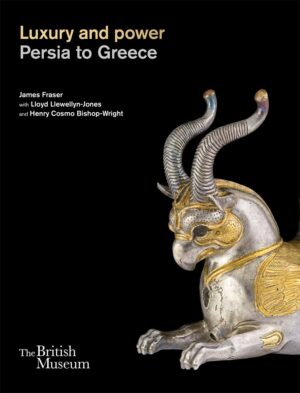

Luxury and Power: Persia to Greece at the British Museum

Exploring the relationship between luxury and power in the Greek and Persian civilisations between 600-200 BCE, the British Museum’s major new exhibition, Luxury and Power: Persia to Greece throws into sharp focus how luxuries shaped the political landscape of Europe and Asia. In this impressive gathering of some 160 objects, one discovers how the Royal Achaemenid court of Persia used such items to mark their authority and forge alliances. Initially, the Greeks viewed the eastern empire’s liking for exquisite objects as a sign of their enemy’s decadence. However, in time, democratic Athens is revealed to have become increasingly entranced by Persian luxuries. Finally, Alexander the Great would conquer Persia, bringing into being the Hellenistic age that saw the fusing of Eastern and Western styles of luxury.

The background to the exhibition are the Greek-Persian Wars (499-449 BCE), which pitted the Greek city states against the Achaemenid dynasty kings. Ultimately, the Greeks emerged victorious, leading to most accounts of the conflict and the Persians themselves being written by Greek historians like Herodotus (a frequent point of reference here), who viewed the vanquished foe to be extravagant and corrupt. This clash of civilisations is immediately alluded to in the opening room at the British Museum, held in the Joseph Hotung Great Court Gallery. One meets two statue heads staring into each other’s eyes like pugilists before battle commences, one made of stone and identifiably Persian, the other, a bronze Greek Apollo. Closer examination however reveals the Persian character to be adorned with a Greek-styled wreath, thus illuminating the cultural fluidity that would come into fruition in time. The years when the Persian empire was at its zenith from around 500 BCE provide the setting for the opening of Luxury and Power. A short film shows how purple pigment, extracted from a sea snail’s gland, was more expensive than gold, the colour symbolic of power across the Achaemenid ruled lands.

In the second room, the visitor finds Persian influence subtly seeping into Greek society. A water jar from around 400 BCE sees the depiction of a woman beneath a parasol – an item associated with Persian kings. Greek men regarded parasols as unmanly and yet they became popular with Athenian women. Persian men’s liking for eye kohl is said to have been similarly dismissed as effeminate by male Athenians but came to be fashionable with their wives.

A constant feature throughout this exhibition are the large, luxurious drinking vessels known as rhytons. Resembling horns and made of gold or silver, they featured griffins, bulls and human portraiture. These ornate Persian banqueting cups were long viewed as the epitome of ostentatiousness by the Greek city states, whose ceramicists for many years are seen to have preferred to create pottery rhytons in the form of red, white and black painted ram and boars’ heads. There is a particularly historically significant drinking cup on display shaped into a Persian defeated in battle, his face etched in pain.

The artefacts in the third and final room shed light on how Alexander the Great’s vast empire (he himself would die mysteriously in 323 BC) saw the unification of Eastern and Western ideas of luxury, bringing together a vibrant cultural melting pot. Having conquered Persia and set Persepolis, its capital, ablaze, Alexander ensured his artisans adopted and adapted Persian craftsmanship to harness his reputation within his new domains.

As the British Museum’s exhibition nears its conclusion, the magnificent Panagyurishte Treasure clamours for attention. Discovered by three brothers in Bulgaria – originally home to the ancient Thracians – in 1949, it’s on loan from Bulgaria’s National Museum of History. These eight glittering gold rhyton drinking vessels and a bowl weigh in at a combined 6.2kg. Believed to have belonged to the Thracian King Seuthes III, they are a fusion of Persian, Greek and local styles. Elsewhere is displayed another fabulous artefact, a delicate gold wreath decorated with twining oak twigs, bees amongst the leaves and cicadas. Discovered in Turkey, it dates from the middle of the 4th century BCE, some years after Alexander the Great’s passing. There is a posthumous portrait statue from Egypt of the Macedonian warrior king who conquered Persia, with visitors learning that even Alexander wasn’t adverse to the adoption of Persian customs: he came to insist on having courtiers prostrate themselves before him, apparently the cause of much consternation.

This frequently dazzling British Museum exhibition commandingly argues the extent to which Persian luxury had an enduring effect on Greek cultural values. The exquisite craftsmanship on show will delight the public whilst highlighting how luxurious goods continue to hold an irresistible lure in the modern era, their ownership bringing social cachet.

James White

Luxury and Power: Persia to Greece is at the British Museum from 4th May until 13th August 2023. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS