The Monuments Men press conference: Cast explore the history of their films

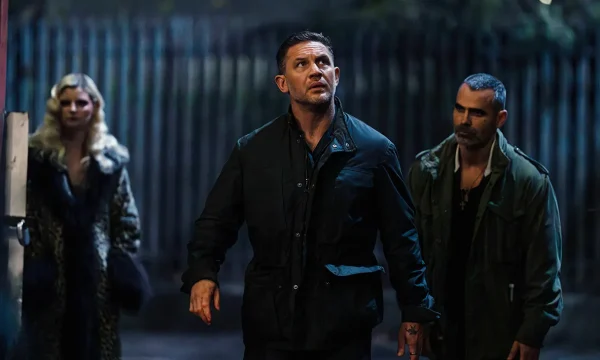

Packed with a stellar ensemble cast, dropping names like George Clooney and Bill Murray, The Monuments Men is the story of the greatest heist in all of history. In London tonight for the premiere to release their new film, The Upcoming caught up with director, writer – and starring actor – George Clooney, co-writer and producer Grant Heslov, with the lead cast of Matt Damon, Bill Murray, John Goodman, Jean Dujardin, Bob Balaban, Dimitri Leonidas, as well one of the surviving Monuments Men, Harry Ettlinger.

The morning started with a brief introduction from Robert M Edsel, renowned author of The Monuments Men novel. He began in discussing the avarice of the Nazi regime, and in particular that of Hermann Göring, the man in charge of procuring the artifacts for Hitler’s private collection. After a brief art history lesson, he shone a spotlight on the Monuments Men, and shared his process of writing his novel, from meeting these famous men and women – adamantly emphasising that women indeed played a pivotal role – to how he wanted to tell the story and reach the widest possible audience that he could.

After a brief interlude, the cast were welcomed by applause and the proceedings began:

In the film, Frank said “art is to be held up and admired”. Given our location [the National Gallery], is there a particular piece of art that you admire?

GH: Michelangelo’s David

JG: Starry Night, Van Gogh.

BM: There’s a wonderful photograph of Mariano Rivera one day at a baseball game, where all the players wore the number 42, and he was the last person to wear the number 42, and when he went for the pitching change, there were about seven men on the mound with number 42.

They share a brief joke as Damon interrupts with: “baseball’s huge over here [in the UK].”

GC: The ones that sort of take your breath away, I don’t think I’ve been more moved than when walking in to see the sculpture at the Legilux Memorial.

MD: Yesterday we got to see Da Vinci’s Last Supper.

BB: I’m going for a more contemporary art form. There is an artist named Philip Guston, and he has a giant foot that I admire.

DL: It’s a building. I saw the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. The story that really amazed me was that people worked on it and passed away, and then their sons would work on it and pass away, but none of them would see it finished because they’d been making it for over 200 years, and generations of families had worked on this building.

JD: I like Kaminski for his balance, and (lilting) The Mona Lisa.

Earlier on [in Edsel’s introduction], it was said that you all made the decision to change the names of the men. What was the reason for that, and what did it allow you to do dramatically with the film?

GC: We wanted to change the names – obviously. Some of the names are pretty recognisable. The man Jean’s character was based on – he was a hero for the French. We wanted to be able to tell a story – much like most films do – and we didn’t want to give any of these real men any flaws that would make anybody upset, like their families. You could have a small drinking problem, or a little bit of a flirtation with a certain curator (hinting to Damon’s character). We just wanted to be able to tell a story without offending anyone.

The film captures a great camaraderie, and a sense of humour and team spirit. Was it important that it existed off set as well as on?

MD: It was fun to work with these guys together. We all got to play around with each other. Wait – that sounded wrong.

GC: Yeah, we’re all friends, and we all get along. It was a really wonderful time. We didn’t lose sight of the idea that we were talking about very important issues along the way. Everybody knew – we all took proper care.

MD: George actually had to work. He wrote the script, produced the movie and directed as well as starred in it. The rest of us were used to headlining movies and carrying them, so when you get into an ensemble like this, where you’re working two days a week, it’s really fun. We were working a really great movie with a great director, and he (George) had it under control – we laughed a lot.

GC: You were the only one working two days a week.

JG: The spirit of everyone was interesting. Everyone was very respectful to each other. We appreciated each other, and I was very grateful to be cast in this film. George did such careful preparation, and it made each day easier – and more fun.

A lot of war films are intense, or seen as overbearing. Did you approach the film from a comedic perspective, or was that something that appeared during writing the script or filming?

GH: We always knew that we wanted to have humour in this piece. George and I were watching a lot of war films from our youth, and a lot of them had callous humour, and dealt with the situation through humour. We deal with life through humour, so we always knew that we wanted to have some funny tone to it. We were dealing with a subject that was very serious in its nature, so there was a real balancing act – and that was the fun part. Making the piece, it was fun to strike that balance and that tone. And then we cast all these guys, and they bought a new level of humour to it that we didn’t write.

Did you undergo basic training or was it more you all having a bit of a laugh together?

GC: I think John should take this one.

JG: Definitely… with a knife and fork.

BM: I had some basic training too. Mine involved learning that, for women, putting tight pants on involved lying on your back.

JG: Can I just say that we couldn’t have done this film as easily as we did without the expert knowledge of Jill Hobbs. I worked with him several times before. We lost him around Christmas time, so I’d just like to pay tribute to Jill Hobbs.

Bob, having been directed by the likes of Steven Spielberg, could you say a few words about Mr Clooney’s skill behind the camera?

BB: He’s one of the best directors I’ve ever worked with – that’s the serious part. The other part is that he makes it such great fun. Good work happens when somebody knows what they’re doing, and he makes it easy because he’s been an actor for a few months… He knows that you have to be relaxed and happy in the work environment – and it works.

What is like to be directed by somebody who is your friend?

MD: It’s actually much easier to be directed by a friend. When you’re working on a film with somebody who’s a friend of yours, it removes all the diplomacy. There’s a whole way of how you’re supposed to speak to each other on film sets, and its all about protecting peoples egos, and their feelings. But when you’re working with your friend, they can just say: “that sucked”. There’s a baseline of trust that never comes into question, and it helps to solve problems a lot quicker. Its more fun – and more efficient.

Jean, what was it like to work on a film like this after working on The Artist?

JD: (Translated) It was a pleasure – it is a pleasure. For me, it was very different. It was a pleasure to be there with everybody, of course, and to have my scenes with John (Goodman). What I like about being with John is that we don’t bother each other. He has his silences, and I’m the louder of the two. I have this feeling that we start to act before we start filming. He’s always very respectful. (In English) I love him.

Were there any pranks on set?

GC: Matt came to me at the start of filming and told me he wanted to lose a few pounds, which he should never have told me. So, over a period of a month and a half, he went back to LA every few weeks, and every time he’d go away, I’d ask the costume department to take in his uniform half an inch.

One of the questions the film asks is what the world would be like without art and creativity. Can you imagine your life without creativity, or if there was a specific moment you you can pinpoint in your life where art really has mattered or made a difference for you?

BM: Back when I started acting in Chicago, I wasn’t very good. I remember my first experience onstage – I was so bad I walked out. I walked for a couple hours, and then I realised I had walked in the wrong direction, not just in relation to where I lived, but in a desire to stay alive. So I thought, “if I’m gonna die where I am, I may as well do it over by the lake. Maybe I’ll float for a while – after I’m dead. So I walked over to the lake and realised I’d hit Michigan, and I knew Michigan avenue ran north too, so I started walking again. I ended up at the Art Insitute in Chicago and went I inside, not feeling like I had a place to be there. They used to ask for a donation, y’know, when you walk into a museum, but I walked right through – because I was ready to die. I walked in, and there was this painting there – I don’t even remember who painted it – called The Song of the Lark. It’s a woman working in a field, and there’s a sunrise behind her. I’ve always loved this painting, and I saw it that day and just thought, “there’s a girl with a whole lot of prospects, but the sun is coming up anyway, and she’s got another chance.” I think that gave me some feeling of security, knowing that I had another chance.

GC: I was going to tell the same story, but…

JD: I agree with Bill.

Hannah Ross

Photo: Chanel de Yong

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS