“The play doesn’t try to patronise you with simple answers to massive global problems; it’s about the discussion and the journey”: Gabriel Howell and Joshua Malina on What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank

A provocative and explosive play, Nathan Englander’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank is currently running at Marylebone Theatre. Full of tears, laughter, alcohol and drugs, the story of the night follows two families – an extremely conservative Orthodox Jewish couple from Israel and two liberal Jews and their son Trevor with an affinity for equal rights and tackling the climate crisis. What starts as a reunion between two best friends who haven’t seen each other in decades leads to hard conversations on politics, the conflict in Israel and Gaza, traditional Jewish values, moral high ground and human rights. But more than just a lesson in political extremes and divide in religious beliefs, Englander’s script is a profound exploration of family, friendship and identity. What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank is a fun and chaotic marvel that leaves audience members breathless with laughter and speechless in topics to ponder.

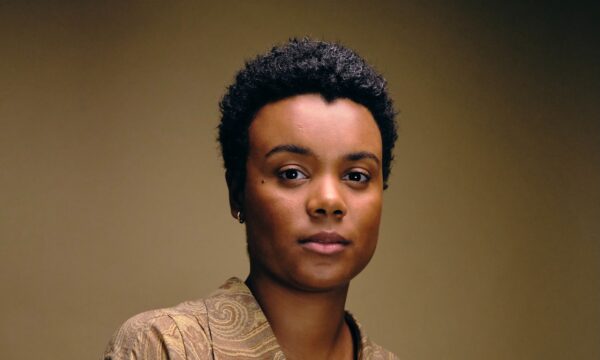

The production boasts the brilliant writing of Englander with direction from Tony-winning director Patrick Marber. It stars The Big Bang Theory’s Joshua Malina, theatre veterans Caroline Catz, Simon Yadoo, Dorothea Myer-Bennett, and actor on the rise Gabriel Howell who will be featured in the live-action remake of the beloved animation franchise How to Train Your Dragon as Snotlout. The Upcoming caught up with Malina and Howell, discussing issues and themes in the play, the importance of divided conversation and active listening, collaborating with Englander and what they hope audiences can take away from the performance.

Let’s start off with a brief introduction to the play What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank and the characters that you play.

Joshua Malina: The play – in a nutshell – is about two Jewish families; two Jewish couples with one being a very religious couple and the other a secular couple with their son. The wives have known each other for years; they grew up going to Orthodox school, Yeshiva, and haven’t seen each other in 20 years. We get together for a long night of discussion, tears, fighting and laughter. It’s a little bit of a Jewish culture clash but I think it’ll appeal to anybody who has a family. You don’t need to be Jewish – it explores themes and issues surrounding family, faith, relationships, marriages, parents and kids. I play Phil who is the dad of the secular couple. Caroline Catz plays my wife, and Gabriel Howell plays my son. Phil is a successful lawyer in Miami, Florida in the States. He’s funny and cutting – sometimes too cutting, sometimes too funny at the wrong moments – and he’s very confident in his opinions which will be challenged over and over, over the course of the night.

Gabriel Howell: I play Trevor, the son of Phil and Debbie. He’s sort of the emcee of the night. He’ll bring you in, talk to you throughout and introduce the scenes. It’s almost like his little playdate, the way it’s sculpted. I’m bringing in these adults and I’m letting them fight it out and then I’ll come on and throw bits and pieces in. Trevor feels like a few miles away from the argument of the two couples. I think he feels that there’s this big generation gap. The arguments that the two couples get caught up in, Trevor is often frustrated that the conversation is leading anywhere except where his heart lies which is the environment, sustainability, equal rights, and people being in a level playing field. I think he feels a bit frustrated and not listened to. It’s a bit of a Chicken Little type character that I’m saying, “The sky is falling!” and no one’s listening to me.

Were either of you familiar with Nathan Englander’s work or had you read his original short story before coming into this project?

GH: I didn’t know of Nathan before this. When I got the script and I read the story, I was just astonished by his [writing]. He writes so beautifully that even the prose, you want to speak it out loud. So, for that to be adapted into script form just feels like such a natural progression. It’s such a pleasure to say his thoughts out loud; I love hearing him talk, I love hearing the reading of his writing. There’s something about the way he puts words right next to each other that really gets to your heart immediately – it sort of bypasses your brain. I adore Nathan’s writing, but I was unfamiliar with it [at the start]. But I’m very glad I’m familiar with it now! I hope that that’s the case for the mass amount of the audience. That they’ll come and they’ll be subsided and swept by his writing [which] I think is gorgeous.

JM: I was a huge fan of Nathan. I did a previous iteration of his play. It’s a very different version that we performed in 2022. The inciting moment in what happened on October 7th and the things that have happened in the months and almost a year since have been rewritten massively to take place in present-day. But we did [this play] in 2022 and I’d been very lucky in my career occasionally [in that] I’d have something just magically land in my agent’s email saying, “We have a play by Nathan Englander that they’re hoping you’ll do in San Deigo California.” I was like, “He’s like, one of my favourite writers!” I had read the collection of which this play is the title of the story, I read the beautiful novella called kaddish.com, a great novel called Dinner at the Centre of the Earth, another collection of his called For the Relief of Unbearable Urges. It was coming from one of my favourite novelists and when I read it – although I never met him before and I didn’t know him – it felt like a bespoke role that has been created for me. It was two years of frustration as the pandemic hit and we kept having to postpone the play. We eventually did it and I told Nathan at the time, “If I could just sign a contract that I’ll only play Phil for the rest of my career, I’d do it in a second.” Actually getting to revisit the material and in a new, expanded, deeper, more profound, funnier version is an unbelievable treat.

Mentioning the previous version of this play, how did you audition or take on the role for this iteration, Josh?

JM: I really weaselled my way in. I was already in on the ground floor having been in it before, and then it was another one of those lucky moments [where] I got to do Tom Stoppard’s play Leopoldstadt, which is very, very different to this play but it shared some sort of thematic DNA. I got to be friends and enjoyed working with Patrick Marber who won a Tony for directing it, and there’s some debate about whether he asked me to see the play or I offered it. I believe I said to him, “You’ve got to read this play,” and he did read the play. As I anticipated, he really connected with the material then met Nathan and really connected with Nathan. They rewrote, and rewrote together, developing and making this play. That was my in. I was like, “I kind of made this happen so now you’ve got to cast me!”

How about you, Gabriel, how did you audition for this play?

GH: Well, it came to me – and it’s such a similar thing to what Joshua said about something that just landed on your desk – and I read it and it’s just one of those things where you sit down and you read it and the next time you blink, you just finished. There was no analysis in the first time reading. Sometimes you’re like, “Is this good? Should I do it?” But [this one] immediately landed and it just reads so swiftly and so beautifully, then I was at the end. I remember texting my agent and I was like, “I think I might have to do this.” It was that sort of thing of like, “Oh, I really want this one,” you know what I mean? Normally, you can save your heart sometimes if you don’t get it. But it was one of those ones where I have to do this. Josh was already signed on, Patrick was already signed on, and I’ve been a fan of Josh for years, and years, and years.

JM: That’s my boy!

GH: I’ve told him so many times that I just copy him when cultivating my career. To get the chance to work with him and be in a room with him was just an absolute no-brainer. To be his son – it’s really great! The trick to being a good actor is to be playing a good actor’s children. This is my advice for young actors: you want your parents in a play or a film to be really good and then it’s easy.

JM: And I watched Gabriel’s performance which is fantastic and a huge breath of fresh air when you’ve seen all these older people yapping about what they think and then getting an entirely new perspective that represents a whole generation of other people. I notice in the physicality of him little things of like, “I do that!” He’s a very observant actor! I even found something that I know that I kind of nicked from my dad and I see Gabriel doing.

The premise of this play lies within the idea of two very different ends of a political and religious spectrum coming together for one night. At a time when political debate is becoming quite polarising and binary, how important do you think it is to have these very nuanced discussions and touching on extremely difficult subjects within an art form that’s lighthearted, funny and engaging?

JM: I will say that one of the most beautiful things about the play is that first and foremost, it’s not about any specific political thing. It’s not about Israel and Gaza – although there are discussions of the issues surrounding that. It’s a play about family, relationships and real people. It’s deeply human and universal. But I also think there’s great value in the discussions that are difficult to have that most people don’t have. A lot of people have retreated to very monolithic, dug-in positions – and I’m sure I’m guilty of this at times too – where you just yell and restate your position to the other side without any kind of other interactions. These people are going to spend whatever it is – five, six, seven hours – together, and they are forced to find common points. Of course, whether or not they end up agreeing or having changed their minds or forced to listen to other people’s narratives and points of view, I think if the audience walks away feeling like they’ve been in a discussion that they haven’t been in a long time, or maybe even compelled to have discussions with people whom they may disagree with, then I think Nathan was really onto something.

GH: Nathan said something really interesting in the first week [that] we’re in a really weird time at the moment where people have stopped talking about things as things are getting more and more extreme. I think “retreating” is [a really nice way to describe it] because there’s an isolation and everyone’s sort of retreated backwards instead of coming forwards to buttheads. I think there’s nothing wrong with butting heads. I think we have to start butting heads about things out loud in the same room to get anywhere on anything ever. It’s an act of love to give someone the time of day to disagree with them. To just write someone off is actually a bigger insult. Watching the play as I do, watching the arguments come up and out of people, I can only see that as trying to make things better. Because if you write it off, it won’t ever go anywhere, and I think that’s a little bit of what’s happening with social media, echo chambers and buzzwords. Just the retreating back concept is very well-said by Josh. [This play] is about stepping forwards and butting heads.

JM: Patrick did a beautiful job directing the play, and he gave us a sort of revelatory note, really only a few days ago – four weeks into the rehearsal – where he felt like we, playing our characters, we’re writing off the other characters too quickly sometimes just in the facial expressions. He said, “Remember, you’ve got to actively listen and consider what the people are saying.”

And in the play, Trevor plays this role of mediating the situation between the four adults in the room. Is that a similar situation that occurs in real life for you Gabriel when you’re having discussions and you find yourself caught mediating as well for the older adults surrounding you?

GH: No. They’re all fiercely intelligent and I’m intimidated by all of them. I stay quiet and every now and then I quip. But it does feel like I’ve been deemed the youth monitor or something. Any sort of reference to pop culture, social media, slang, brands and anything technology-wise. There have been times when there was a reference to Instagram in the play and everyone looks swiftly to me and then I have to step up. That’s where I shine. It’s a really intelligent room – it’s brilliant! People’s work and people’s artistry around the work; I’d love to say that I would mediate around the room but I’m sort of just trying to catch up with everyone.

JM: And I will say, Patrick has a disarming way of – you never know when it’s going to happen – in the middle of rehearsing a scene, he’ll ask the question, and he goes around the room, “Well, what do you think of this?” We had – not just backstage but in our free time and breaks – deeper discussions and we’ve interacted during rehearsals in a deep way. The play is very provocative and it has provoked us to [have] interesting discussions.

Gabriel, you mention talking about pop culture within the play and people looking to you for advice on implementing that dialogue. Does that change the script within the actual play in any way?

GH: Because it’s such a current play, it’s literally set on the day we’re going to do it every day. It’s like the play changes every day. Not massively, but it keeps up with the world as it is moving. We all sat around on the first week and we all went through it pretty much line by line to ensure it was as current and as sharp as it could possibly be. Obviously, Nathan and Patrick had to take the lead on that, but it was really thrown to everyone as the best line wins. There were certain character beats or certain terms of phrase, which were slightly shifted, changed and fine-tuned to make the play as liquid as it could be. It’s really just tightening it up.

JM: Nathan – I’ve never met a writer who’s less precious about his own material who will rewrite, and rewrite and rewrite, and take in [feedback]. My approach to acting is always you’re given a script, and my personal inclination is not to give an input on, “My character wouldn’t say this,” because that is what my character would say, that’s my job. It’s nice and amazing to meet someone who’s as collaborative as Nathan. Somebody who wants to hear your take and is always willing to go in and do work. The screenwriting is tremendous.

GH: And something so beautiful about his work is it’s so front-footed and there’s something – specifically with Trevor and his appropriate obsessions with climate change and the oncoming disaster – so everchanging that we’re even several steps behind where we should be on the climate disaster. Nathan was really honest with me earlier on where there’s like a few references to New York turning orange when it did. He said, “That’s already gone, that’s already past tense.” You know, we’re moving so quickly, so rapidly, and we’re in a state of real emergency that he even was like, “We’re going to take those references out because sadly and devastatingly, by the time we get to it happening onstage, there’s going to be another natural disaster that’s happening.” And it has – there are the storms in Florida where this play is set. There’s something so real [about that] and it’s like a shot of espresso as an actor to just be like, “Right, tune-in dude! What you’re saying is happening, you’re not disappearing from the world for an hour and a half, you’re opening the window to it.” I think that’s a beautiful metaphorical shove from Nathan to tune in and stay tuned in, and the day-to-day of it is why this play is important. Not just switch off from it.

JM: My probably naïve hope is somehow, there has to be a rewrite with some good news in it, with steps towards peace rather than having references to greater-standing conflict. It would be nice if sometime between now and then that there’s something positive and some progress.

GH: I’ve got so used to the changes being awful changes. Every time, every edit has been darker because of the reality. So, that’s a really beautiful thing to say.

Just building on the collaboration with Nathan on the script and the overall direction of the play, Josh earlier on you mentioned having weaselled your way into this particular adaptation and wanting to play Phil for the rest of your life. Did you ever have any suggestions to Nathan and Patrick when they were brainstorming for this play? Was there any directions you wanted them to take when it came to crafting Phil’s character?

JM: I would say not much. They were very kind and they included me a lot. Every time there was a new draft, they would send it to me and they asked me for my responses. I was thrilled and felt privileged because, again, my natural inclination is I’m an actor and a cog in the art machine. I’m very comfortable with that and I feel like whatever I’m sent with in the end is whatever I put forward. They tell me what the character is. It has been a delight to have been invited into the process, but I would say I’m always reminding myself not to overstep. With Patrick directing and Nathan as an amazing writer, I largely keep to the acting.

And when people finally see this play for the first time, what do you hope they take away from it? What kind of message do you want to leave them with?

GH: The play says so much and is so thorough that it just gives it all to you. It doesn’t try to patronise you with simple answers to massive global problems. It’s about the discussion and the journey being the thing. As humans, we always get a little bit end-goal-orientated and what’s the quick fix to making things better. I think, personally, that’s leading us towards a dead end. With Nathan’s play, it sprawls it all out there in a sort of cathartic, tangled, chaotic mess that actually, in doing so, is hopeful. Not because the argument might stop but because the act of the argument itself is hopeful. I hope that gives a little bit – and it has for me – the audience a lot to churn on, a lot to think about and ultimately, a little bit of momentum to keep on.

JM: I completely agree with Gabriel. I will say, in one way, I’d set the bar low. I want people to leave and say, “Oh, I enjoyed that. I laughed, I felt something, I felt that those were human characters.” It’s not a message play but if people walk out feeling they want to dig into any issues and ideas that the play raises, that would’ve been a huge success. I want to make sure that people know that it isn’t a play with an agenda. There’s no simple, easy, tidy walking out of the play going, “Oh, here’s the message of the play.”

Joshua, this is your London stage debut. What took you so long to get here and will we be seeing any more of you in the future in the West End?

JM: I would love that. It took me this long because nobody offered me anything. I don’t often say “no” to things so had someone offered me a play in London earlier, I’m sure I would’ve done it. It’s a bucket list item for me. I would be delighted if this led to other opportunities for the play, and I’d also be thrilled if I could do this play elsewhere in the afterlife of the play. To be doing theatre with a cast that I love and with the creatives that I respect and love is an absolute bucket list.

Gabriel, just to briefly talk about How to Train Your Dragon’s live-action film, tell us about the experience filming in Northern Ireland and how excited are you for people to see what you and the rest of the cast have done with such a beloved franchise.

GH: I love Belfast – it’s the first time I’ve been. It’s a gorgeous, gorgeous place and I love the crew from Belfast as well. I loved it! I’m a huge fan as well, and the huge thing about that job for me is I would have gone and seen it anyway. I would be there on opening night, in the cinema crying at the score, the romantic flight,and all these moments. When I got the chance to be a part of it, it was like a bonus. It wasn’t like, I got the part and, “Oh, now I care!” I cared. I really cared! It’s an element similar to Nathan with Dean that as the creator, if these remakes are going to happen, I don’t want it to be in anyone else’s hand but Dean’s, you know? It was just a beautiful heart-filled experience. It was a dream come true and it was amazing.

Mae Trumata

Image: Mark Senior

What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank is at Marylebone Theatre from 4th October until 23rd November 2024. For further information or to book visit the theatre’s website here.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank is at Marylebone Theatre from 4th October until 23rd November 2024. For further information or to book visit the theatre’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS