Venice Biennale 2024: A guide to the ten best pavilions

Foreigners are everywhere: this is the intriguing assertion made by the curatorial theme behind this year’s Venice Biennale. Although it is as strange and overwhelming as ever, the 2024 edition marks a significant and applaudable shift beyond the traditional canon. There is a broad emphasis on art from the Global South, as both the central exhibition and many of the national pavilions set out to champion work produced by artists whose voices have too often been sidelined, such as those who identify as Indigenous, queer, disabled or immigrant. The result is a blend of unexpected perspectives that remind us of the many ways in which we are foreign, even to ourselves.

Some of the most interesting pavilions in the Arsenale, Giardini, and across Venice privilege diasporic experiences while also interweaving narratives around ecology, climate change and social justice. Across a range of media from video to painting to installation, there is a timely emphasis on anti-colonial resistance, often through feminist and/or Indigenous perspectives. And while viewers are encouraged to dwell on the horrors of a contemporary society built on legacies of colonialism and oppression, there are also myriad seeds of hope based on new perspectives and new ways of unpacking the past to build better futures.

What follows is a round-up of some of the most interesting pavilions on view at this year’s Biennale, including some of the big hitters and a few which have flown under the radar.

British Pavilion: John Akomfrah, Listening All Night to the Rain

The British Council’s pavilion has been transformed by John Akomfrah, well-known for his multi-screen video works exploring diasporic and black identity. A series of these unfold across the dimly lit rooms of the pavilion accompanied by immersive soundscapes that entice visitors to linger. Woven together like an audio-visual tapestry, powerful themes emerge surrounding immigrant experiences on British land, uprisings against colonial rule, and the relationship between military conflict and ecological devastation.

Iceland Pavilion: Hildigunnur Birgisdottir, That’s a Very Large Number

Icelandic Pavilion, Installation View, That’s a Very Large Number – A Commerzbau, Hildigunnur Birgisdottir, 2024. Photo: Ugo Carme

Probably this year’s most subtle pavilion, Hildigunnur Birgisdottir’s installation is nevertheless quietly thought-provoking. The Icelandic artist is interested in the strange relationships we form with mass-produced objects over the course of our lives. While many pavilions are oppressively dark, this one is bathed in natural light, revealing a sparse collection of doll’s plastic food enlarged to adult size, embedded in walls painted the familiar off-white of refrigerators and washing machines. The presentation is beautiful and perplexing in equal measure.

Benin Pavilion: Everything Precious Is Fragile

Benin’s debut at the Venice Biennale is a multifaceted exhibition bringing together works by Chloé Quenum, Moufouli Bello, Ishola Akpo and Romuald Hazoumè. The project offers a Beninese feminist take on the Yoruba notion of gèlèdè, a philosophy that embraces precarity. The pavilion champions Indigenous knowledge systems as a means of supporting and healing our fragile planet. Highlights include Hazoumè’s large dome built of anthropomorphic jerry cans and Bello’s dramatic portraits in tints of blue.

Singapore Pavilion: Robert Zhao Renhui, Seeing Forest

Installation view of ‘The Owl, The Travellers and The Cement Drain’ (2024) and ‘Trash Stratum’ (2024), as part of ‘Seeing Forest’ at the Singapore Pavilion at Biennale Arte 2024. Photo: Courtesy of Robert Zhao Renhui

Seeing Forest is an exploration of Singapore’s secondary forests – the wild spaces that spring up where primary forests have been cut down. These ecosystems are polluted and filled with non-native species but, as Robert Zhao Renhui’s video installations suggest, they are teeming with life. Much of one video work focuses on a plastic bin abandoned by migratory workers, which has become a refuge and lifeline for a range of wildlife, from frogs and insects to birds and mammals. The work suggests the resilience of the more-than-human world and the many lives lurking on our doorsteps.

Denmark Pavilion: Inuuteq Storch, Rise of the Sunken Sun

This year, the Danish pavilion has been entrusted to Inuuteq Storch, a photographer who weaves together a narrative of his homeland Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat in Greenlandic). The exhibition considers how Greenland is most frequently seen through the eyes of outsiders. Storch’s installations foreground not Greenland’s soaring cliffs or extraordinary glaciers, but rather his close friends and family going about their everyday lives. These are the individuals, Storch subtly reminds us, who feel the most severe effects both of climate change and marginalisation.

Australia Pavilion: Archie Moore, Kith and Kin

Archie Moore, kith and kin, 2024, Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti. © The artist. Photo: Courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

Archie Moore’s installation Kith and Kin was the worthy winner of this year’s Golden Lion (the top prize bestowed by the Venice Biennale judges). Moore spent two months hand-drawing an enormous, meticulously researched family tree onto the walls and ceiling of the space, documenting 65,000 Aboriginal lives. In places, the text is smudged or erased, nodding to the many ways in which Aboriginal people have been forgotten, omitted or obliterated from the record.

Austria Pavilion: Anna Jermolaewa, Swan Lake

Anna Jermolaewa & Oksana Serheieva, Rehearsal for Swan Lake, 2024, Installation view, Austrian Pavilion, Biennale Arte 2024. Photo: Markus Krottendorfer and Bildrecht

For the Austrian Pavilion, artist Anna Jermolaewa has drawn on her experiences of feeling the USSR as a refugee in 1989. The show centres on a film of three women in a ballet rehearsal, sometimes accompanied by a live performance by Ukrainian choreographer Oksana Serheieva. The piece alludes to how during times of political unrest, Soviet television replaced their regular broadcasts with Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake in a loop for days. In Jermolaewa’s take on the theme, however, the dancers are rehearsing for a change of regime in Russia.

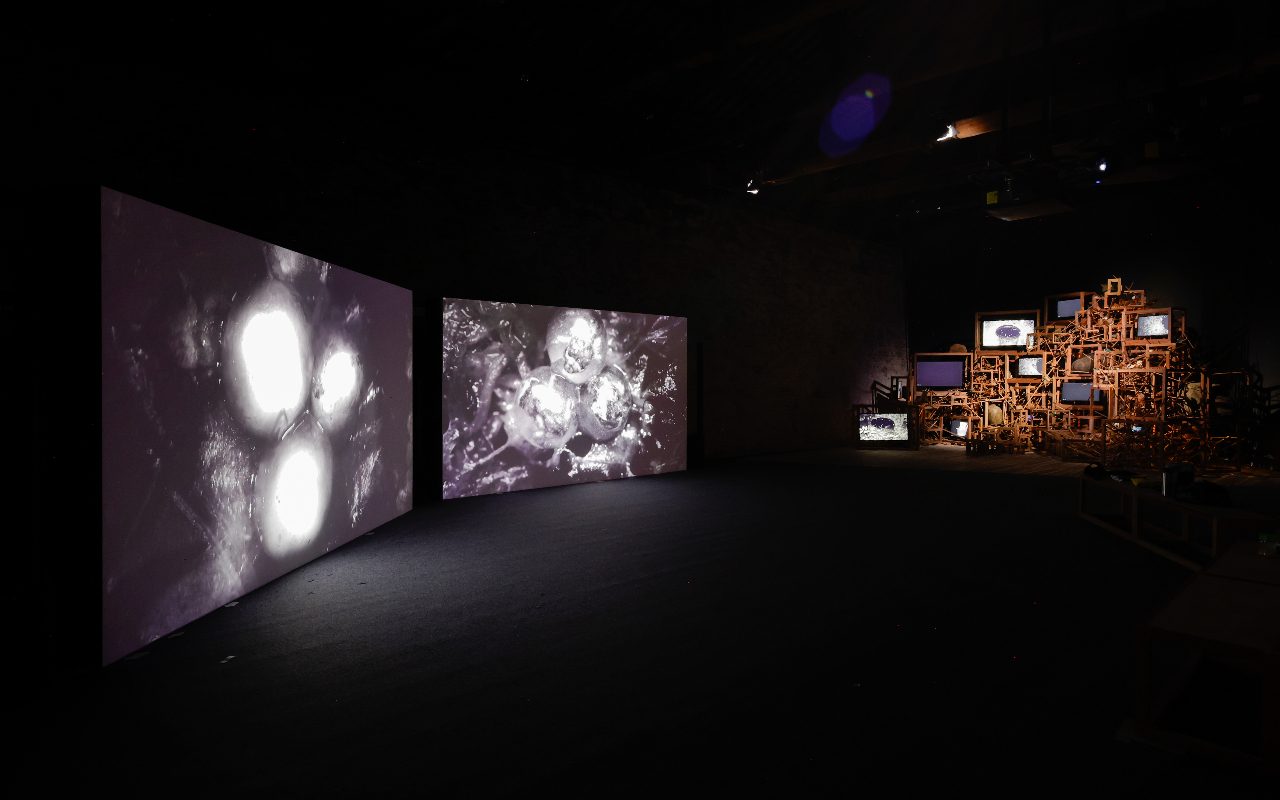

Lithuania Pavilion: Pakui Hardware & Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, Inflammation

Set within the beautiful Venetian church of Sant’ Antonin, away from the main Arsenale and Giardini sites, the Lithuanian pavilion presents a collaboration between artists of two different generations, both exploring the theme of inflammation. The installation combines sculptural and painted elements to create an immersive setting that evokes sickness of mind, body and environment. The show offers a convincing prompt for viewers to consider both bodies and ecologies as fundamentally interlinked systems.

France Pavilion: Julien Creuzet, Attila Cataract Your Source at the Feet of the Green Peaks Will End Up in the Great Sea Blue Abyss Where We Drowned in the Tidal Tears of the Moon

Unlike many of the rather dark and serious pavilions at the Biennale, Julien Creuzet’s installation is upbeat and uplifting. Objects and materials dangle enticingly from a latticed structure on the ceiling, simultaneously complementing and obstructing video pieces, all to a loud soundtrack of dance music. Like its title, the show is both poetic and expansive, taking water as a theme to connect apparently disparate geographical settings including the Caribbean, France and Venice, exploring diasporic experiences in a playful, human way.

Lebanon Pavilion: Mounira Al Solh, A Dance with Her Myth

Pavilion of Lebanon at la Biennale Arte 2024. Courtesy of the Artist & Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg. Photo: Federico Vespignani ©️ LVAA

Mounira Al Solh’s installation for the Lebanese pavilion combines drawings, paintings, sculptures, embroideries and video. The artist looks to mythology surrounding the Phoenicians, the ancient civilisation that lived in what is today Lebanon. In particular, the work focuses on the myth of Europa, the Phoenician princess carried off by the god Zeus who took on the form of a white bull. Through her documentary and poetic visual language, Al Solh attempts to “rescue” Europa from her fate, crowding the space with witnesses in the form of evocative masks.

Anna Souter

Photos: Courtesy of La Biennale

For further information visit the Biennale website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS