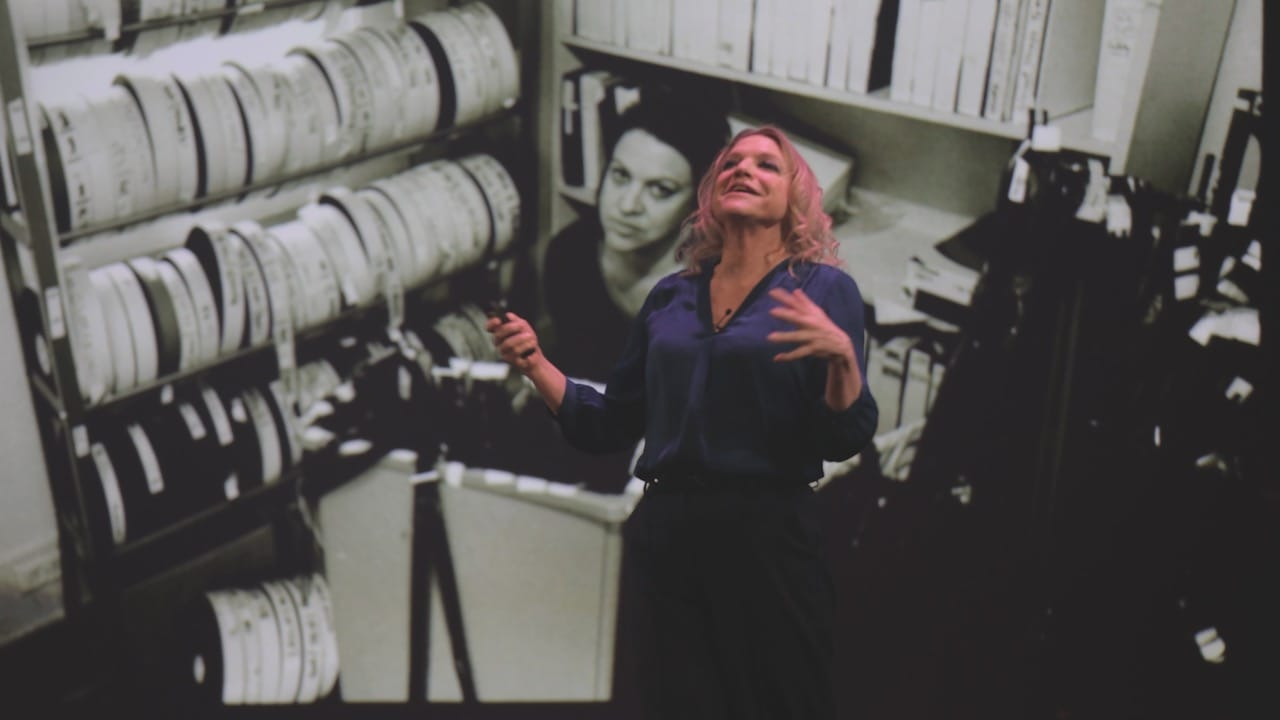

“If the people controlling the majority of the media made are almost all white, heterosexual males… then what happens to our world?”: Nina Menkes on Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power is the groundbreaking new documentary from filmmaker Nina Menkes, which delves into the murky waters of how the pervasive male gaze in filmmaking has not only shaped the portrayal of women on-screen since cinema’s inception but also had a detrimental impact on the perception and treatment of women in the real world.

Expanded from a teaching tool for her students, the documentary uses the aid of over 200 film clips from Hollywood classics to more experimental indie works, different genres and time periods, to delineate precisely how male perspectives, including screenwriters, directors of photography, directors and more, infiltrate everything from shot design to character development, to sexualise and flatten women into two-dimensional objects time and time again.

Menkes then also makes a further connection between the impact of these images on the way men view then opposite sex – and indeed how women view themselves – and the ubiquity of female-directed sexual violence in society, by portraying women as sexual objects to be used and exploited. In presenting the physical elements that produced these representations, the film is able to build an evidence base of how film language can perpetuate harmful ideas.

While the documentary touches on how the #MeToo movement brought many of these issues to the fore, it also suggests that not as much has changed as one might think, with even work from female filmmakers at times reproducing the same techniques. However, the film does provide a glimmer of hope that, by opening up space for dialogue and fearless reassessment of the film canon, there’s a far richer wealth of female experience to be mined for the screen.

The Upcoming had the chance to speak with Menkes ahead of Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power landing in UK cinemas alongside a retrospective of her films, to hear more about her compulsion to make the feature and the reverberation of its message through the film world.

Could give us a brief introduction to this absolutely fascinating documentary? It’s so eye-opening and has so many different elements to it that really get you thinking.

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power is a clip movie that includes almost 200 film clips from various movies, starting back in 1896 and going all the way through to the present. These films are really the masterpieces of world cinema from known directors – the films that won Cannes and the Academy Awards – and we examine how shot design in these movies actual physical elements of shot design, like framing, lighting and camera movement, collude and collaborate with the twin epidemics of sexual assault, sexual abuse and employment discrimination against women.

And, of course, as we see in the film, it evolved from a talk that you originally put together. Can you tell us a bit about what the process looked like of transforming the content from your talk into this broader documentary?

The talk was something I originally developed for my students. I teach film production, and I put together a series of clips – around ten clips – to show my students what I mean when I say that shot design is gendered. This was for my production students, people who are getting ready to make their own films. I never thought of it as anything beyond the film school classroom. But with the advent of the #MeToo movement, the US federal government’s investigation into the Hollywood studios’ extreme and illegal sexist hiring practices in 2015, and the #MeToo movement in 2017, there was an explosion of interest in the topic I was covering. I started getting invited to give the talk all around the world, and, during those sessions, people were begging me to make it into a film. So I had to start thinking, “How would this look if it were an actual feature film?”. The first big difference was expanding from ten film clips to 200, and we also brought in about 23 influential filmmakers and thinkers to lend their perspectives to the questions at hand. Turning the talk into a film was a process of really expanding and deepening the talk and putting it together in a highly cinematic way.

The thing I find most striking about your film is how the connections between how women are portrayed on-screen and perceived and treated off-screen are quite subconscious, and only by pointing them out and naming them can they become clear. It’s groundbreaking to see all of these phrases we’re familiar with, like the male gaze and objectification of women, delineated in such practical detail. Did you feel like your film was groundbreaking, that there really hasn’t been anything like this before?

Thank you for saying that. Yes, I think it has been quite convention-shattering and shocking to a lot of people – not just average filmgoers but also high-level film scholars, cinephiles and filmmakers. The director of the Sundance Film Festival told us that he would never watch films the same way again, and I’ve heard that from other highly sophisticated filmgoers and writers. Everyone was sort of aware, but that sort of awareness is very different from seeing 200 film clips, one after another, and breaking it down into clear, easy and irrefutable points that you can apply to any film you see. Based on the reaction, it seems to be causing an earthquake in the film-going experience for people, from those who just enjoy watching movies to film festival directors, who see 300 films a year.

On that point, I’d imagine, in terms of reactions, you’ve probably had a full spectrum: some people might realise they’ve never watched films in the right way, while others might push back or resist the message you’re delivering. Have you seen that happen, and how do you respond to it?

Yes, there has been pushback, anger and nastiness towards me. I interpret this as an expression of the pain and destructive nature of these techniques in the film. Instead of just seeing it as a sexy movie, we show that this impacts our real lives, from our ability to get a job to our own relationships, sexuality and most intimate moments. This impacts us as human beings in our real lives. There’s a lot of pain when you face it, and some people can’t deal with that. They don’t want to feel the pain or accept that it’s true. So, the go-to position is to kill the messenger. I’ve been attacked personally and told I’m narcissistic for including a few clips of my own films, which is hilarious because there are 200 clips in the entire film, and only a few are mine. There are also 30 examples of how to do things differently in the film. This tells me that some people either turned it off because they couldn’t stand it, or they watched the whole thing and were so blown away that they couldn’t remember what they saw. So the easy thing to do is attack the filmmaker because no one can really attack the argument, which is airtight.

It was really fascinating to consider the power of film, in the sense that you’re entering people’s imaginations, people’s psyches, and the responsibility that comes with that – because I’ve never really thought of a film or filmmakers in that way. You often think, “Ok, well, this is your piece of art. You can make it however you like, and whether people like it or not, is their choice” but, actually, particularly considering Hollywood studios and the money that’s behind them and how extensive the consumer base is of that content, should there be a greater acknowledgement of the responsibility of filmmakers?

Yeah, it’s a very powerful art form, and it’s concentrated in a very small number of hands. The people who control it and create the media come out of Hollywood, and there is definitely a huge responsibility that goes with that. The ideology of “the creative person can do whatever they want” is a nice idea in theory, but it’s quite problematic if the people controlling the majority of the media made are almost all white heterosexual males with one single perspective. Then what happens to our world?

Although the majority of the film is quite critical and in some ways pessimistic, towards the end you flip it around and say, “Well, hang on a second. If we acknowledge these issues, how much can we actually open up new and interesting spaces for different storytellers for different types of storytelling?” For example, by bringing women’s experiences to life on-screen and in a way that is much more authentic and genuine, what new films could we see in the future? Was that something important to you as well?

Yes, very important. We talked a lot about the end and how to bring some hope into the end without being saccharine about it. And one of the things we felt is that we wanted to also express some of the rage, and rage also has an energy of hope because the opposite of that is just depression: you don’t want to get up in the morning because you’re not a subject. How many women came out of film school wanting to be directors that just gave up and maybe became script supervisors or maybe, at best, editors – certainly not DPs and directors – until very recently? There was almost no chance to make it. So that’s extreme depression. Transforming that into rage and then into hope is what we were hoping to express towards the end of the movie.

From your experience, do you have a positive outlook on the future? Do you see that things are starting to go in a better direction, with the mention of the Oscar-winning Nomadland (Chloé Zhao’s film), and how that seems symptomatic of shifting times? Or do you feel like we are still a little bit stuck, even post #MeToo, with very slow progress – a “one step forward two steps back” kind of thing?

Well, I think both are true. I mean, I think there’s reason to hope. I’ve seen it in my own life; my own work has been getting a lot more attention all of a sudden because suddenly women directors actually count for something. I see it all around me that you see many more women directors getting hired for projects – you see it a lot. Also, in this realm of TV, we’re still not seeing it in the realm of the really big budget. You see it, though, in festivals. Festivals are now embarrassed if they have a slate of all-male directors, or even 95% [all-male] directors, – they’ll be embarrassed. Well, a few years ago, they weren’t embarrassed. It was just the status quo. So, have we seen change? Yes. Do we still have a long way to go? Yes. So, you know, both things are true.

One other thing I wanted to ask about was the use of intimacy coordinators, as you have a great interview with Ita O’Brien. Although it’s still divisive, would you say that’s also another sign of people accepting these issues on-set and finding ways to address them and solve them? And that could be one of those ways?

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, you know, a few years ago, there was no such thing as an intimacy coordinator. It just didn’t exist. You know, now it’s divisive. Some people are pro, some people are con, but the fact is there’s a discussion about it. And it’s not taken for granted the way it used to be. Like, they’ll have a naked actress – female actress – on-set, surrounded by an all-male crew; then, surprise! Because, guess what, it’s a rape scene… “I found out after we were halfway through the scene…” I don’t think that’s going to happen anymore. And it’s absolutely not a normal, everyday occurrence.

The film also raises the point of the idea of nostalgia itself somehow being quite a dangerous thing, that we’re not able to go back and reanalyse revered films from a fresh perspective for fear of cancel culture, provoking culture wars etc. But, actually, we can have these discussions, and it’s healthy to have these discussions.

Yeah, it’s really important. And you don’t have to be afraid of it. You know, sometimes people are afraid of consciousness. I heard David Lynch once talk, and he said he didn’t want to go into psychoanalysis or therapy because he thought if he became too conscious, it would ruin his films, which are very unconscious-driven. I really disagree with that. I feel like consciousness is never a negative thing: it’s transformational. And, don’t worry, there’s always more unconscious there. You’re not ever going to get to the end of the unconscious. But the more light that is shown on things, the more things are illuminated, the more we can really expand to areas that we might not have even imagined were possible.

Did you have any response specifically from any of the directors’ work that you included in the film?

The only director that directly responded was Jay Lo, the director of Bombshell. He wrote me a very long email explaining exactly why he shot the scene that way. But then he said, at the end, “This is off the record, so you can’t share it.” I was like, “Okay…”. So, yeah, we did reach out during the course of the filming. We reached out to almost all the living directors whose clips we included, and the ones who said yes are in the movie. The ones who are not in the movie said, “No sorry, busy.” So, basically, those who might have objected to what I was saying already eliminated themselves by deciding not to participate.

And, finally, what does it mean to you to have the film now being released here in the UK? And do you know what you’re going to be working on next?

NM: Well, I’m very, very excited about the UK release. It’s coinciding with a retrospective of all my work, which is a huge honour, and I’m super excited. I hope people have a chance to explore the films. I do have two new scripts, and I’m very much hoping to get them financed. So we’ll see what happens.

Sarah Bradbury

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power is released in select cinemas on 12th May 2023.

Watch the trailer for Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS