City of London Sinfonia: Divergent Sounds at Queen Elizabeth Hall

“There are eight billion neurodiverse people in the world. Who decides who is in the normal group?”

A long horizontal score stretches across a table in the foyer of the Queen Elizabeth Hall; it is structured with blue and green shapes, which are filled with small, different coloured symbols. This is a graphic score, and the key reveals the multitude of sounds that the audience will imminently encounter, including “echoed voices”, “noise fragments”, “samples” and “intense moments”. On an adjacent table there is an enticing selection of coloured pens and stickers. The audience are asked to take a printed out sketch of a body and mark on the drawing where they feel the music impacts them physically. The stickers are traffic light coded and signify levels of the listener’s approachability, including “happy to chat”, “approach with sensitivity” and “please keep distance today”.

Divergent Sounds with the City of London Sinfonia was instigated by Dr Virginia Carter Leno. It is part of a research project at King’s College London that explores the different ways neurodivergent people’s minds work. Leno writes in the programme that she wanted to work with creatives to “capture the lived experience of being neurodivergent” in an accessible way.

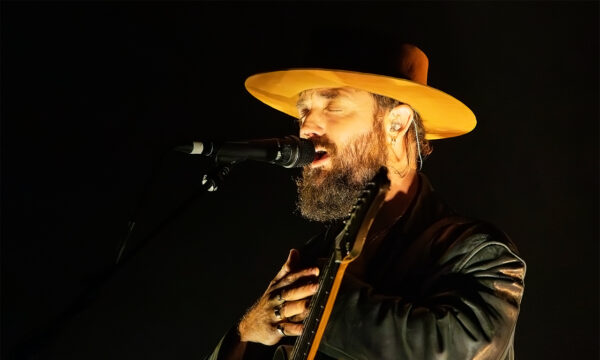

The musicians of the CLS are dressed comfortably and bathed in azure and rose-coloured lighting. Intriguing wires snake around the instruments, and a light pitter-patter of a drum kit accompanies a clarinet noodle as the audience walks in. A British Sign Language interpreter starts to communicate with an audience member: the pre-show anticipation feels invitingly far away from typical orchestral concert rules and regulations.

The ensuing 80-minute journey is as educational as it is engaging. The ensemble cuts between Stephanie Lamprea’s radiant soprano song and recordings of interviews with a focus group of 25 neurodivergent people. The interviews cover a range of experiences of neurodivergence: how people process information differently, the experience of sensory overload, the societal pressures to “mask”, the necessity for resilience, the potential for creativity and debunking myths around neurodivergence and empathy.

Technology and the musicians work in tandem to reflect the lived experience of sensory overload. Jan McGregor’s libretto spits out verbs – “grinding, screeching, irritating, unrelenting” – which are caught and repeated on the screen. The musicians rustle their instruments and paper, repeating “are you ok?”, as a soundscape rises in intensity, the overstimulation of societal expectation seeping into the audience. The soprano’s wrists are wrapped in gloves with sensors that convert her movement to MIDI-data, allowing her to adjust the reverb of the sound through gesture. The effect is unlike anything most have experienced in a concert hall. It is transfixing.

The beauty of the performance is in the aural celebration of being neurodivergent. The harp and clarinet gently dance at the description of the “childlike wonder retained”. The trumpet sings in triumphant self-acceptance as the interviewees speak of their pride over their enhanced creative potential, as well as their interminable resilience in a world that feels slippery and uncertain.

There is a reverberating feeling of hope and generosity when leaving the hall: hope for an investigative society that strives for an holistic approach to work; hope to reach a point where labels are unnecessary and self-advocacy is the norm. The performers are asking us to ask others, “What can I do to make you feel more comfortable today? And here is what you can do to help me.”

Ellen Wilkinson

Photos: Southbank Centre

For further information and future events visit City of London Sinfonia: Divergent Sounds’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS