Silk Roads at British Museum

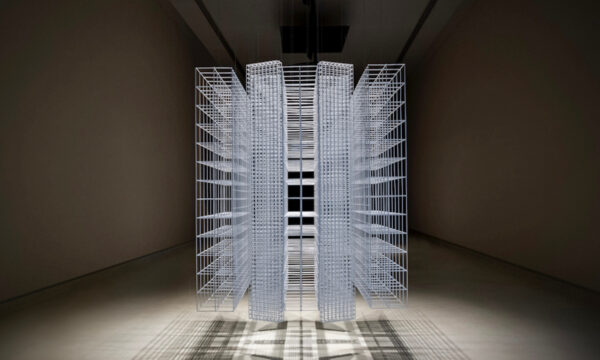

Since its coinage by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877, the Silk Road has captivated the romantic imagination. It is often romanticised as a mystical corridor where explorers like Marco Polo journeyed through deserts, mountains and ancient cities, and where merchants followed a golden path of wealth and opulence or idealised as a symbol of peaceful cultural exchange, where knowledge, religion and art flowed freely between East and West. The use of the plural Silk Roads in the British Museum’s new exhibition is a clear indication, even before you step foot into the Sainsbury’s Exhibitions Gallery, that the collection is ready to challenge the historical tendency to confine the overlapping networks and storied histories into a single, linear narrative.

Organised into five geographic zones, stretching broadly from East to West, the display is flanked by cinematic backdrops of expansive desert landscapes and vast murals that evoke the perilous journeys of ancient travellers, but it is above all else about the people who lived and traded along these routes in antiquity.

“This exhibition is the British Museum’s first collaboration between three curators from different departments and specialities,” notes Luk Ping-yu, the Basil Gray Curator of Chinese Paintings, Prints and Central Asian collections. Her acknowledgement of its multi-curatorial approach is not lost on observers, as the 300 objects – from the oldest chess pieces ever discovered to a six-meter-long wall painting from Uzbekistan’s Hall of the Ambassadors – are arranged into an exceptionally cohesive picture that transcends individual fields and traditional domains.

Silk Roads’ interdisciplinary approach perfectly reflects the multi-faceted and intersecting stories that unfolded along the paths. Visitors are invited to immerse themselves in the scent of balsam, a blended oil so tightly controlled that the penalty for smuggling it past customs was death, as well as discover the story of Willbald, the English monk who successfully sneaked this precious oil past Umayyad custom officials.

Visually similar objects from opposing sides of the same trade – such as iron neck restraints used to bind captives sold along the Eastern trade routes and fine silver neck rings crafted from melted dirhams for the wives of Rus traders who profited from this slave trade – are displayed together to reveal the complex and intertwined stories woven into the fabric of the Silk Roads.

Christina Yang

Photos: Courtesy of British Museum

Silk Roads is at from 26th September 2024 until 23rd February 2025. For further information or to book visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS