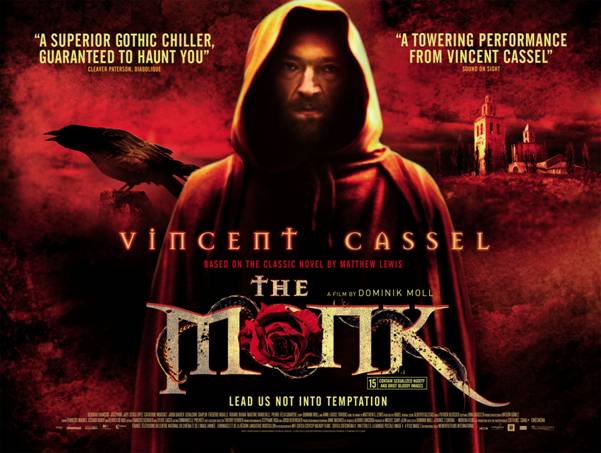

Interview: Dominik Moll reveals his inspiration behind The Monk

Critically acclaimed director of Lemming (2005) and With A Friend Like Harry (2000), Dominik Moll in gripping and suspenseful thrillers. In his latest film, The Monk (Le Moine), starring Vincent Cassel, Moll constructs a gothic world of restraint and passion, of good and evil.

The Upcoming chatted with him about his own passions and inspirations and this highly anticipated feature The Monk, which will be released Friday 27thApril.

How did you come across Matthew Lewis’ novel The Monk (1796)?

I knew of the novel but I only read it about five years ago. Actually, a friend of mine said, “Look there’s this book that I really love, why has it never been made into a film?” I’d been meaning to read it for quite some time anyway. I like gothic literature, I mean, I’m not a specialist but novels that explore the darker side of the human soul are always interesting.

So I read it. It wasn’t obvious to me it should be made into a film but it stuck in my mind. I mean, I really enjoyed reading it but I thought, ooh err, it’s a bit complicated! But yes, the book’s images stuck in my mind and kept coming back and coming up. So I said, oh, maybe there is something to it. And so I read it again. I think the first reason I was attracted to it was the idea of a very formal pleasure, because it’s so visual, it allows to play around with gothic elements. You know: ghosts, devils, graveyards, nuns, monks, incantations… And so I started to think about it more closely. Part of this formal pleasure is because The Monk is a very anti-Catholic novel, which Matthew Lewis wrote to denounce the hypocrisy of Catholicism. The characters are a bit caricatural, of course he wants them to be very exaggerated. In the novel, Ambrosia comes across as a hypocrite whose faith is not true. But I wasn’t interested in that. It took me some time to find something more appealing as a story and bring greater depth to those characters.

The novel is so rich that it could be turned into ten different films and all completely different from one another. For example, Luis Buñuel wrote an adaptation, which was directed as comical and farcical… One could make a pure horror film from it, or a porno, or whatever! Everything is possible!

What I also found interesting was really the tragic love story, which plays almost like a Greek tragedy, between Ambrosio and Antonia. So I think, at first it was the idea of a formal pleasure, of something very cinematic. But then, little by little by working on it, this idea of developing the tragic love story aspect.

You work very closely on your scripts and screenplays. Have you always been a part of that process?

Well, I do most of the writing. In France it’s just the nouvelle vague; you don’t really have the choice. There aren’t many screenwriters, so there aren’t many screenplays on the market. And so, it has become a tradition that directors write their own screenplays, sometimes with co-writers. It feels there’s a real lack of screenwriters but I’m sure the screenwriters that write only screenplays will feel that it’s difficult in France because directors write their own screenplays! I’d be very happy to come across a screenplay already written, that’s ready to be filmed. But of course you have to find the right connection to the screenplay to feel that you can develop it as a project.

What fascinated you about the psychology of a monk character, like Ambrosio’s?

Well, for me, he’s not a hypocrite; he’s someone who grew up with religion, someone who’s never known anything else because he was abandoned as a child. He grew up in a monastery and that’s all he knows. So he tries to fill his life with that but of course there’s always a void within him, having never known his family. I think someone who doesn’t know his family’s love will probably have a slightly harder time becoming a well-balanced person… I would say that’s basic psychology, for beginners! But Ambrosio succeeded in constructing himself with religion and he tries to do it very sincerely.

However he also has never been in a situation where he has to deal with his emotions and compulsions because they have always been repressed by religion. He becomes quite helpless because he is confronted with something he has never known.

I think that is the danger of religion, or even political ideology, when it takes all the space in your life, and there is no room for anything else. In that respect, the film says that religion can be dangerous if it’s the only thing that exists in your life, but there are many ways one can interpret it. Antonia’s mother and Valerio are very bitter about religion but Antonia has a quite well-balanced relation to it. She takes it as something positive that helps her to live, but it’s not something exclusive.

Vincent Cassel has an incredible screen presence. How did you enjoy directing him?

Oh, it was a treat to work with him! When I met him and we talked about the part, he was immediately interested and he felt that it was something different from what he was used to doing. I wanted to work with him in a way where his acting would be very much restrained, and he was very curious to explore that too. So we really trusted each other, and it was a very constructive collaboration.

The actress who played Antonia was just 15 when we shot the film. Vincent was very good at making her feel at ease; he didn’t play the international star who could crush a young actress. He’s very generous in that respect.

Joséphine Japy’s performance was very mature for a 15 year old.

Yeah, that’s what I really like about her performance. I wanted the actress to be the same age as the character. It was important that she should bring that youth and that innocence, and then at the same time she should have the intellectual maturity that Antonio also has. I was very happy when I found her because she had this perfect balance between youth and maturity.

It seems your films are interested in their protagonists’ loss of control. What interests you about this theme?

Yes, I think that’s true. Each time the main character is trying to be too controlling of his life, in thinking that he can control things at all, he doesn’t really know how to react anymore. For example, Ambrosio with his religious beliefs, and also in Lemming, and Harry (With a Friend Like Harry), suddenly, when somebody from outside of their world comes in and shakes their full mental construction, they are a bit helpless and everything crumbles apart. I do think there is a danger in being too controlling of things.

You obviously understand the language of thrillers. What excites you about directing them and what do you hope the audience takes from them?

What I like in thrillers, or in my kind of thrillers, is to explore what is on the surface and what is underneath the surface. Especially with human beings, most of us have quite normal appearances and I think most of us are probably mad potentially! It just doesn’t show too much… It just crops up once in a while! I think that we all feel a potentially frightening thing within us, a desire to kill somebody, or whatever it may be. Thank God most of us don’t do it! But somehow, it’s there. And so to play with that in a film, making people identify with a character whose compulsions suddenly get unleashed and they are no longer in control, can be frightening for the audience. It can also be quite liberating, because at least somebody is doing something that we would want to do!

Which is something Hitchcock did incredibly. How much influence has Hitchcock been to you?

Hitchcock is one of my major influences and my favourite filmmaker.

To what effect do you enjoy using surrealism? Something obviously important in Hitchcock films also, there are a few dream sequences in The Monk. How important did you feel surrealism was to tell this story?

I’ve been always interested in surrealism. The surrealists were always interested in dreams, and film and dreams have a lot of things in common. When I make films, I am more interested in creating worlds that do not exist, rather than trying to re-create a naturalistic reality. Although, there are a lot of films that are naturalistic and realistic that I like a lot, as far as I’m concerned I am more attracted by making artificial worlds, like Hitchcock and many others.

I think it’s no accident that the surrealists really loved the novel The Monk, which they re-discovered in 1920s France, because it is not realistic, and because it has a very dream-like quality. I’m not so interested in portraying heavy surrealism in films, because then it becomes an experimental film, and you don’t know with whom to identify. But I do like to see what happens when surreal or strange elements intrude into everyday life, and start shifting the focus so that you don’t know really what is real or unreal, what is in your mind or in reality. This borderline between mental things and real things is something that I find quite fascinating to explore with film.

Thank you Dominik Moll!

Sophie-Jeanette Burton

Read our review here and watch a clip of The Monk here

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS