable” piece of cultural heritage. Ai’s Study of Perspective series, featuring a defiant middle finger aimed at iconic landmarks, is prominently displayed. In this photo series, he repeatedly performs the gesture as an artistic technique for gauging perspective. This piece, however, presents an overt and somewhat superficial (perhaps even crass) message in comparison to the rest of the exhibition.

Having endured beatings, imprisonment and exile as a result of his bold defiance of authority, Ai’s unyielding commitment to revealing violence and cultural vandalism in his homeland cannot be understated. The diverse components of Making Sense may seem somewhat disordered, embodying a mixture of ideas and concerns, but in their totality they imbue one with an unexpected sense of serenity: a result of their peculiarly meditative quality and undeniable beauty. This calming ambiance permeates the space, inspiring deep reflections on a lost past and our endeavours – potentially fruitless – to piece it back together.

Constance Ayrton

Ai Wei Wei: Making Sense is at the Design Museum from 7th April until 30th July 2023. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS