Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979 at Tate Britain

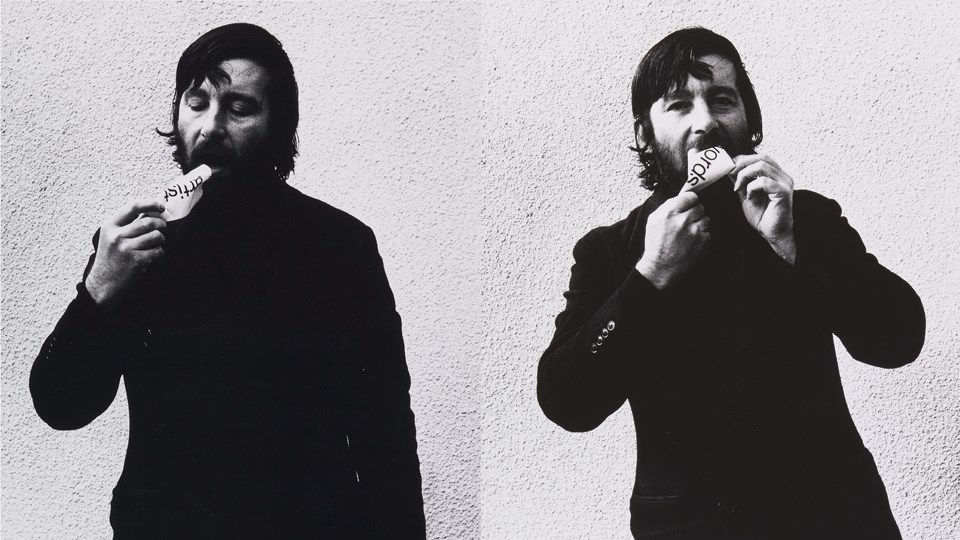

At first glance, many of the works in Tate Britain’s Conceptual Art show mean very little: a pile of sand, oranges, a glass of water on a shelf, pages of art theory pasted to the wall. Most honest viewers will admit that, even after extended viewing, many remain opaque. This is part of the exhibition’s strength, but it is also its weakness.

The works of art on show are meant to be challenging, made by artists who wanted to shake up the definitions of art that had been firmly cemented by Modernism by the 1960s. The show tries to demonstrate how conceptual art evolved in Britain as a discrete movement. It also tries to distinguish this movement from what most people unthinkingly talk about as “conceptual art”, ie any artwork whose meaning comes from the idea behind it, rather than its materiality or figurative content.

This is a valid point, and the exhibition certainly makes for a comprehensive walk-through of conceptual art in Britain in this era. It also makes a good attempt at explaining why many of these artworks were made and how they express their meanings. If you’re one of those people who is flummoxed by apparently impenetrable artworks, this show might help you to a better understanding.

One of the particularly bizarre highlights of the display is An Oak Tree by Michael Craig-Martin. The piece consists of a glass of water placed on a high shelf, along with a fictitious interview with the artist. Craig-Martin explains that he has turned this glass of water into an oak tree. He has done this, he claims, without changing the outward appearance or properties of the glass. Nonetheless, because he says it is an oak tree, that is what the viewer must accept it as. Craig-Martin is trying to get the viewer to start questioning art again (both his own and others’), and to question the ways in which we view and value artworks, and his intention is admirable.

However, this is not an easy concept to get one’s head around, and it is just one difficult idea in a whole show of difficult ideas. The effect soon becomes overwhelming, and the viewer starts wondering why we give credence to any of these (undeniably wacky) concepts and constructs. Many of the works are text-based, as this is a key part of the development of conceptual art, but the presence of 270 individual works from the Tate’s archives presented side-by-side makes them difficult to take in. Similarly, there is very little colour in the exhibition apart from a large pyramid of real oranges in the first room, and the monochrome affords little relief to the eye or the intellect.

The exhibition is a valiant attempt to explain conceptual art, but for the average viewer it will probably fall short. Both the artworks on show and their curatorial explanations seem to raise more questions than they answer, and leave the viewer wanting less rather than more.

Anna Souter

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979 is at Tate Britain from 12th April until 29th August 2016, for further information visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS