Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power

While film theorist Laura Mulvey spoke of the male gaze – ie the objectification of female bodies in front of the camera as a byproduct of the over-dominance of men behind it – in the 1970s, it took the #MeToo movement for the discourse to actually provoke some change in the way women are portrayed on screen.

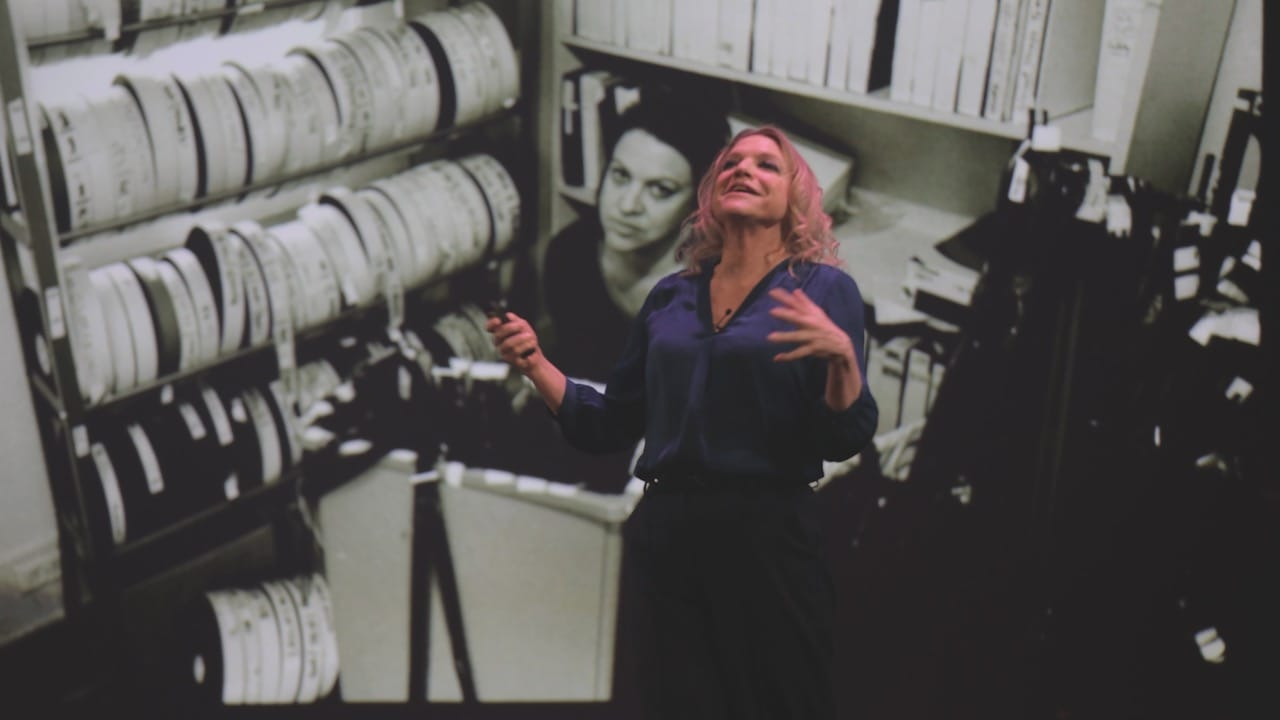

In 2018, filmmaker Nina Menkes addressed several of her peers at festivals when she held an illustrated talk on “the visual language of oppression”. Now she has taken the material she gathered for her presentation and turned it into a documentary.

Using over 150 clips that span almost the entire history of film, Menkes exposes the power imbalance of looking versus being looked at, the role that light, shot sizes, editing and sound design play, as well as the harmful effects this bombardment of images of subjugation carry over into real life. As impressive and simultaneously shocking the sheer amount of evidence for each proposition is, Brainwashed doesn’t content itself with archival footage. A number of female filmmakers are given a chance to speak and share their experience working in this environment: Catherine Hardwicke, Eliza Hittman, Penelope Spheeris – and Menkes herself.

When the director repeatedly references her own fictional work as counter-examples, the picture unfavourably digresses towards self-promotion. It should be evident that one cannot assess one’s own work unbiasedly and with the same scholarly attitude that is displayed towards others. Perhaps if Menkes had also spoken to some of the filmmakers whose productions she analysed and critiqued, this approach would have added a new layer to her film: intent and awareness.

Some of her subjects are not afraid to broach uncomfortable truths. Filmmaker Julie Dash, for instance, concedes that female directors are not above reproducing the exact same visual language imparted to them. Quoting Audre Lorde, she warns: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” But when a clip of Titane is thrown into the mix, without context or notice of the dismantling of gender that actually distinguishes this film, it begs the question of whether this criticism is of a feminist nature or that of a morality police.

It is acknowledged that the majority of the cited films are Hollywood productions and there is no claim of universality. Still, for a product of current feminism, the lack of intersectional thinking is somewhat bewildering. When a scene in 1975’s Mandingo is addressed as “the exception that proves the rule”, there is no mention of the fact that the male body that is being objectified is black, paradoxically proving many of the film’s earlier points about power. The camera that feasts on the flexing muscles of the beach volleyball scene in Top Gun is infamous for its blatant homoeroticism. Again, Brainwashed operates on an assumption of heterosexuality in its blanket statements about the men behind the camera.

But of course, Feminist Film Theory is an entire university course that cannot be summed up in a single documentary. Menkes sets out to examine the relationship between sex, camera and power in this film and that she delivers.

Selina Sondermann

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power is released in select cinemas on 12th May 2023.

Watch the trailer for Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS