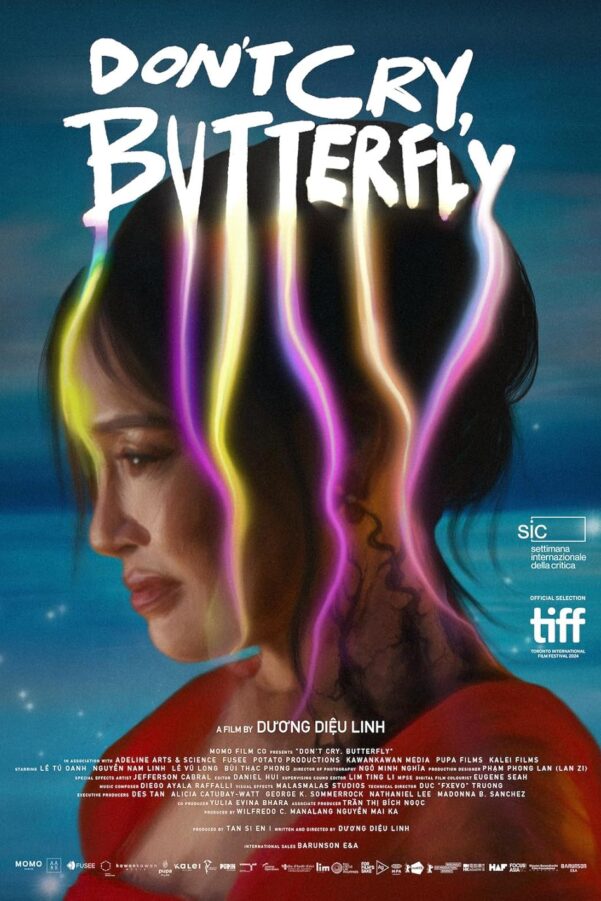

Don’t Cry, Butterfly

As Duong Dieu Linh’s feature debut begins, the first spectre on hand is not supernatural in nature at all. His adultery exposed, the Hanoi-based housewife Tam (Tu Oanh)’s husband has not been banished from the flat to which much of the film is claustrophobically confined. Instead, he shuffles through the space as an eerily wordless presence; a ghost haunting a dead marriage. For her part, Tam is something of a spectral presence too, shuffling in a daze from one meticulously arranged wedding ceremony to another, her professional life cruelly compounding the indignity of her private one. That is, if it could be called private when a litany of neighbours stop by to offer counsel and gossip, their Greek chorus promptly joined by voices from the internet. At every turn, Tam is advised on how she may reverse her family’s misfortune, largely through means of self-improvement. “If your husband is unfaithful”, the world seems to say, “best to look in the mirror to know why, and then to amend it.” All the while, a nigh-on sentient batch of mould encroaches on the narrow living space. A bleakly matter-of-fact melding of a familial slice of life with a literal haunting, Linh’s feature marks a striking – if punishing – calling card.

In its stark evocation of urban isolation, especially within a codependent familial space, Don’t Cry, Butterfly feels as profoundly lonely and despairing as Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse. The sense of souls stewing in denial, insecurity and desperation is conveyed with such acuity that the result can occasionally lapse into the inert, but moments of deadpan observational humour grant the film a droll heartbeat. When Tam is found standing just that little bit too close to the edge of a bridge, a panicked trio of police officers defeatedly asks “What’s with this bridge-jumping trend?”, citing the quota of prevented suicides they are obligated to meet. Instead of lightening the load, the moment’s casual absurdity only further nullifies any sense of hope or warmth. What we are watching is a mundane horror-comedy of errors.

If there is any warmth to be found in Don’t Cry, Butterfly, it is mainly with Tam’s teenage daughter, who harbours dreams of escape from the despond around her, seemingly oblivious to the evil presence encroaching on her parents’ apartment. For most of its running time, the familial dysfunction only hovers on the edge of the supernatural, never wholly tipping over. Come its dreamlike close, the balance changes, but the resounding sense of sorrow is much the same. Linh’s film is too suffocatingly airless to describe as enjoyable, or even wholly engaging on a moment-to-moment basis, but it troubles the mind long after it disperses, leaving a tremor of disquiet in its wake.

Thomas Messner

Don’t Cry, Butterfly does not have a release date yet.

Read more reviews from our London Film Festival coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the London Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS