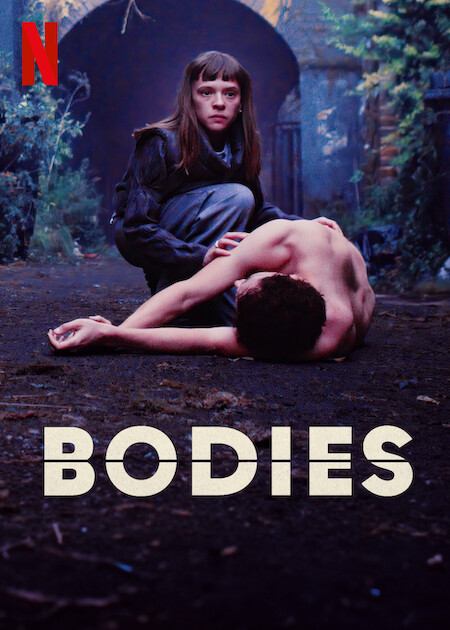

“I don’t think I’ve seen a mystery or crime so clearly about love”: Jacob Fortune-Lloyd, Amaka Okafor and Paul Tomalin on Bodies

Bodies is a complex sci-fi crime thriller that merges large periods of history through the narrative. The story includes scenes from the Victorian era, the midst of WW2, the present day, and then 30 years into the future, whilst there remains a murder victim who keeps showing up in the same space in Whitechapel, London during those four points in time, in turn binding the narrative with one cohesive line of investigation.

This eight-episode series has been created by Paul Tomalin for Netflix and is an adaptation of the DC comic and graphic novel of the same name by British writer Si Spencer. It includes a brilliant ensemble cast, who bring to screen a sinister story that is part drama, part murder-mystery, part sci-fi and part period drama.

The Upcoming heard from Jacob Fortune-Lloyd (who plays DS Whiteman), Amaka Okafor (DS Hasan) and writer Paul Tomalin about this new show. They divulged the intricacies of the narrative as it spans huge timelines, delves into the police work that changes and adapts over time, and reveals one common thread: an unidentified murder victim.

Can you tell us about the history of Bodies and how it came to be?

Paul Tomalin: I think we had no idea what the patchwork was going to end up like, so we kind of went in all guns blazing and tried to see how thrilling it would be. It was originally a graphic novel by the author Si Spencer, and it did very well; it had a cult following. Then Will Gauld came to me and said, “We want to do the show. There’s four different cops and a murder and it’s the same but over four different time lines.” I immediately said “No”, but as I walked away I thought I was an idiot because Jack the Ripper stuff, the Blitz stuff , Line of Duty stuff, the future, the dystopian stuff – this was wild. The unique ingredients were too good not to be bound together. At first I thought it was just too strange to exist, but then I thought I’d love to get involved in the research, these timelines, absorb it all and put it on the page.

What is it like building a series where you’re a lead, knowing there’s someone else in the same series who’s also a lead, but you have no idea what’s going on?

Amaka Okafor: It’s really cool because it feels like a team sport: it feels like you’re sharing the responsibility. I’m really looking forward to seeing what everyone’s been up to.

Jacob Fortune-Lloyd: Sometimes it feels like you’re in your own story and it’s the only story, but then you have this wild knowledge that there’s this whole bigger world around you.

Paul, in terms of the research, the show delves into these four different eras – which did you feel most comfortable in?

PT: By default, the one with the most research is the 1890s due to Jack the Ripper really – it’s very well documented; but in terms of joy, it was probably 1941. I was researching it during Covid and relating it to the Blitz. It was fascinating to see the similarities – there was so much misinformation. Also it was the time of film noir, all those great black-and-white movies, too.

How did Whitechapel lend itself to be the scene of these crimes over these different time periods?

PT: The way it’s evolved as a melting pot over the 20th century is fascinating. In 1890 it was all about the Irish immigration, and 1941 it was filled with a Jewish population, and it’s this place where conflicts have played out. It’s one of the most alive and thrilling places in Britain.

Jacob, what were some of the skills you had to learn to play a detective?

JFL: I spent a long time trying to work out how to do this lighter trick. It took a long time – I’m very proud of it! It’s in the show. I felt like he was a guy that had a lot going on all the time and would need some sort of physical manifestation for his restless energy, so there was just something so cool about the lighter – something gun-like and metallic. I loved playing him, but it was a very physical performance; there was a lot action and I had to get in shape, do a lot of running and work with a brilliant fight choreographer.

Amaka, we immediately see your character thrown into the thick of it, running, doing all these stunts, being knocked down… Was that all very new to you in terms of preparation?

AO: I really love running, so I enjoyed that, and I suppose the challenge of trying to be believable was trying to use the stuff to be real. It was all in the script, really. I’ve played a lot of police detectives before, for some reason, and this one there’s just so much more. I know it’s a police drama but very quickly it becomes a million different things, and you are this person trying to figure out this mindbending puzzle, and it’s all about the quest.

How important was it for you that Shahara’s religion was just a part of her identity and not everything about her?

AO: Really important because I come from a family with lots of different religions within it, and some of my closest family members are Muslim, so I’m just tired of seeing people put in a box because of something like that, and the refusal to look any deeper. So I feel like she’s a single mum, she lives with her dad, she’s mixed race, she’s a detective, she’s a working mum… She has all these other sides to her personality, where she’s all those things, and it would be sad to just stop at the Muslim thing.

Jacob, religion plays a part with your character too. How does his experience of being a Jewish police officer in wartime Britain translate?

JFL: It also relates back to my own family background. My mother’s side came over in the early 1850s and all lived in that area. They were butchers and tailors and moved around all the time as they didn’t own their own property, and life was tough, so I know a bit about them and that helped. Judaism is very important in this, both by the way he is seen, the anti-semitism he receives, and the way he puts up a wall, closes his heart. When we meet him, he’s walled-up, closed-off and cool. He’s grown up in poverty and been a fighter; the way he’s been treated he’s got a very antagonistic relationship with God, which I think comes into it, which I like. There wouldn’t have been many Jews in the police force and he would have felt very alone.

That isolation come into play with each of the characters. Can you talk about that?

PT: The fact is that its an ensemble piece, yet in most of it they are not interacting in any way, shape or form with each other. They are all outsiders, but all feeling a very acute sense of isolation, both in their social lives but also in what the case presents them with. It’s what I love about the show: that they actually aren’t going through it alone, even if it’s with someone 50 years in the future. Theres something very cohesive and compelling about that, and then seeing how they realise and find each other in some shape or form is very emotional.

You pick up all those issues that have been rife within the police force: anti-semitism, homophobia, misogyny. Why did you want to explore those things though the lens of the police force, and what do you see as potential issues in the future?

PT: Each timeline deals with the bigotry of its time. You had to give them something that separated them so you could relate to them. In terms of the future, you’ve got to heighten what is now, so we heightened the elements of diminished responsibility, the risk of privatisation, the risk of technology. The thrill of of each timeline, though, is also the technology – fingerprinting just came in in 1890, ballistics in 1940s, DNA now, from the 80s onwards – so what is the future thing that would give us an insight that the other cops would be robbed of?

Jacob, did the production design of the 1940s police station help you get into that world?

JFL: It was a great location in Bradford. It’s not what you immediately imagine a police station to be like. This was a tiered, open space, different levels with people looking down on each other. It was a very male environment, very macho, a very smoky environment with everyone there in their crisp suits, their hats and the phone switchboard. The geography of the space was the main thing, and it was really well used – everyone looking at each other all the time. And Whiteman is such a cagey character; he’s smooth, but he’s got eyes in the back of his head at the same time, and that really heightened that.

Can you tell us about the moustache? Were you happy to sport that on set?

JFL: It took a while to convince me. It’s a nice ‘tache, but at the beginning I was thinking, “Is this too obvious? Too sleazy?”, and then thinking, “I also have to wear this outside of work for months” – and that pencil moustache is a serious look! There’s so much the hair and makeup and costume give to the character. Before you step into that and look in the mirror, all finished, and the crispness, the sharpness, the pride, the armour, the fact that these guys wouldn’t have had many suits… They looked amazing though, because the ones they had they looked after so well, and the fabric is really high-quality – it just tells you so much about someone. I looked at myself in the mirror and felt like a different person.

Amaka, you’re the only one in the present timeline. Was it helpful for you to look into the Met as it is now?

AO: As I’ve played a police officer before, that side of it didn’t feel difficult. To be in the Met today and what someone like Shahara would be up against – like getting pulled in for particular cases because of her ethnicity, because of her religion, needing to look a certain way, asking her to put a headscarf on to be able to connect with someone – that sort of thing was new to me and interesting.

Viewers are looking at it as a show on this enormous scale, but when you were filming your localised scenes, were you aware of that?

AO: I was really aware of it. There are certain shots where it was necessary for me to know what Jacob had done for how it was going to be edited, so sometimes, before doing a scene, I would watch what he had done, and it felt really grounding and I felt less scared because I felt then that it wasn’t just me. Without giving too much away, Shahara is at a point in time where the events of 1890 and 1940 have already happened, and so she’s on the hunt for clues, and I felt very aware that these two people had lived because I am trying to find out stuff about them.

Paul, you’ve been adamant this is not sci-fi or one genre or another – how did you seamlessly blend all these genres together and make sure it was never boxed or marketed as one thing?

PT: Right up front, the danger was as you jump between strands, it’s like channel hopping, so it was about what makes it cohesive and that mystery really binds it and this mantra that runs through it: “Know you are loved.”

JFL: When I read the script the first time, there was so much going on. It’s a mystery – a puzzle – with some sci-fi elements, and in some ways it’s quite “heady”, but actually it was very well balanced, with heart. It really is a heart-led show, despite all of that stuff. For me, it’s about love – particularly the absence of love and how lives can get contorted and twisted with that absence. I don’t think I’ve seen a mystery or crime so clearly about love.

PT: I’m pleased you said that because as a writer it’s hard to bring a police drama and that emotion together. Absence of love became the beating heart and hopefully becomes something very moving at the end.

Ezelle Alblas

Bodies is released on Netflix on 19th October 2023.

Watch the trailer for Bodies here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS