My Everything

“I wanted a normal child! Normal! I’m ashamed!” It’s an ugly sentiment for the parent of a child with intellectual disabilities to espouse. Mona (Laure Calamy, who between this and Full Time has cornered the market on harried single mothers), finds herself shouting it at the top of her lungs come the end of a hellaciously stressful week. Her adult son Joel (Charles Peccia Galletto) lives with her, but has found some measure of personal autonomy. He works, for one, and somewhat less conveniently for Mona, his place of work has led to romance with co-worker Oceane (Julie Froger), who is also disabled. Their coupling has led to a pregnancy, an impending new reality that has Mona baffled to see the young couple so much more confident in the future than herself. As she fends off the attacks of Oceane’s overprotective father and navigates a new relationship, all the personal resentments accumulated over the years of Joel’s care come bubbling to the surface.

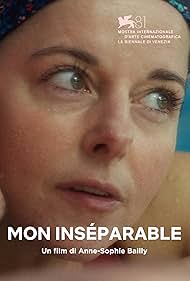

There’s a perceptive, intimate familial drama to be found in Anne-Sophie Bailly’s feature debut. In moments, My Everything is able to grant equal care both to the easy-going intimacies and frustrations of this mother-son duo. We see that Mona loves her son, but Bailly also frees her to behave unflatteringly, even off-puttingly. It can be challenging to retain sympathy when she lambasts her soft-spoken son for his dependency, and then again for making what he insists was a considered adult decision within a considered adult relationship. Still, perhaps the onus needn’t be on the audience to love everything about the people onscreen, not when simply appreciating their honestly flawed humanity is so much more important than judgment.

Why, then, does My Everything still leave a sour taste in the mouth? Joel clearly has more autonomous possession of his life than even his mother is wholly prepared to accept, while still having needs that challenge his ability to exist alone. There is a richer, more balanced version of this very film in which his perspective is prioritised to the same extent – perhaps even more – than his mother’s. There are still so few films that centre the experiences of the differently abled, and even fewer that cater to their perspective. It’s sad, then, that come a legitimately shocking turn of events around the midway point, Bailly’s movie has fully aligned itself with a storied tradition of narratives that emphasise the burden placed upon long-suffering carers, at the expense of those in need of care. “What a terrible sacrifice this woman has been forced to make,” the feature seems to say, but we are tempted towards a counterpoint: “What must it have been like for Joel to grow up with a mother who only seems to love him on occasion?”

Whether intentionally or not, My Everything seems to assert that the strain of caring for a disabled child is so great that the occasional act of wilful neglect, bordering on abuse, may be necessary for the letting off of steam. Those in positions of care are only human, and which of us hasn’t thought things we regret, even gone so far as to speak them aloud? For this sturdily well-acted drama to align itself so thoroughly with these misgivings, however, exposes an ugliness at the core of things.

For a parent in Mona’s position, to re-compose oneself, keep calm and carry on is one thing. To actually empathise, is another.

Thomas Messner

Read more reviews from our London Film Festival coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the London Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS