“She was one of the first who really put you in the mind of the murderer”: Eva Vitija on Loving Highsmith

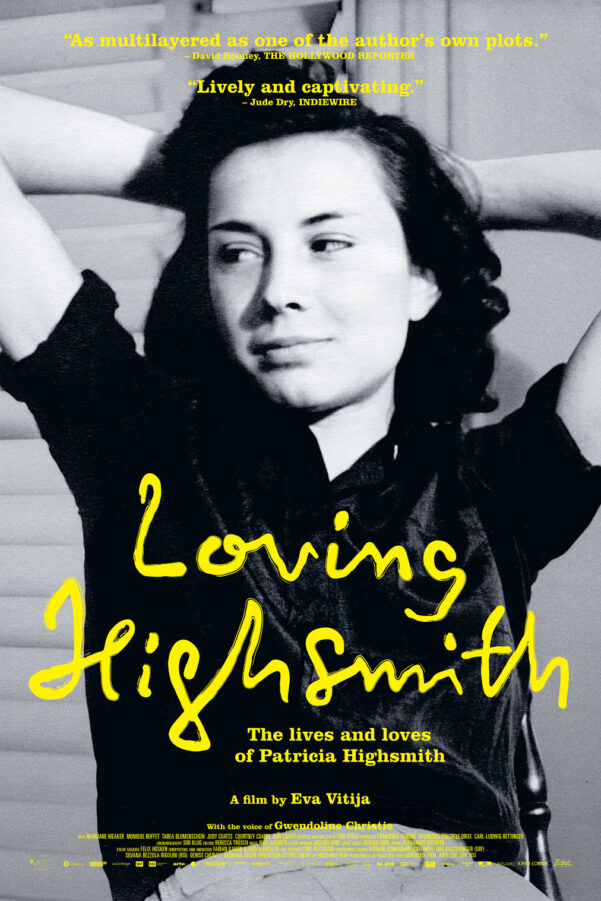

Loving Highsmith is the new documentary from Swiss filmmaker Eva Vitij that seeks to delve into the mind and life of author Patricia Highsmith. Most will be familiar with her work via famed adaptations: Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr Ripley (1999) and Todd Haynes’s Carol (2015), but there were more besides, with Tom Ripley being the most incarnated of her characters.

This documentary mines the writer’s personal diaries and notebooks, unearthed photographs, archival interviews and film excerpts, and combines them with recent interviews with family members and ex-lovers to understand the woman behind these murderous and often subversive stories – even by today’s standards. With Gwendoline Christie giving voice to Highmith’s words woven in with Vitija’s own narration, all unfolds in a lyrical and textured manner, exploring the complexity of the author as a person and tracing the connections between her and her work. It’s a fascinating new lens through which to revisit Highsmith’s work; for example, seeing Ripley as a version of herself makes the shapeshifting, queer nature of the character seem to slot better into place. Also remarkable is how groundbreaking the original text of Carol was at the time and remains now, when the idea homosexuality can lead to long-term happiness still seems not to be wholly accepted.

The documentary has come under fire for glossing over the racist and anti-semitic bent her later writings took. But, rightly or wrongly, the film doesn’t seek to rationalise all that was contradictory about Highsmith, but rather uncover her many sides.

The Upcoming had the pleasure of in-depth chat with Vitija about her compulsion to make the documentary, the mechanics of collating and threading the multiform material into a narrative, and her reflections on the connection between the writer’s personal struggles and her artistry.

Hi, Eva. I’m Sarah from The Upcoming. It’s such a pleasure to speak to you today. Can you begin with a brief introduction to Loving Highsmith? What can people expect when they watch it?

Eva Vitija: They can expect a more unknown side of Patricia Highsmith, which helps them read Patricia Highsmith in a new way, I would say, because her oeuvre was very much influenced by her life, which might not be as well known as one would wish.

As you say, everybody might be coming to this film with completely different levels of knowledge of her as an author. A lot of people might know her most readily from the books that have been adapted into films, like The Talented Mr Ripley, Strangers on a Train and Carol. Could you talk about your way in and the jumping-off point for you? Did you start with her novels or did you have some other connection? And why did you want to make the documentary?

EV: Actually, I started with a small episode from my childhood: when I went on holiday with my parents in Ticino, where Highsmith lived, my parents always mentioned this famous author living alone with her cats. I must have been around seven or eight, and I really wondered about that lady living alone with her cats. But I had completely forgotten about that when starting the film. I just found out that she was living in Switzerland, so all her unpublished works were in an archive in Switzerland. I knew some of her novels, but I was not the hugest Highsmith fan; when I started to read those unpublished writings, I was totally sucked-in, immediately, because I had so many questions about her. She was such a different person than I had expected. I might have had the typical Highsmith image of this old, very mean, dark, crime novelist, and I didn’t know much more. So I discovered a totally different person in those unpublished writings, and then it was clear that her private life, her love life, would be crucial to the documentary I wanted to make. And also you always have to ask yourself what you can add to the image that’s already there, because obviously there were already some biographies about her. And I thought now would be the last moment to catch up with her ex-girlfriends or her ex-lovers. That was starting point. And then I just started to travel, visit people etc.

There’s such a fascinating texture and poetic fluidity to the film that brings in all these different elements: the words from her diaries, narrated by Gwendoline Christie, your narration, archival footage, and all these incredible interviews. Where did you begin approaching people and finding all that footage? It must have been a really long process.

EV: Actually, the unpublished writings were the backbone of the whole thing. I started with that and, in parallel, I visited the family because I wasn’t quite sure who had the rights to all her writings and pictures. Because I was in Texas anyway for the film, I found out where the family lived, and they were actually pretty open to my request because they hadn’t been visited by anybody before. They just gave me some boxes they still had – they didn’t even know what was inside – and I discovered wonderful photographs of Highsmith as a child and as a young woman, some of which were not yet published. I also found a film reel, which excited me totally. Of course, I thought it was Patricia Highsmith material on real film, 16mm, and it would have been the discovery of the century! I couldn’t look at it, I had to take it to Switzerland. And I discovered it was only rodeo material, on a film reel. I was very disappointed at first, of course, because I thought I couldn’t use it, but, after a while, I realised that this whole rodeo background was actually quite important to discuss her family background and the kind of culture she came from. And it was this visit with the family that was actually the start of the film, because I wasn’t sure if there would be enough picture material. If you make a film about a writer, it’s always a problem that you have lots of text, but how will you tell the story in pictures? So I discovered that there were quite a lot of photographs. And I could start with that. But, of course, there were still huge quantities of her life which are not on reel.

What comes out through film, as you said, was that people had a very specific perception of her as a person, but she had a very different side as well – almost two sides of the same coin: she could be cold and reserved and rude but also dry-witted and funny, with this incredible imagination. What was one of the most surprising things you discovered about her along the way?

EV: I think I’d never discovered a person that was so contradictory. Like, if you find out something about her, the next day, you will find out the opposite. That’s very Patricia Highsmith. The thing that astonished me the most was probably that she came from a background that I didn’t really expect. There was a very short part in the biographies that already existed about where her grandparents came from, in Alabama, and I had from the start wondered where this topic of guilt in her oeuvre came from. I thought it was always a question of homosexuality, living with the guilt at that time because of being homosexual in a society that doesn’t allow it. But I had the feeling that it might also come from a more historical kind of guilt because the family had come from the south, Alabama, where they had a cotton plantation. And, obviously, that was something where you had slaves. So that was a bit of an astonishment in the whole history of Highsmith. Of course, it’s very far away from her personal life, because it’s the grandparents or even the parents of the grandparents who had that background, but I thought it was important to do some research on that.

Her homosexuality is a theme that permeates the film. The fact that the book that she wrote in the 1950s with a lesbian love story, The Price of Salt, was so groundbreaking because it had a happy ending puts into stark focus how slow progress has been, because there are still some stereotypes around the queer stories we read and see on-screen. Was that an interesting thread to pull out?

EV: Yeah, there’s, for example, this question that always repeats in every interview: “Why is she living alone? Why is she such a loner, a lone wolf?” – I think this stereotype definitely still persists about her life, because she actually said in every interview, “I’m not alone, I’m just living in the countryside. But I have many neighbours, I have many friends, I visit people every day.” I also visited her neighbours, and they told me she was extremely social, she was always there every evening, they even had to throw her out after a while. But somehow it persisted that she was this lonely wolf. I think that’s, for example, a typical homosexual stereotype, still persistent, that it’s not possible to have happy relationships or stuff like that.

The other element I found really interesting was thinking about how much her stories and her characters are infused with her own experiences. I love this bit where she says in the interview, “Basically, I am Ripley.” I mean, obviously not in the murderous things that he does, but in this way of playing a character and being a bit of a chameleon to an extent. That must have been one of the great things to look at and think about?

EV: Yeah, I think the identity topics for her and the insecure identity or shifting identity, the changing identity topic, which is always a big thing in all her novels, in different kinds of ways, comes directly from her biographical background. Also, just being able to look at society in a different way, to always see what’s the facade and what’s the abyss behind it – I think that comes from her biographical experiences of always having the experience of herself leading a double life, whether she wanted to or not.

What do you think it is about her writing that has made it so perfect for screen adaptations? People are still so fascinated by those stories still today. I’ve seen The Talented Mr Ripley countless times, it’s so complicated and so nuanced. There’s something about her writing that really captures people’s imaginations.

EV: I think she really thinks in a visual kind of way; she thinks in images and pictures. That’s one thing, and then there is the construction of the stories, which are very good for film somehow, and the characters are still fascinating because they were totally shocking at the time and sometimes not understandable. I think she was one of the first who really put you in the head of the murderer, as well. Of course, there was Dostoevsky before, but for that time, she was one of the first to do something like that. Now it is totally normal we are in the mind of the psychopath or murderer, but that was really shocking at the time. And I think it’s still kind of fresh to have something like that.

Maybe we can say a few words about bringing Gwendoline Christie on-board. She’s such a unique actress who plays many different types of roles, and has a wonderful voice for this. How did she come to the role, and why was she the right person for you?

EV: Actually, I just listened to voices first and I didn’t even know whom I was listening to because I really wanted to be open to all voices and really come from looking for a voice that would remind me of Highsmith. With Gwendoline’s voice, immediately, I was somehow reminded of Highsmith. Even though she doesn’t have the exact same voice or the exact same accent, but something in her voice is very similar. And then I looked at her name, and, of course, also the roles she chooses were kind of perfect for Highsmith because she doesn’t choose typical female roles: she always also plays with gender roles, and that was perfect for the film as well. And then, of course, she’s a great actress, and it was not so easy to get to her. The management was not that fond of making a small Swiss documentary, but she was a Highsmith fan, fortunately! And she even had met one of Highsmith’s biographers, so she was very interested in the project. It turned out to be a really exceptional experience to work with her because she came there and she was the absolute perfect Highsmith. We met in Romania, where she was shooting the series Wednesday, and it was such a wonderful two days working together.

Finally, what do you hope people take away from watching the film? There’s an immersive, poetic aspect to it, as well as it being very educational for people who don’t know much about Highsmith, but it also raises questions about where we are in society in terms of how we accept people of different sexual orientations and the idea of the artist. Does there always have to be a side of suffering in order to be an incredible artist? Throughout history, we see figures who create incredible work but struggle in their personal lives.

EV: I think, for Highsmith, it was a choice that she thought she could only work well and write well when she was struggling, when she had these great problems. She didn’t even want to go to therapy for long. She did try to convert, which was normal at that time, and also astounded me because this is all not so long ago. Our generation thinks everything was always how it is now, but this was 20 years ago and it was completely different. Highsmith, for me, is a bit of a hero because she subordinated everything she did under her writing. The writing was on top of all, and she was willing to suffer for that. So, for Highsmith, it’s this typical biography where she has this whole suffering for creating her art. I don’t know how her work would have been if she didn’t have that biography? It was always a question for me: how would she write now if she could live her homosexuality openly from the start and wouldn’t have that problem? I think she would have written completely different books; she probably would have been a great writer as well.

Can you tell us what you might be working on next? Do you know your next film, your next subject, or are you still thinking about it?

EV: Actually, I just produced a film that had its premiere last week. It’s called The Hearing and it’s about asylum hearings in Switzerland – but they’re generally similar in every country. It’s a very delicate situation where people have to tell their entire life story, and most are quite traumatised by fleeing. This is the film I’ve been working on for the last few months, and my own projects are still in the very early stages.

Sarah Bradbury

Loving Highsmith is released in select cinemas on 14th April 2023.

Watch the trailer for Loving Highsmith here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS