Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life at Tate Modern

Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life pairs, initially mystifyingly, the two artists, despite the fact they neither knew each other nor of each other’s art. But throughout the show a compelling thesis emerges of parallels between the two: both lived in the same time (af Klint 1862-1944, Mondrian 1872-1944); both were captivated by the natural world, with lifelong preoccupations with plants, flowers and trees; both joined the Theosophical Society (af Klint in 1904, Mondrian in 1909); both were interested in Rudolf Steiner’s teachings and wrote him letters; both were inspired by the 1905 book, Thought Forms, which may have incited modern abstract art as we know it; both were interested in macro- and micro-perception of the universe; neither saw a distinction between art and life.

Co-curated by Tate Modern director Frances Morris in her last exhibition, this is the biggest presentation of Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint’s work in the UK to date – an artist largely forgotten until around ten years ago. Af Klint’s idiosyncratic output has been drawing attention in the art world, with landmark shows at the New York Guggenheim and London’s Serpentine Gallery in recent years, and a flurry of books about her. A photograph of the artist in her studio circa 1895 shows something strikingly modern in her body language and lucid, penetrating gaze, the light irises melting into mere suggestion in the monochrome palette. A self-portrait of Mondrian shows something similarly intense in his eyes.

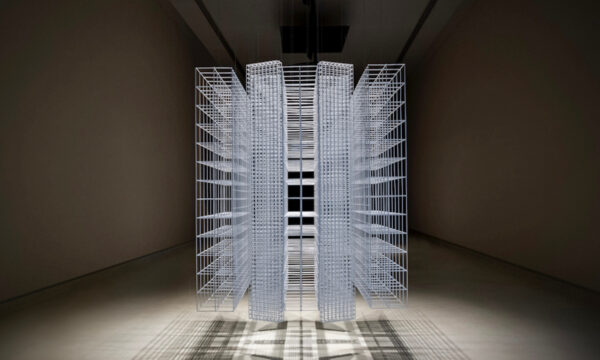

The nucleus of the exhibition is literally and figuratively the central room, titled The Ether, where an assiduous collection of materials from the two featured artists and contemporaries and influences is brought together. It is fascinating. There is a maquette of af Klint’s planned temple, created from designs in her notebooks, which would have been a place for education and research with resources like an observatory. For someone who spent their life dealing with the unseen aspects of existence, this building that existed only in imagination and potential is a striking representation of her powerful vision.

There are wild pictures from Carl Jung’s Red Book and an adorably meticulous diorama of Mondrian’s later New York studio, complete with minuscule paintbrushes and tiny glasses left on a desk. This room illustrates how the time both artists lived was full of explosive scientific discovery, from X-rays to radioactivity and electrons, that fundamentally shook world views, with people becoming aware that forces existed outside human powers of perception. The accumulated materials in this room are extraordinary and could hold the attention of a certain type almost indefinitely.

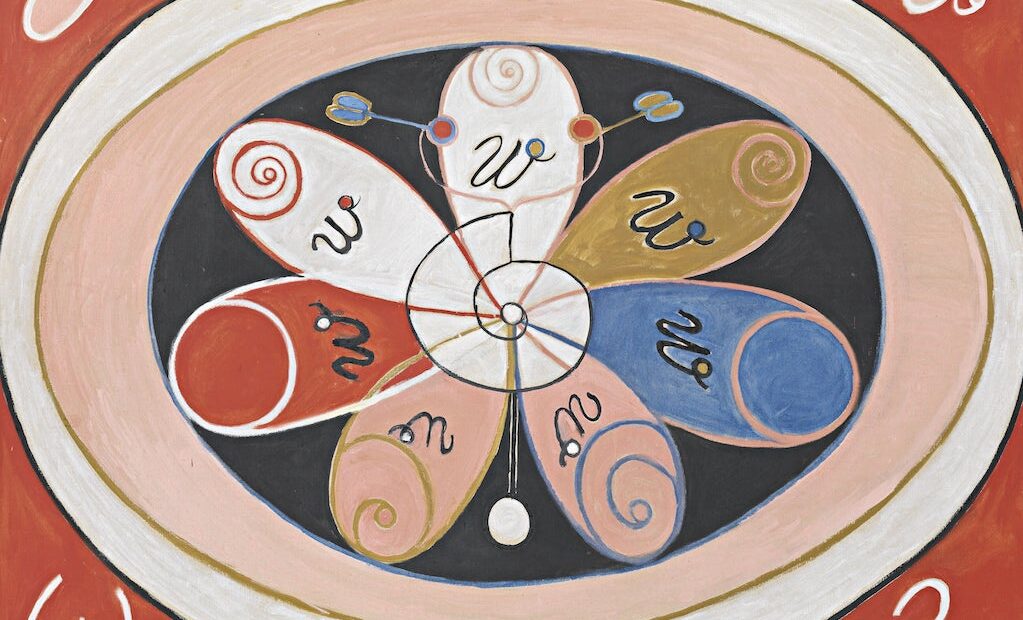

Moving loosely chronologically from the artists’ origins as landscape painters to their later abstractions precipitated by observation of the natural world – “the distillation of shapes to their underlying rhythms”, in curator Nabila Abdel Nabi’s lovely words – the rooms have been arranged thematically: pastels, flowers, trees and so on. Mondrian is better-known but really this is af Klint’s moment. Her watercolour Tree of Knowledge series (1913-1915) shows fantastical gardens filled with angels and symbolism that inspire close attention; World Religions (a series from 1920) displays something possibly akin to synaesthesia in translating the conceptual to the visual. The final room is given to The Ten Largest (1907), ten large-scale paintings that abstractly depict the stages of human life, made in anticipation of her temple coming to fruition. Like most of her work, they are colourful, dancing with symbolism and somewhat naïve in execution.

Af Klint said that she worked with several spirit guides to produce her oeuvre and, kooky as it sounds, some of the pieces do appear to predict the future. She stipulated that her work should not be displayed until 20 years after her death, as the public was not ready for it. It’s taken considerably longer than that, but she is now getting recognition for her singular vision. The slightly eccentric pairing with Mondrian is used as a way of drawing out af Klint’s creative gravitas by aligning her with a familiar, respected artist. Ambitious, enigmatic and visionary, would she have predicted this show? Quite possibly.

Jessica Wall

Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life is at Tate Modern from 20th April until 3rd September 2023. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS