Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider at Tate Modern

In 1909, a progressive group of artists in Munich formed Der Blau Reiter (the Blue Rider). Under the leadership of the Russian-born artist Wassily Kandinsky and his partner, the photographer and painter Gabriele Münter, the circle of friends came to play a prominent role in the evolution of modern art before the savage intervention of the Great War. The Tate Modern’s major new exhibition, Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, made possible thanks to a collaboration with Lenbachhaus, Munich has enabled this exciting work to be displayed in the UK for the first time since 1960.

Declaring themselves “a union of various countries to serve one purpose”, to create modern art, one finds the loosely affiliated band of co-collaborators that came to be known as the Blue Rider experimenting with bold colours and delving into sound and light. Over 130 works feature at Tate Modern. Aside from Kandinsky, other canonical figures like Franz Marc and Paul Klee appear on the walls here. Despite their presence, it becomes apparent the curator Natalia Sidlina is setting out to argue that women artists, notably Gabriele Münter played a crucial role in the movement. Münter herself is being elevated above Marc as Kandinsky’s chief fellow instigator. For ten years, after meeting in Munich following Kandinsky’s emigration from Russia in the 1890s, she and the Russian-born artist enjoyed a professional and personal partnership. Each manifestly influenced the other and they travelled together. Gabriele Münter’s innovative Tunisian photography and Marianne Werefkin’s powerful paintings challenge any notion that creative developments can solely be attributed to male artists within the movement.

From the opening room of the current exhibition, one finds works by Kandinsky and Münter alongside the avant-garde collective who in the main shared their subjective palettes, exploration of symbolically abstracted forms and engagement with emotional and spiritual concepts in the years leading up to World War I. The two totemic figures created a space for intellectual exchange where artists, writers, composers and performers could share ideas with academics and scientists. Marianne Werefkin’s piercing Self-Portrait of 1910 sees the behatted Russian aristocrat stare out of the canvas with demonically intense orange eyes, her features delineated by strokes of yellow before a tumultuous blue and green background. The relatively liberal and permissive atmosphere of Munich is testified to by Werefin’s 1909 tempera portrait of The Dancer, Alexander Sacharoff. Transgressing the sexualisation of the male gaze, the free-style performer is shown as Salome in a gender-fluid outfit. Elsewhere, Münter’s Listening (Portrait of Jawlensky) (1909) is a portrait of the artist – reduced to its essential forms – captured in a state of befuddlement at Kandinsky’s art theoretical chat. The Blue Rider’s diversity of influences is also drawn on by the Tate curatorial team with the inclusion of photographs from the Masterpieces of Muhammadan Art exhibition held in Munich in 1910.

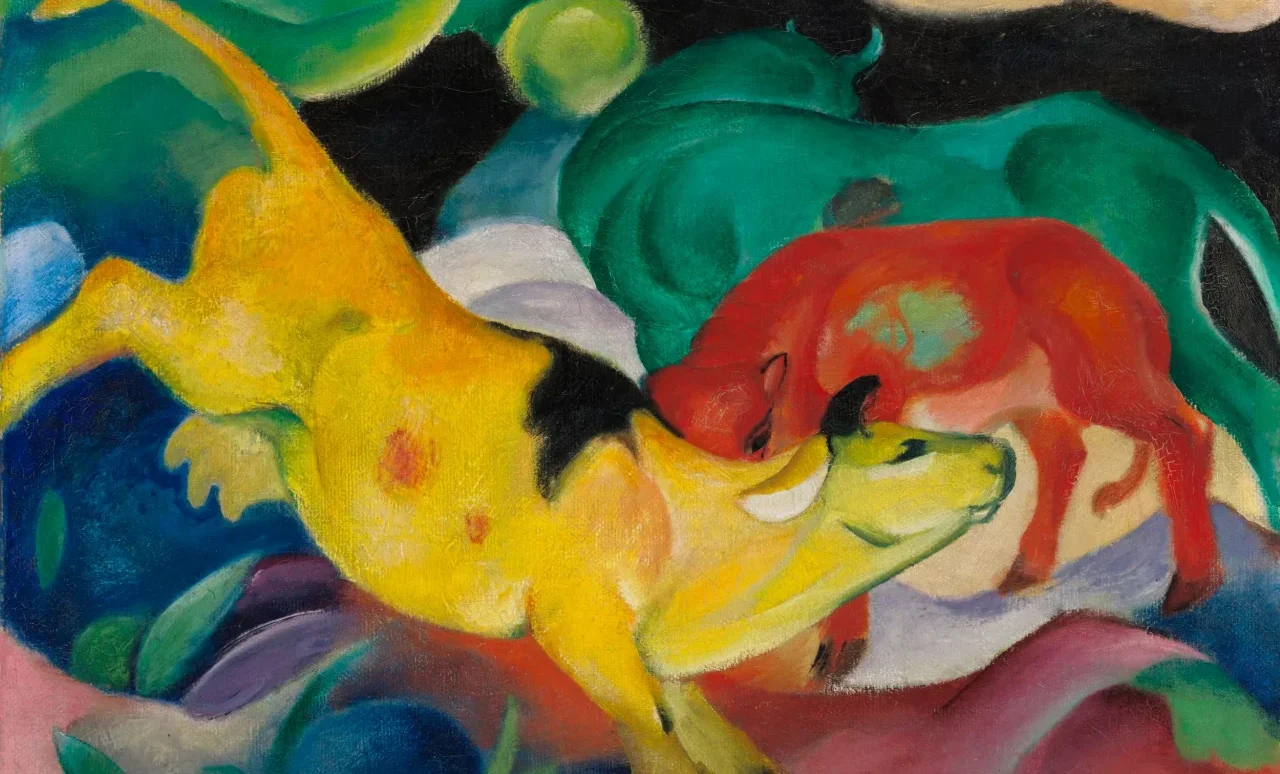

In 1909, Kandinsky and Münter moved from the bustling Bavarian state capital to the rustic idyll of Murnau, a small sub-Alpine town. This change of environment led the two to adopt expressive new painterly approaches whilst developing an interest in spirituality and folk art. A highlight at this point is Kandinsky’s The Cow (1910), with its bold play on colour, evoking a sun-drenched day in the countryside. The eponymous farm animal with poached egg yellow spots, in the act of being milked, seems to meld into the hill behind. Kandinsky’s All Saints and Deluge and Marta Franck-Marc’s figurative Three Kings have an unmistakable grounding in Christianity. One also discovers Franz Marc’s Tiger (1912) where the beast lies within a jungle composed of multi-coloured blocks and diamonds. The coiled geometry is intended to conjure up the tiger’s wild energy. Marc, later fated to tragically perish on the fields of Verdun in 1916, depicted a tiger due to his interests in Buddhism and Japanese prints. Gabriele Münter’s Kandinsky and Erma Bossi at the Table (1912) carries humour with a touch of feminist sarcasm. One finds Kandinsky, the artist’s partner apparently “mansplaining” some theory to another of their artistic circle, Erma Bossi. They sit in a rather feminine room, with Kandinsky sporting boyish Bavarian shorts in contrast to Bossi’s teacherly outfit.

Wassily Kandinsky wrote in his Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912) that, “The various arts are drawing together. They are finding in music the best teacher.” The Tate have one room here where music by the Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg provides the soundtrack for Kandinsky’s Impression III (Concert) of 1911, bringing into sharp focus the artist’s exploration of synaesthesia (a neurodiverse condition experienced by David Hockney) in which one sees synesthetic colours through music. Another “experiential environment” offers visitors a mounted camera-spectrum allowing them to contemplate Franz Marc’s Deer in Snow II (1911) and witness his use of the colour prism and colour theory.

Showcasing some captivating, and at other times unsettling, works of Expressionism, many rarely seen in the UK, this consistently exciting exhibition concludes with a room that reveals the artists cementing their legacy. The displayed Blaue Reiter Almanac (1912), including Kandinsky’s woodcut cover of St George, evidences the group’s concern for a range of art forms from the visual to theatre and music. There are letters fostering good relationships with collectors and galleries alongside exhibition curation. Although dispersed by the outbreak of World War, Der Blaue Reiter set the tone for transnational creative communities that continues to resonate for artists today.

James White

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider is at Tate Modern from 25th April until 20th October 2024. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS